Today is The Oscars (otherwise known as that thing people used to care about.) But while Oscar viewership is down, our love for films is eternal.

So this week I’m adding another part to our film financing series. We’ll look at how movies & broadway shows get off the ground, and explore the landscape for alternative investors.

Note: This is Part 2 in our film financing series. You can read Part 1 on film financing and crypto here.

Take a short break from the Silicon Valley Bank noise and explore 👇

Table of Contents

Big budget film studios

Film financing lives across two totally separate worlds: Big budget, and indie films.

At the high end, filmmaking is all about safe bets.

Neither studios nor investors want to take risks anymore. This has led to boring, predictable superhero movies that usually do pretty well financially (especially internationally).

It’s frustrating as hell to everyone from movie lovers to Martin Scorsese, who famously said Marvel movies aren’t really movies.” But economically it makes sense.

Think of it like venture investing. A repeat founder with a history of successful billion-dollar exits will have a far easier time getting funding than a first-time founder with no track record or industry connections.

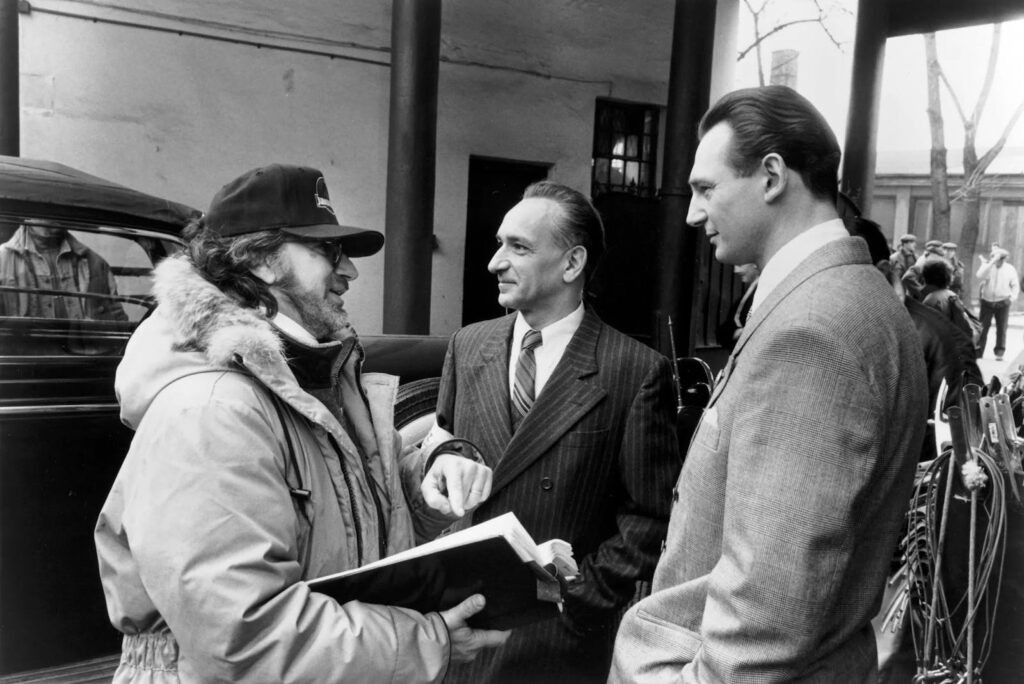

If Steven Spielberg wants ten million dollars for his next flick, his team could pull it together with a few phone calls and a luncheon. He could show up at any major film studio in the world, and walk out half an hour later, check in hand.

Film production studios are the world’s premier film financiers. These include some of the world’s biggest media conglomerates, including Universal, Warner Bros, and of course, Disney.

Disney really holds the crown here. They’ve produced 336 films, and are buying up the world’s major production companies left & right. Think Marvel, Pixar, Lucasfilm, and 20th Century (which is no longer called 20th Century Fox since Disney bought them in 2019).

They also produced the two highest-grossing films of all time: Avatar (both of them) and Avengers: Endgame.

How big budgets are split

Big movies don’t get funding from just one source. While studios can afford to fund & distribute entire films themselves, it’s pretty rare. Studios prefer to de-risk each project.

