ISAs and human capital contracts

This week we’re continuing our Ethics & Assets series with a look at investing in humans. We’ll explore a few companies making noise in this space and flesh out the signal.

It sounds sketchy, but as you’ll see, the actual controversy here is pretty minimal. The bigger questions are around the viability of these businesses, and the optics.

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

A short history of investing in people

Okay, this is bold, but here’s my attempt to boil 5,000+ of years of investing in people into a few bullets:

- Slave management. If we’re being honest, slavery is the original “investing in people.” For thousands of years, slaves have been bought and sold like commodities. The reward is food, shelter, and clothing. No money, obviously.

- Serf management. Servitude goes back to the Middle Ages. Basically slavery, but sometimes you’d get a little cash.

- Contract labor. Contracting pre-dates full-time paid employment. Bound contracts go back to before the industrial revolution when mercantilists offered farmers & artisans incentives to accelerate exports.

- Adam Smith. During the American Revolution, Smith points out that training workers can add economic value and benefit society. These crazy ideas about self-interest and the division of labor put the nail in mercantilism’s coffin.

- The Industrial Revolution moved humans from farms into factories, and basically led to the system we have today.

After the Industrial Revolution ended and labor unions grew, human resources emerged as workers demanded a higher quality of life, and robber barons realized it was probably in their best interest if employees didn’t die in horrific workplace accidents.

Over time, investing in people simply meant hiring, training, and rewarding employees. It also meant providing flexibility to allow for personal growth and work/life balance.

Personnel management didn’t really kick into high gear until Ford Motor Company introduced the (then unheard of) 8-hour work day.

