Hello and welcome to our very first Art Insider for February 24th, 2022 – FREE edition.

We’ve been getting a lot of Art sign ups lately, and haven’t sent an issue on this subject before now.

So today’s content is a doubly special one – our very first Art Insider, plus a super in-depth look at the problems (and solutions) to art investing from our guest contributor, Jonathan T. D. Neil.

Let’s go!

Table of Contents

About Jonathan

Jonathan is one of the co-founders of Inversion Art, an investment accelerator program that acts as an artist services agency, providing support and guidance. He writes extensively for ArtReview, Hyperallergic, The Art Newspaper, and others, and is extremely knowledgeable of both the art and investment world.

In this article, he looks at Art as an alternative asset with a dynamic history and offers some brilliant ideas on how one of its crucial flaws can be transformed into a stable revenue-generating business.

Art as an Alt

The History

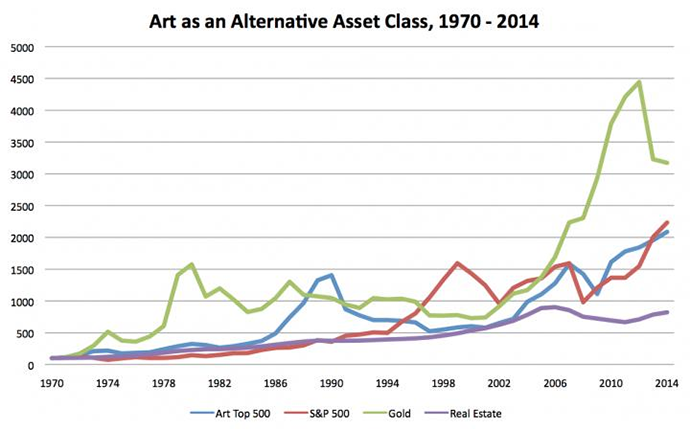

The conventional wisdom that fine art can serve as an “alternative investment” only became conventional recently.

In a matter of months after September 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, research papers emerged, confirming fine art could serve as a hedge when other investments headed south.

Deloitte published its first “Art and Finance Report” in 2011, covering the years following the global financial crisis when (expensive) art remained a relatively stable asset against the backdrop of cratering financial stocks and real estate markets.

Raya Mamarbachi, Marc Day, and Giampiero Favato of Henley Management College, UK published “Art as an Alternative Investment Asset,” further reconfirming one of the founding myths of how art can serve as an investment, which is that it isn’t correlated with equities markets, and as such, it is a nice diversifier in one’s broader investment portfolio.

The durability of “hard” assets

After the US stock market cratered on “Black Monday” in 1987, analysts began to notice that prices for other “hard” assets didn’t take the same hit.

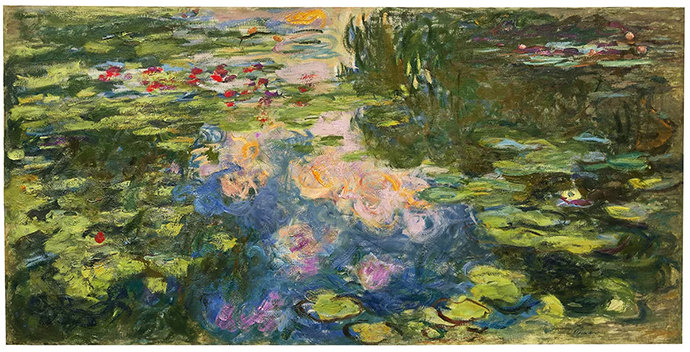

In fact, between 1987 and 1991, many once long-standing sales records for auctioned works of art, especially Impressionist paintings, made headlines. Van Gogh’s Irises (1889), sold for $53.9m in 1987, and Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890), sold for $82.5m three years later ($161m in today’s dollars), are only two of the most well-known examples.

The Problem

Which equities are we correlating to?

Buyers and sellers (and where they are) matter to markets, not just prices.