In a typical big-budget film:

- The studio itself may invest just 30%

- Foreign distributors often invest 10%

- Pre-sales are a huge and growing source of financing. This is a rights agreement between a studio and a distributor. (For example, a deal between Warner Bros and Netflix that lets Netflix air the film.)

- Private equity and hedge funds are becoming more prominent in the space. They invest in a slate of movies to mitigate risk.

- Product placement helps fill in the gaps.

Production companies vs studios

The difference between a production company and a production studio is that studios own all the rights to a project, whereas production companies only produce it.

And we can’t talk about production studios without talking about Netflix.

Netflix is the world’s most prolific studio. With 1,500 titles in their back pocket, the “kings of streaming” are making more films than any other company. (Some of these films are terrific, others are not )

This year Netflix has 16 Oscar nominations — nine of which are for All Quiet on the Western Front. This is the only streaming movie to snag a Best Picture nomination.

When Netflix buys the rights to a film, they pay for all the production costs upfront, but own the full rights forever. It’s a terrific model, but a double-edged sword.

Still, for filmmakers large and small, Netflix has become the first place you go for financing. They approve so many projects that it’s become a joke:

Indie film studios

If big-budget movies are about safe bets, independent films are about risk-taking.

To extend the VC metaphor, this world is about making small bets in low-budget flicks that could be huge.

What’s interesting about Netflix is that it’s both a big-budget studio and a medium-budget studio. They spend 17 billion per year on content, but most Netflix originals are in a range above low budget, but not “blockbuster” (from around $25m to $100m.)

But it’s not really a small-budget studio. For budgets under $20m, indie film studios and financiers are the first port-of-call.

Here are three you should know about:

A24 Films

A24 Films helped fund the incredible & terrifying 2018 film Hereditary (one of my favorite thrillers).

But their biggest win is Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Annapurna Pictures

Annapurna Pictures is responsible for films like American Hustle and chatbot love story, Her.

Owner Megan Ellison, is a billionaire, which is quite helpful, since most indie flicks don’t make any money.

30WEST

30WEST is an investment-focused studio that helps small and mid-sized films with their investment pitches and finding collaborators. In this way they’re almost like a movie accelerator,

They often do documentaries, and are the ones behind FYRE, Triangle of Sadness and I, Tonya.

Movie grants

Filmmakers can turn to grants if selling movie rights to an indie studio fails.

Most film grants are from the government. But grants are about more than just money; they also help budding filmmakers build connections.

Grants are usually genre-specific. For example, documentary grants are especially popular.

Filmmakers access grants through grant directories like:

Applying for grants is basically a full-time job. Prepare to get rejected like crazy, and even when you do land a grant, the average size is only around $5,000 – $10,000.

It’s not much, but it’s enough to make a film and launch a career. Just ask Robert Rodriguez.

Crowdfunding

Luckily, indie directors have another trick up their sleeves — crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding is turning into the backbone of independent film funding. Kickstarter is still the king, but there are specific film crowdfunding platforms.

Seed & Spark

Seed & Spark is the main niche player here.

The average film listed on the site is trying to raise $25k – and a whopping 80% of projects get fully funded! (To put that in perspective, Kickstarter’s success rate is just 40%)

Slated

Slated is another marketplace for film financing and dealmaking. They aim to connect a global network of investors, filmmakers, and industry professionals.

While Seed & Spark helps connect filmmakers with individuals who want to pitch in money to help launch the film, Slated focuses on accredited investors who can write bigger checks.