Human capital theory

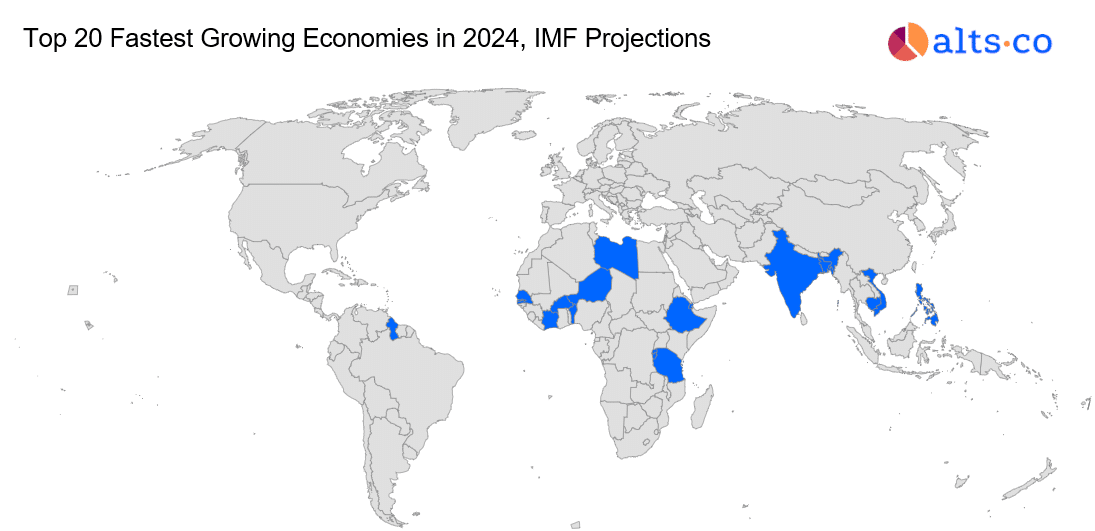

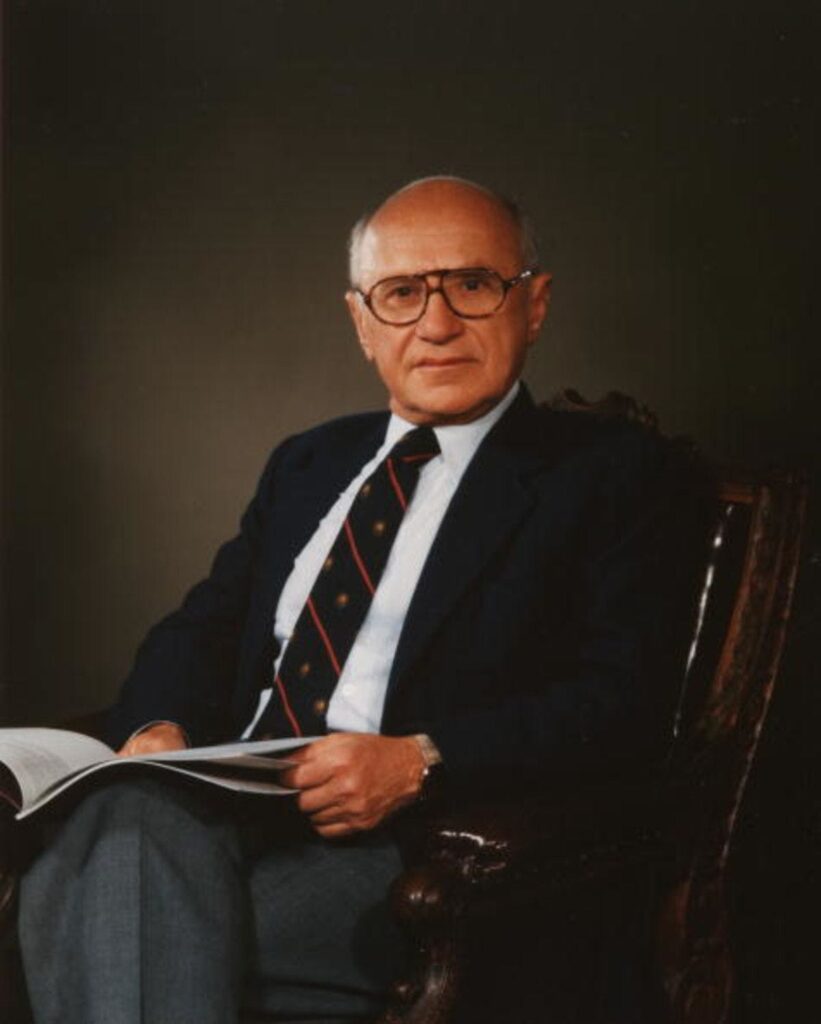

Fast-forward to 1960, and a private meeting between Teddy Schultz and Milton Friedman from The University of Chicago School of Economics, a birthplace of modern libertarian economic ideas.

Friedman was originally against the idea of companies investing in people. He felt it didn’t make sense for a firm to fund employee training schemes, since that person might one day literally walk out the door and join a rival company.

He proposed a new form of human capital; one which recognized the power of investing in people (and even recognized that the ROI on human capital was higher than the return on physical).

But he added an enormous caveat. In his 1945 doctoral dissertation co-authored with Simon Kuznets, Friedman said that if a person has an investment made in them, whether public or private, they should be expected to pay it back.

Human capital also played a critical role during the Cold War. Reagan and Thatcher weaponized human capital rhetoric against the Soviet Union with a free-market ideology proclaiming that all people are capitalists.

Laborers have become capitalists not from [ownership of stocks] but from the acquisition of knowledge and skill that have economic value. – Theodore W. Schulz

During the 1980s, with the help of the political-industrial complex, Friedman’s human capital theory spread through universities, foundations, and institutions. It was framed as nothing less than a battle of capitalism vs. communism; of good vs. evil. And it worked.

But most interestingly, in his dissertation, Friedman included a small annotation suggesting that someone could “sell shares” of their future income to finance their training & education.

Two decades later, Congress passed the Higher Education Act, and America’s federal student loan program was born.