Between 1986 and 1991, Japanese equities and asset markets, particularly real estate, were running hot. But when the Japanese government intervened and popped the real-estate bubble, equities markets followed, and the flows of cash that had been propping up the headline-grabbing sales of paintings at auction (thus all of the other exuberant purchases downstream) quickly dried up.

By the end of 1992, the art market globally resembled a post-gold-rush ghost town.

The 2008 financial crisis was a different story – while the art market in 2009 felt pretty dreary, most of the wealthy who had been collecting art over the previous decade didn’t feel immediately strapped for cash.

By 2011, more savvy analysts like William N. Goetzmann had firmly demonstrated that fine art prices and equities (as well as incomes!) were very well correlated indeed.

If art is an investment, it certainly isn’t an alternative one in the sense that portfolio theory would understand it.

What about the revenue?

The other problem with the conventional wisdom on art’s capacities as an alternative investment has less to do with how it came to be (wrongly) conventional and more to do with art itself – that it doesn’t generate revenue.

Its value is tied only to how much the next person wants it, not to what it can produce or do.

Sure, works of art have aesthetic value and other sorts of satisfactions, other sorts of utility. But that utility is very rarely put to work in the creation of other utilities, which can translate into revenue streams. (I say “very rarely” because recently the advent of commercial fine art leasing programs have begun to show some promise, on which more below.)

The greatest collector of all time, Warren Buffett, who famously doesn’t collect art, just dollars, put this nicely in a different context. Art is one of those assets that won’t produce anything but is purchased in the buyer’s hope that someone else will pay more for it in the future.

Over the long term, a bet on the next person’s desire is not a good bet; bets on the next person’s needs, on solutions to their problems/challenges, on opportunities increasing their purchasing power – those are good bets, and that is where one should look for alternatives to art as an investment.

So, should we give up on Art?

Rather than giving up on art as an alt overall, it’s about switching the focus to the challenges (and opportunities) facing the arts in general.

Let’s take a look at some of the options open to investors.

The Solution

What follows are just a few possibilities that will expand the fields of art production, consumption, and infrastructure in the future, if, that is, they find the right alternative investors:

Gallery equity partnerships

The one thing that plagues most contemporary art galleries from the middle-tier down is a lack of capital or access to it.

The consignment model followed by most commercial galleries dealing in contemporary art has artists financing gallery operations with their own inventory.

This arrangement aligns with both parties’ interests, but it disadvantages the artists who shoulder most of the risk.

Greater capitalization would allow galleries to actually invest in their artists by buying inventory and then selling dear when the time comes, either in the short term as an artist’s work achieves market traction or in the long term, as institutional recognition adds value to an artist’s reputation.

Think of it as “every gallery – an art fund,” but funds that take an active (activist?) hand in managing their investments and producing new value.

Transaction facilitation

One issue that plagues the international art market is a lack of liquidity compounded by transaction (invoice) aging.

Quite often, the larger the transaction, the slower it is to clear. Historically, fine art auctions have provided the most expedient clearing mechanism in the industry, but auction transactions only account for, on some estimates, 40% of the global trade in art and collectibles.

However, some new ventures have recently popped up to tackle this problem.

The Australia-based ArtMoney, for example, provides collectors the opportunity to divide their purchases into 10 payments, with interest on the financing of the upfront purchase paid by the gallery.

Because it’s designed like a credit instrument, purchase prices are capped (to mitigate risk), but in principle, there is nothing holding ventures like these back from providing the clearing mechanism that the art (and collectibles) market truly needs. Escrow and invoice factoring models are equally compelling opportunities in this space.

And there will be knock-on effects: whoever captures a large enough share of this market will have proprietary information on non-auction transactions, something notoriously difficult to come by and thus – highly valuable in its own right.

Art Leasing

The challenges to art leasing are more cultural than operational. Collectors want to own their work, not lease it. Loans are risky, and insurance is expensive. And the quality of the work on offer has often been subpar and considered “merely” decorative, the kinds of stuff that adorns down-market corporate lobbies and corridors.