Crowdfunding success stories

Veronica Mars

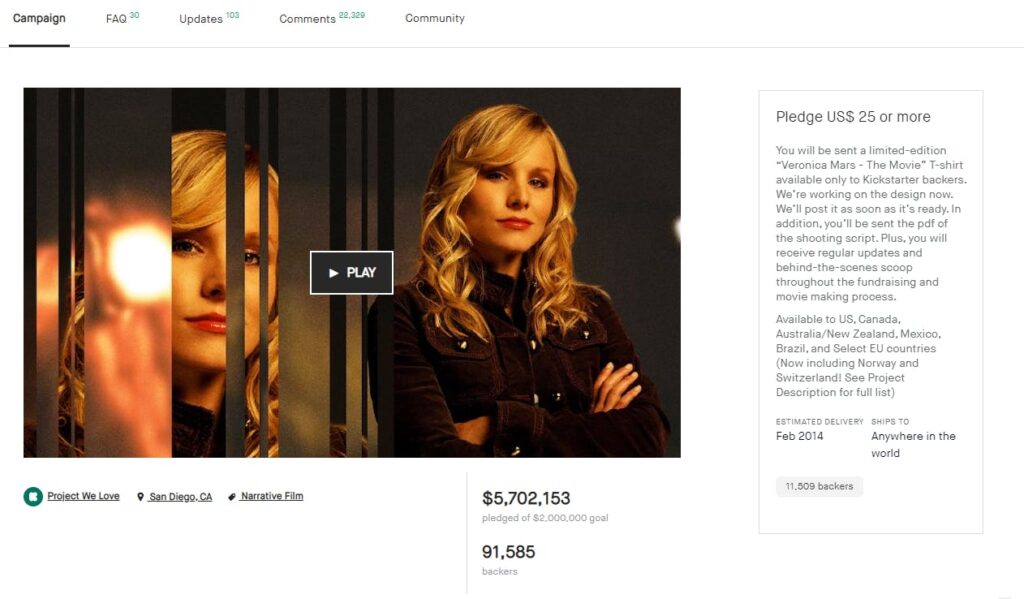

The biggest crowdfunding story to date is easily Veronica Mars.

Veronica Mars was a TV show that ran for 15 years (2004 – 2019) and was the first big break for Kristen Bell.

Despite a cult following, the show was canceled abruptly in 2007, leaving angry fans and an unresolved plot in its wake.

Dissatisfied, Kristen Bell and director Rob Thomas (not the guy from Matchbox Twenty) approached Warner Bros with a Veronica Mars film script. The studio declined, so the pair said screw it, and turned to Kickstarter.

In 2013, the crowdfunding campaign for a Veronica Mars film became the most successful Kickstarter ever (at the time) receiving nearly $2 million in funding in less than twelve hours.

All up, the project raked in $5.7m from 91,000 investors.

Fans are torn on whether or not the film was a box office success. It grossed $3.5m in theater sales, though given most of its budget was crowdfunded, nobody knows the exact profit margins.

However, the film was clearly a cultural hit, and still has an active subreddit.

The Chosen

The Chosen is a critically acclaimed period drama following the early life of Jesus Christ.

The crowdfunding campaign raised $11m in funding from 16,000 investors, and the team created its own indie film studio: Angel Studios.

What’s interesting about this deal was that investors weren’t just throwing their money at a “passion project” (pun intended). Everyone who committed at least $100 received an equity stake in The Chosen, LLC.

Shareholders are paid out from merchandise profits, show licensing deals and more. And if the company generates 120% profits, investors are paid out before the showrunners receive a dime.

Angel Studios (now called Angel.com) has retail investors, venture investors, and yes, angel investors on the cap table.

So it’s not really an “indie” studio anymore. To be honest, I don’t know how to classify it.

But it’s unique, and it’s working.

Night of the Living Dead

Night of the Living Dead is considered a cornerstone of the horror genre; a cult classic that revolutionized the modern zombie flick.

Critics hated it at the time because it was too violent. (You’ll see why that’s funny in a sec). But director George Romero’s cult classic was self-funded.

The story goes, a team of producers and directors pooled money for the film. Together, they raised $6,000, just enough to get it off the ground.

They eventually secured an additional $100k from production company Image Ten. (Image Ten is still around today, their entire brand revolves around Night of the Living Dead merch)

The film’s budget was relatively small, but this turned out to be a blessing. Night of the Living Dead didn’t rely on cheap effects to scare its audience.

Other success stories

- The Babadook. Aussie film producers raised $30m on Kickstarter to fund this terrific, unsettling supernatural horror flick.

- Wish I Was Here racked up $3.1m in crowdfunding, thanks to actor/director Zach Braff‘s influence.

