Today’s issue is about the sky-high world of airspace rights.

Here at Alts, we like to explore some pretty wild markets. Islands and Hot Wheels have been some of my favorite topics to explore.

But air rights is a really interesting topic — one I’ve been wanting to do for some time.

Note: This is Part 1 in our series on air rights. If you enjoyed this, here’s Part 2.

Let’s go 🛫

Table of Contents

Urban airspace is getting crowded

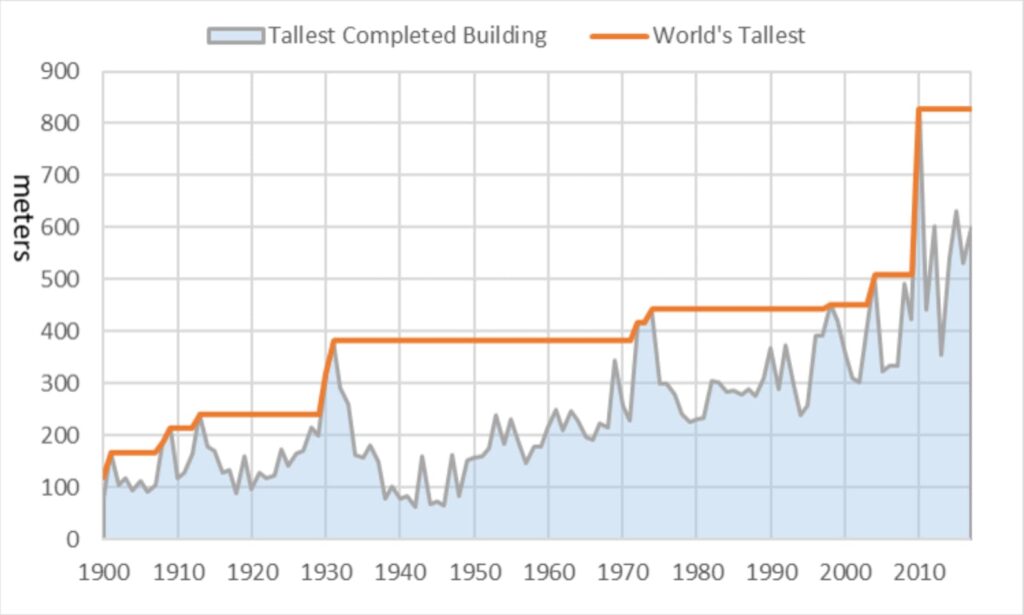

Back in the 1950s, there were just 160 skyscrapers — half of which were in New York City. The average height was 570 feet, or a measly 45 stories tall.

Fast forward 70 years, and boy, have times changed. 106 new skyscrapers were built in 2020 alone, and the average height of a new tower has now doubled to 1,300 feet.

But there was a problem.

The spaces directly above, below and adjacent to skyscrapers were getting extremely crowded. Citizens and governments became concerned. Even developers realized that building on top of this massive infrastructure had become a tall order (sorry).

With that, the concept of air rights was born.

What are air rights?

Air rights are the legal right to construct (or prevent construction on) the vertical air space directly above a plot of real estate.

This is a new concept. 100 years ago, it didn’t exist. In fact, ancient law from the Romans dictated:Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos.

This translates to, “Whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell.”

Basically, if you owned property, you could build as high above it (or as low beneath it) as you pleased.

The history of air rights

Like skyscrapers themselves, the history of air rights stems from New York City.

In the early 1900s, skyscrapers were popping up just as commercial air travel was taking off. As NYC’s skyline became taller, the aviation industry knew society needed a way to prevent crashes and flight delays.

In 1919, a Paris convention introduced laws to ensure private real estate became publicly owned after it reached a certain height. While this served the public interest, it wasn’t really an investment opportunity until the 1950s.

Railroads were the first to grasp the potential of commercializing air rights. One of the earliest instances was the Grand Central Terminal, one of New York City’s busiest transit hubs and most iconic buildings.

Grand Central’s lead engineer William Wilgus designed and built a platform above the rail tracks, which allowed developers to construct properties above the railway.

This gave a much-needed income boost for railway operators, who were struggling with building costs and new air rights taxes. Wilgus referred to their strategy as ‘taking wealth from the air.’

The strategy continued to evolve until 1954 when an 800-foot high skyscraper was proposed to replace the Grand Central Terminal. This would’ve been a huge coup for Wilgus and his team, but the public wasn’t loving it.

Protests prevented Grand Central Terminal’s demolition, and eventually, the towering structure was built behind the station. Originally called the Pan Am building, it is now known as the MetLife building.

Air rights markets

In many cities, the total buildable airspace is capped by the government through a complex set of zoning laws. Since each building owns the vertical space directly above them, owners have the right to build up to the authorized limit set by the city.

But not all building owners want to exercise this right! Owners can decide not to build on the extra space they’re entitled to, and instead sell those rights to other building owners and developers.

Because of this, entirely new air rights markets have been created out of thin air. Unbuilt airspace can now be bought, sold, and traded like anything else.

Furthermore, rights can be combined to reach a desired height. For example, say a developer wants to build a Supertall skyscraper. They may need 1,000 feet of vertical space, but only hold the rights to 500 feet. A nearby church probably has no desire to build a tower, so they can