Today, we’re going to explore the relatively new and quickly-growing esports industry.

In the next few weeks, two of the biggest esports events in the world will have concluded. The League of Legends World Championship, and the Dota 2 International Tournament (aka T.I.) which will create ten young millionaires overnight.

Competitive gaming has come a long way in the past twenty years. It’s evolved from basement LAN parties to a heavily sponsored, professional spectacle worth billions.

But how did esports get so big, and where are the investment opportunities today?

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

What are esports?

Esports are multiplayer video games played in organized competitions.

They comprise anything from small events at local Internet cafes to multinational tournaments played in dedicated arenas in front of thousands of spectators (Gaming arenas are rather small, though the very largest tournaments can sell out NBA-sized arenas.)

The players are considered professional gamers, though for many of them it’s a part-time job that simply pays the bills. Others make a full-time living from prize winnings and endorsements — stuff like hardware, graphics cards, and energy drinks.

But the craziest concept is the esports version of real-life sports.

That’s right — some of the industry’s most popular competitive games are FIFA, NBA2K, and Madden. Instead of watching real athletes, people watch other people play as those athletes. And for a sh*tload of money.

Many of the biggest social media influencers started by streaming themselves playing video games. One of the world’s most famous p*rn stars, Sasha Grey, regularly streams games on Twitch. (In researching this piece, we realized there’s actually a large revolving door between esports and p*rn. Definitely NSFW, but Google it if you’d like.)

The history of esports

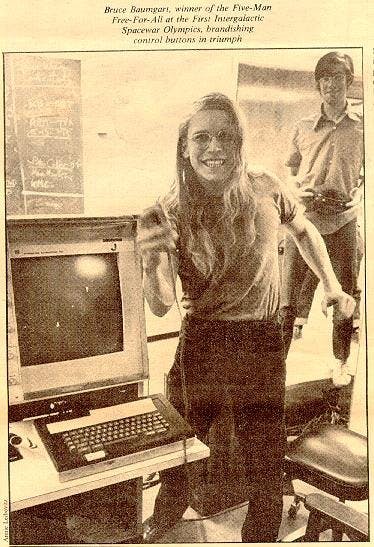

The history of esports traces back to October 1972, with the first video game competition in a Stanford University computer lab. 25 players faced off against each other in a game of Spacewar!.

You used a joystick to control a spacecraft, launching torpedoes at your enemy while working around obstacles and fighting gravitational pulls.

The tournament was promoted on the Stanford campus, and got huge press. Rolling Stone was there. It was photographed by the famous Annie Liebovitz.

After the Stanford tournament in 1972, esports continued to evolve. With the creation of the US National Video Game Team in 1983, more organized competitions followed.

Video game tournaments soon became big enough for the big screen.

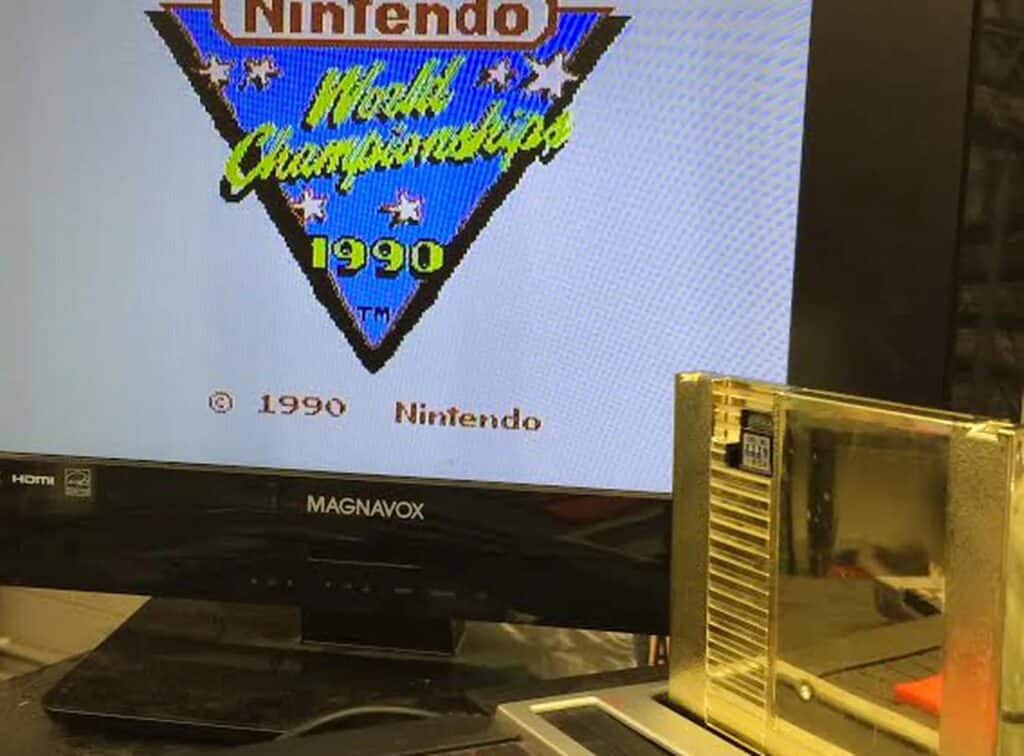

Anyone remember the 1989 movie, The Wizard? It ends with a nail-biting scene at a Nintendo competition. The movie proved prescient — or at least a very good marketing tool.