- Blue Mountain State. Like Veronica Mars, this cult TV show was cancelled, raised $1.5m, and turned into a film.

What about Broadway?

Broadway financing is a whole other game. Ticket prices have outpaced inflation for decades, and broadway investing is still largely seen as an “older rich people game.”

It’s a tight-knit circle, and finding your way into the community can be tough. But it’s possible. Producer Lamar Richardson landed his first investments by cold-emailing congratulations to Tony Award winners.

Traditionally, broadway investors pay $100k+ to finance a show. But the process is becoming more accessible.

Take broadway financiers Steve Baruch and Ken Davenport. While their minimum investments are still in the six figures, these two have built email lists of serious broadway investors. Now, instead of one investor risking hundreds of thousands on just one show, a pool of investors creates a syndicate at $10k – $15k per investor.

If you’re interested, there are a few companies worth checking out:

- Sign up for Steve’s 54 Below mailing list to get investment opportunities

- Head over to The Broadway Investors Club by Jason Turchin. Scour their offerings and sign up.

- 42nd Club is a group of investors having a blast investing in and co-producing Broadway plays and musicals.

How many films are actually profitable?

Big-budget movie returns

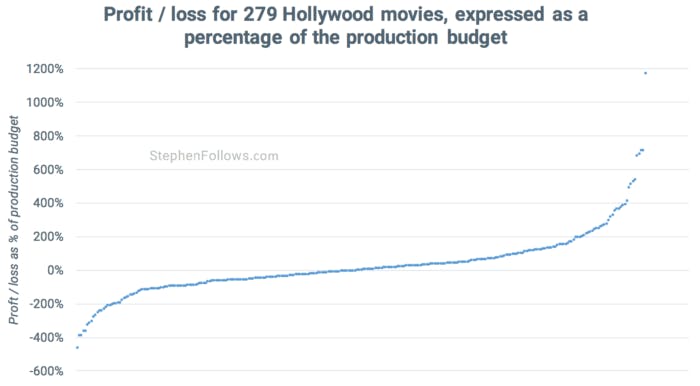

The average cost to produce a feature film sits between $100m – $150m. (Note: The average is skewed by outliers like Avatar, and median figures are tough to find.)

One common misconception (even Forbes runs with it) is that 80% of blockbusters fail to turn a profit. Most experts now agree this is simply untrue.

Data points toward a 50/50 split, with margins much tighter than you’d expect.

It’s a lopsided game. The overall win/loss split is roughly even, but losses can be tremendous.

Compare it to venture capital for a moment. While seed-stage investing is always risky, by the time a startup hits Series B and Series C rounds, escape velocity has usually been achieved, and the chances of losing money are greatly reduced.

But in filmmaking, all bets are off. You only get one chance to nail the revenue, and bad timing and poor marketing can sink a film into oblivion.

Indie movie returns

Independent films usually cost $2m at most, and most indie filmmakers try to make movies for around $25k. But while there’s less downside with indie films, the chances of success are much rarer.

Here’s a sobering stat: 97 percent of indie films fail to turn a profit. 😳

Oof.

It’s easy to see why investors are wary of financing this stuff.

Indie films don’t usually star Meryl Streep or Ryan Gosling (though nabbing a big star is probably the single best thing you can do to increase chances of success) and they have no easy distribution network. It’s rough out there.

This is why crowdfunding is the lifeblood of indie filmmakers. CF investors aren’t necessarily expecting to make money, they just want to provide support, get a few perks, solidify a connection to the filmmakers, etc.

Most of all, they just want to see the movie get made.

How much can film financiers earn?