Modern human capital contracts

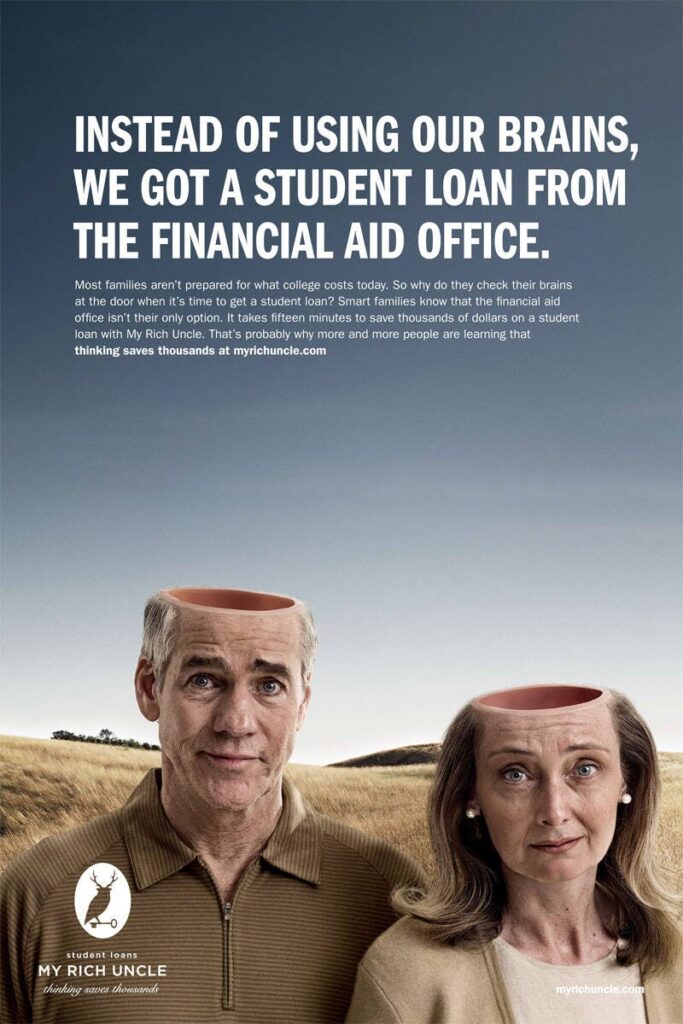

Modern-day human capital contracts are traced to a company called My Rich Uncle.

In 2000 college costs were rising, and private financing was surging. Founders Raza Khan and Vishal Garg were inspired by Friedman’s human capital theory, and sought to quantify the earning potential of college students based on their academic achievements and career prospects.

The idea was simple: Students who couldn’t access traditional college financing (due to poor credit) could use their future earnings as collateral. Investors could then purchase an economic share of a student’s future income stream.

But what’s interesting is that while MRU began with a Friedman-esque idea to sell shares of a student’s future earnings, it rapidly devolved into little more than a massive subprime lender.

MRU was one of the first companies to use algorithms to determine loan terms, and saw a huge market in financing loans for students with little or no credit history. It quickly became one of America’s largest private student loan companies, originating $550 million in student loans in just seven years, and competing with heavyweights like Sallie Mae and JP Morgan Chase.

They initially earned a good reputation and went public on the NASDAQ in a $200m IPO. But they went bankrupt during the 2008 financial crisis once lending requirements got strict.

Income Share Agreements (ISAs)

What are ISAs?

An ISA is a financing agreement where a student receives money upfront to spend on education. In exchange, the lender receives a fixed percentage of the student’s future income when they get a job.

ISAs are typically associated with higher education loans (though presumably they could be used for anything.)

How do ISAs work?

An ISA provider determines the repayment terms for each student based on characteristics like college major and projected salary.

Details:

- Credit agnostic. ISAs are not based on a student’s credit score, but future earning potential.

- Interest-free payments. ISA agreements only kick in when the student earns over a certain amount of money per year

- Salary floor refers to the amount a graduate is expected to make upon graduation.

- Income repayments vary between 2% and 20%. So if a graduate earns $100k/year, they pay back between $2k – $20k per year until the payment cap is hit.

- Payment cap is the most a student has to pay. Typically, payment caps don’t go above 2x of the borrowed amount.

- Repayment terms typically range from two years to 10 years.=

- Riskless for students. The ISA provider takes all the risk. If the student never earns money, the agreement never kicks in.

While considered a novel idea in America, ISAs are nothing new. As I wrote on LinkedIn, Australia’s higher education finance system (known as HECS) is one of the world’s most successful examples of ISAs. Almost every single Australian Uni student uses HECS. It’s basically an ISA program for the entire country, funded by the government.

In America, the most famous example of ISAs in action is the coding bootcamp Lambda School, (now called Bloom Institute of Technology after they lost a naming lawsuit.) Instead of paying for classes upfront, Bloom students don’t pay a dime until they get a job paying at least $50,000/year. Once they get hired, Lambda takes 17% of their earnings, until a payment cap of $30,000 is hit.