Creative Art Partners overcomes those challenges by drawing on a vast collection of established and emerging contemporary artists, many recently out of MFA programs and discovered via Instagram and other social media platforms. C.A.P. provides its clients – high-end real estate firms and other boutique but high-style corporate entities (like the talent agency ICM Partners), and (increasingly) individuals too, with “real” art, as well as the logistics and handling services to move, curate and hang it.

Given the increasing numbers of people and firms that don’t want to carry these assets on a balance sheet but need visual art to set the culture and tone of their businesses or personal brands, the art leasing business is poised for growth in the decade to come.

Skills Platforms

We are all familiar with these platforms in other sectors. In the U.S., DoorDash does food deliveries, and TaskRabbit will get you someone to put your furniture together or paint a wall. These gig-economy jobs are designed for the low-skilled and opportunistic part-timer, but I think we will see much more differentiation soon, with new platforms catering to specific sectors and specific kinds of work.

The challenge will be building a big-enough network of customers and providers, but the arts sector is a prime market for just this kind of two-sided gig-based enterprise.

As the ranks of collectors and museums grow, there will be increasing demand for well-trained and well-vetted art handlers, shippers, appraisers, and temp workers who understand the context and the material they are working with. An app that aggregates this skilled labor and connects it with the broadest pool of clients will create immense value for both sides.

Trade Schools

The real payoff will come when these platforms enter the technical training space, providing credentials when particularly difficult-to-achieve skillsets are learned and practiced (like custom crating for paintings with delicate surfaces or finishes that need to ship internationally).

Right now, these services are dominated by the big art logistics companies, but it’s not the companies that have the skills – the workers do, and they are only learned if someone new joins the company and is taught them. This apprenticeship model keeps others from entering the same business.

A trade “school” platform has the potential to aggregate that knowledge base and democratize it.

Conclusion

The rise of art financing

Too often, just the vernacular of “investment” drives funders to think only of the financial sector.

That is certainly one area where we have seen substantial growth in new enterprises offering to “unlock” the value of art for the high-net-worth collector.

In 2011, the opening pages of Deloitte’s First Art & Finance report were dominated by advertisements for fine art insurance; in 2019, the majority of the opening ad space was bought by firms, many of them new, offering art financing.

And like “finance,” one of the reasons that “investment” has often received a bad rap in the art world is that it is exclusively focused on the product, to the producer’s detriment.

Meet the artist accelerators

Artists who have begun to gain market traction and are beginning to get attention from institutions often don’t have the knowledge or means to scale their operations. If they are very lucky, they have a gallery or a mentor to help them.

But in most cases, they do not, and this lack of support (in time, capital, knowledge, and networks) means the difference between being subject to the whims of the marketplace and its institutions and having full leverage over one’s own career.

Having witnessed how this misalignment of incentives can undermine artists’ careers, my business partner and I started a company that seeks to reverse this prioritization of product over producer, work over talent, through an investment model that delivers to artists the capital, strategic planning, and access to new networks that will help accelerate their careers and set them up for long-term sustainable success.

The art world is often slow to adopt (adapt to) new models that have found success in parallel sectors. It may seem counterintuitive, but there are striking parallels between the primary markets for contemporary art and the venture capital market for startups.

My co-founder and I were inspired by Y Combinator, another company that has prioritized founders, not just the services or products that their companies promise to deliver, with great success.

The accelerator model is one that startup culture is very familiar with, but it’s new for the art world, and for artists, who are more accustomed to “residency” programs with no long-term stake in their success, and career “workshops,” which try to teach artists to be their own accountants and marketers and legal counsel. This is not what we need artists to be.

A vision of freedom, means and network

InversionArt and its LPs have a stake in the long-term success of their artists, both through the work that Inversion collects and through the services that Inversion provides.

Like the examples above, this is an important alternative to existing models of doing business in the art world, one that puts artists’ interests first by creating a company that aligns the interests of artists and their “investors” over the long term. I believe that’s an alternative worth investing in.

But the greater lesson here is that when it comes to investing in alternative assets, the emerging ventures to service those assets (or, more importantly, that are promising to change how those assets are managed, transacted, and valued) should also be considered.