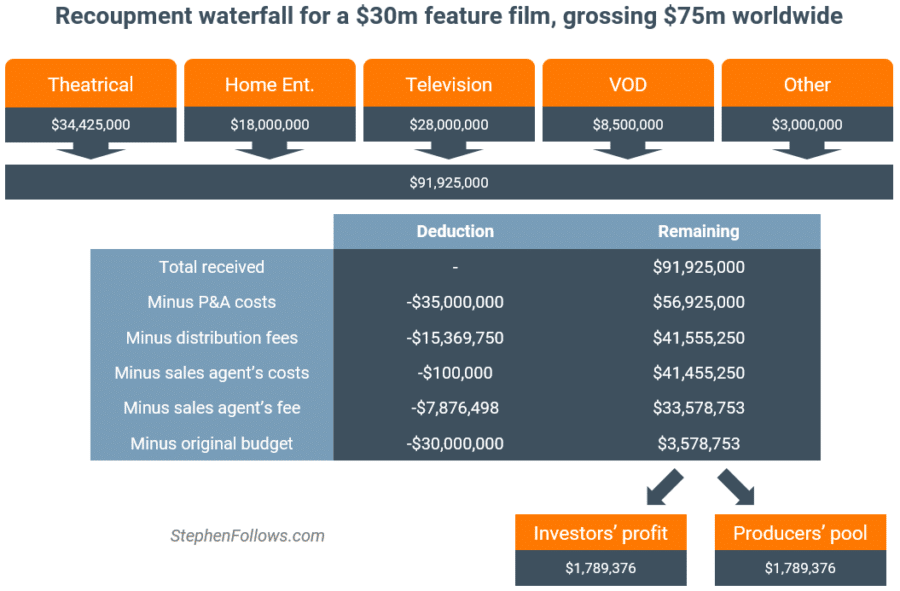

Film and TV profits are distributed in a chain known as the Recoupment waterfall.

There’s a pecking order of investors, producers and talent all waiting to get their slice of the pie, which turns into crumbs the further down you go.

Don’t forget that investors essentially need to pay for distribution, agents, marketing, everything. It adds up fast.

There are other factors to consider too:

- Theaters take a 40% – 50% cut off the top

- Distribution is between 27% – 30% of profits

- Sales agents get 20% of profits

- And if there’s any net profit left over, it’s taxed substantially. (Although some countries, including Australia, offer huge 40% tax breaks for feature films.)

Investors are one of the last people to see the net profits, often waiting 18+ months to get their share.

Though remember that the box office isn’t the end of the road. Other revenue streams like merchandising, home entertainment sales, spin-off series, video games, etc. can continue to pour in long after box office sales have finished up.

Closing thoughts

Film financing seems like one of the riskiest alternative investments out there.

The high-end Hollywood blockbusters are only accessible through hedge funds and private equity, and indie films have a shockingly low success rate.

When an indie movie lands, it seriously lands. But even then, the investor upside seems frustratingly limited.

Take The Blair Witch Project, for example. The 1999 horror film (btw why are so many indie films horror?) had a budget of $200k – $500k,

Rights to the film were picked up investor (and Mirimax CEO) Bill Block for about a million, and it went on to gross $249m. Great news, right?

Well, not really. If Block only saw 2% of profits (as the recoupment waterfall suggests), that would mean a $5m gain – or a 5x ROI.

Meh 🤷

One safer option is to provide capital as debt, rather than equity. This way, you can almost guarantee returns instead of relying on a film’s success.

Bottom line: Making a profit with indie films is basically unheard of.

But there’s more to investing than just money.

Financing a film grants you access to an exclusive club. It gives you the personal satisfaction of incubating a great project that, with your help, will see the light of day.

Investing in a film may not make you money. But there’s a good chance it’ll make you happy. 🎬

Further Reading

- A24: How This Small Indie Producer Dominated the Oscars

- Fourth Man Films makes the case that investing in an independent film company is one of the best investments you can make in your lifetime.

- The tropical Island of Nauru lost a fortune investing in a terrible musical based on Leonardo da Vinci (← crazy story)

- From the Heart Productions helps indie filmmakers get funding via grants. They’ve raised $30m since 1993.

- Peacock is a film and TV finance company with expertise in sourcing profitable projects and securing funds from independent investors.

- Sideshow Collectibles specializes in licensed and original life-like collectibles from movies and TV.

- Broadway World has a great article on How to Invest in a Broadway Show

Disclosures

- This issue was sponsored by our friends at Finlete and Investables

- We have no ALTS 1 or personal investments in any companies mentioned in this issue