The Unincorporated Man

If all this talk of selling future earnings to the highest bidder seems a bit like a dystopian sci-fi novel, that’s because it is.

The 2009 sci-fi novel, The Unincorporated Man envisions a world 300 years in the future, where every human is “incorporated” at birth. All humans start with a personal portfolio, with a fixed supply of 100,000 shares.

The shares are split up so that the government takes 5%, parents own 20%, and children retain 75%. But as kids grow up, they find it necessary to sell most of their shares to get ahead. And as they do this, they lose control of their lives. Corporations make career and life choices for them. People end up living the rest of their lives buying back their shares so they can one day attain freedom.

The book is a bit cheesy, but the parallels to today are obvious. As a society, we’ve decided debt is the key to freedom. People are coerced into debt at a relatively young age, working for years to repay huge student loans they may not have needed to begin with. It can really feel like they’ve lost control of their lives.

Startups and human capital contracts

Surprisingly little has been written about My Rich Uncle’s early pivot from creator of human capital contracts to a run-of-the-mill loan provider; which is too bad, because similar many other companies have attempted similar business models.

Pave

Pave started as a crowdfunding platform for accredited investors in 2012 to invest in people’s passions. You could invest in a martial artist or filmmaker and get a portion of future earnings. The site also offered a compelling social aspect to investing, by encouraging mentorship between “backers” and “prospects.”

But Pave pivoted from this crowdfunding model because it wasn’t profitable. Co-founder Oren Bass took the company and rebranded in 2019 into a compensation management platform. The company helps companies plan and communicate wages with a trove of compensation data. In 2020, Pave raised $16 million from a16z.

Upstart

Upstart started in 2012 as another crowdfunding platform with an Income Share Agreement. But by 2014, Upstart also moved into the personal loan business, marketing its services as a simple, flexible loan marketplace.

Upstart is still around today as a consumer lending company. They market themselves as an “AI lending platform” that partners with banks to provide consumer loans using non-traditional variables, such as education and employment, to predict creditworthiness. (Sound familiar to MRU?)

Ultimately, both Pave and Upstart found it difficult to get traction with the idea of buying shares of people. (Sensing a pattern here)

It didn’t help that their services were limited to accredited investors, who mostly shied away from an unproven industry lacking federal regulation.

But now, with interest rates rising, these companies have new problems to deal with..

Upstart’s loan delinquencies are starting to rise, and the stock has fallen by 94%.

Human IPO

Human IPO is the latest buzzy startup to attempt a proof of concept for human capital contracts.

Despite the suggestive name, the company doesn’t actually let anyone invest directly in a human being for a slice of their future income. All Human IPO does is allow people to buy a portion of somebody’s time.

For example, right now for $10,000 you can buy 30 minutes of Pelé’s time. You get a 1-on-1 video call with the soccer legend. Scientists, sports agents, social media influencers, and entrepreneurs are all selling what are effectively expensive consulting sessions. It’s essentially Upwork for celebrities.

So why call it Human “IPO“?

Like with other public investment markets, the price (hourly rate) changes based on demand, and that time itself can be traded. If your time is in-demand, your price goes up. If you think someone’s time is undervalued, you can buy it on the open market. As an investor, you’re making a bet that the purchased hours will be worth more in the future (whether it’s utilized by you or someone else.)

It’s not a bad idea at all! But the company’s name/branding came off as tone-deaf, and clearly struck a nerve. Human IPO launched the week of Juneteenth — amid BLM protests and racial tensions — and branded itself as “a marketplace for investing in people.” Yikes.

Some called it “modern wage slavery,” and questioned the underwriting process. Others berated the company for propagating a new form of indentured servitude.

I was asked to chime in and was quoted in Wired:

There are ideas that sound great on paper but are terrible in reality. I think this has the opposite problem. It’s not necessarily a terrible idea, but the branding and optics are horrific.

I stand by my quote. It’s basically a consulting marketplace with an unnecessarily controversial name.

Stride

Stride’s “outcomes-based alternatives” (ISAs) have come under fire for potentially using biased algorithms when deciding a student’s interest rate on loans; systematically overcharging students who attend historically black colleges.

According to Investopedia:

Data revealed that students who attended historically Black colleges and universities paid more for a Stride Funding ISA product than students from comparable non-HBCU colleges did. For example, a computer science major attending Tuskegee University, an HBCU, was quoted $2,802 higher for a $10,000 ISA than an Auburn University student with the same major. The study found similar disparities among students who attend other minority-serving institutions (MSIs), such as Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs).

To be fair, Stride wasn’t given an opportunity to respond to the report by the Student Borrower Protection Center (SBPC). But we also haven’t seen a rebuttal to SBPC’s evidence.

Avenify (now part of Edly)

Avenify sought to become a third-party marketplace lending platform for Income Sharing Agreements (ISAs). The idea was that borrowers (students) would use the platform to find investors willing to fund their human capital contracts, and vice-versa. Intending to tackle the student debt crisis, in 2020 they raised $330k on Republic.

However, by 2021 the company had essentially turned into an affiliate loan comparison site for nursing students. Earlier this year, it was announced they were acquired by Edly for an undisclosed amount.

Defynance

Defynance is the company behind the ISA Credit Fund, an alternative fixed income investment fund backed by ISAs.

This is a Reg D fund. Despite the name, they have nothing to do with decentralized finance (though that would be interesting too!)

Lumni

Lumni is an ISA platform targeting Latin America. They’ve been busy buying up other ISA platforms, including Paytronage.

Align

Align claims to be the only company in the United States to offer Income Share Agreements for general use.

Closing thoughts

Milton Friedman inspired a generation of libertarians to conceive of ways that humans could sell shares of themselves.

Yet, 70 years later, these ideas have mostly devolved into a handful of failed/failing subprime loan providers, and a slew of ISA platforms fighting for “college education deal flow.”

I don’t know why the idea of human capital contracts keeps falling flat. Perhaps the idea simply rubs people the wrong way. These companies should be careful with how they market themselves. Nobody wants the dystopia envisioned in The Unincorporated Man.

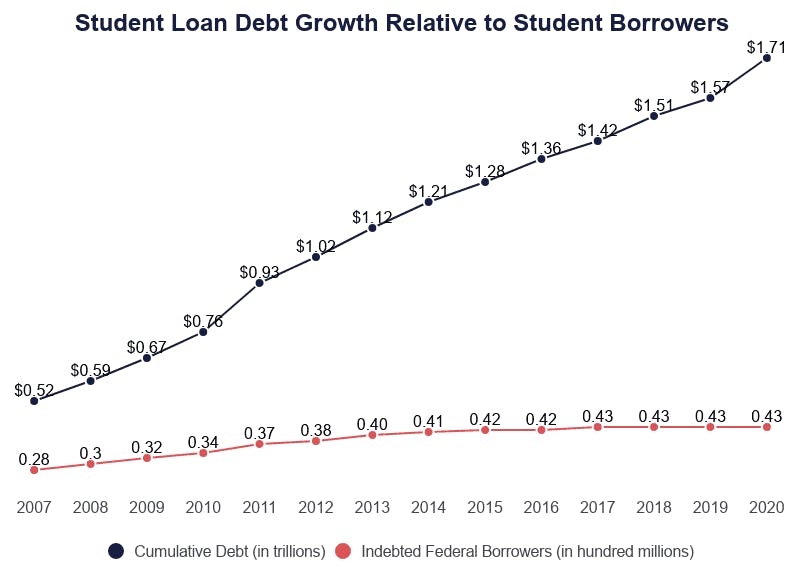

What I do know is that America’s student loan system is severely broken. (And we didn’t even get into the issue of loan forgiveness!) ISAs seem like a happy medium between free market libertarian utopia and unregulated dystopian servitude. They represent a new way of thinking about higher education. A whole new protocol for how things could, and arguably should work in the US.

I think the US can learn a lot from Australia here. The system works pretty darn well and I’d love to see the US government offer ISAs to every American college student someday.

But a system like this seems like it’s decades away at best. In the meantime, the US government’s sluggishness & failure to fix education finance is an opportunity for private companies to step up.

The existing solutions may not be perfect, and they may not be for everyone. But you gotta start somewhere.