In 1990, the first Nintendo World Championship event was held in the United States, touring 29 cities to crown City Champions.

The evolution of esports

Today, esports are bigger than ever:

- The global esports market is $1.2 billion.

- The Top 10 esports teams are all worth over $200m. Valuations are up 50%+ since 2020.

- In 2021, the Dota 2 International tournament in Bucharest had a record total prize pool of $40m.

- The winners, Team Spirit from Russia (now headquartered in Serbia) took home $18m — split among 7 team members. This was the highest amount ever won by an esports team.

- Tourney viewership hit 2.7 million (excluding those from China which we don’t know about)

- The International Esports Federation (IEF), the global governing body, counts 128 member nations, including Taiwan and Kosovo (which aren’t even recognized by the UN)

To reach this stage, esports had to go through some major changes.

Gameline

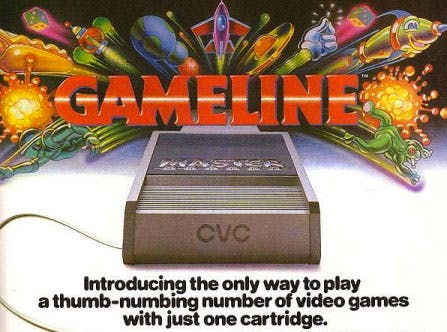

Back in 1972, long before wireless Internet, gamers could only play against each other in person, in what’s known as a LAN party. It stayed that way for 30 years, until the Internet eliminated all boundaries and introduced 24/7 global competition.

Downloadable video game software was around as early as 1983, with the creation of Atari’s CVC Gameline.

Runescape

When Runescape was released in 2001, a new era of gaming really began.

Categorized as an MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game), it allowed players worldwide to play, interact and chat with each other.

The ability to communicate with other players over the Internet changed how people viewed video games, and led to the whopping 3.2 billion global gamers we have today.

Twitch

You cannot talk about esports without mentioning the streaming platform Twitch.

Founded by Justin Kan and bought by Amazon in 2014, Twitch is a massive reason for esports’ popularity and success. There are other game streaming platforms — ESL, Mixer (owned by Microsoft), and Azubu. But Twitch’s reach far surpasses any other platform.

NACE

In 2016, the National Association of Collegiate Esports (NACE) was founded.

NACE is a nonprofit organization that develops and promotes esports programs at the collegiate level. They lobby for colleges and universities to offer gaming scholarships, and got a victory in 2019, when Harrisburg University became the first university to offer full scholarships for competitive gaming.

The life of a pro gamer

With the rise in popularity, the stakes have gotten higher. Top streamers can earn up to $20,000 per hour, and leagues offer lucrative contracts for the best players.

Being a pro gamer may sound easy, but they hustle. Spending 10 to 12 hours per day playing a single game is normal. So is paying for physical therapists and psychologists. This is no surprise in a world where self-identity is so closely tied to performance.

Players sit for hours on end, and all the ergonomics in the world can’t save them from back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and hand fatigue. The average pro gamer retires before 25 — meaning their career lasts 2.5 years shorter than NFL players!

One of the most dangerous effects of being a pro gamer is that self-identity becomes tied to performance. Especially in younger players, this can be especially difficult to manage.

Who are the top players in esports?

Despite the short window of time gamers get to prove themselves, plenty have left their mark on the world.

Jonathan Wendel 🇺🇸

American Wendel (aka Fatal1ty) is considered the original pro gamer.

Active from 1999-2008, he was an esports pioneer, making a name for himself in first-person shooter games like Quake and Painkiller.

Wendel competed back when most tournament rewards maxed out at a few thousand bucks, so his $450k in lifetime earnings aren’t very high by today’s standards.

But not to worry: Just like in “real” sports, players can earn even more from their brand than from actually playing the game. After retirement, Wendel started his esports lifestyle brand, Fatl1ty, Inc. He sells mousepads, gaming chairs and desks, snacks, and motherboards, and is worth an estimated $4m.

Johan Sundstein 🇩🇰

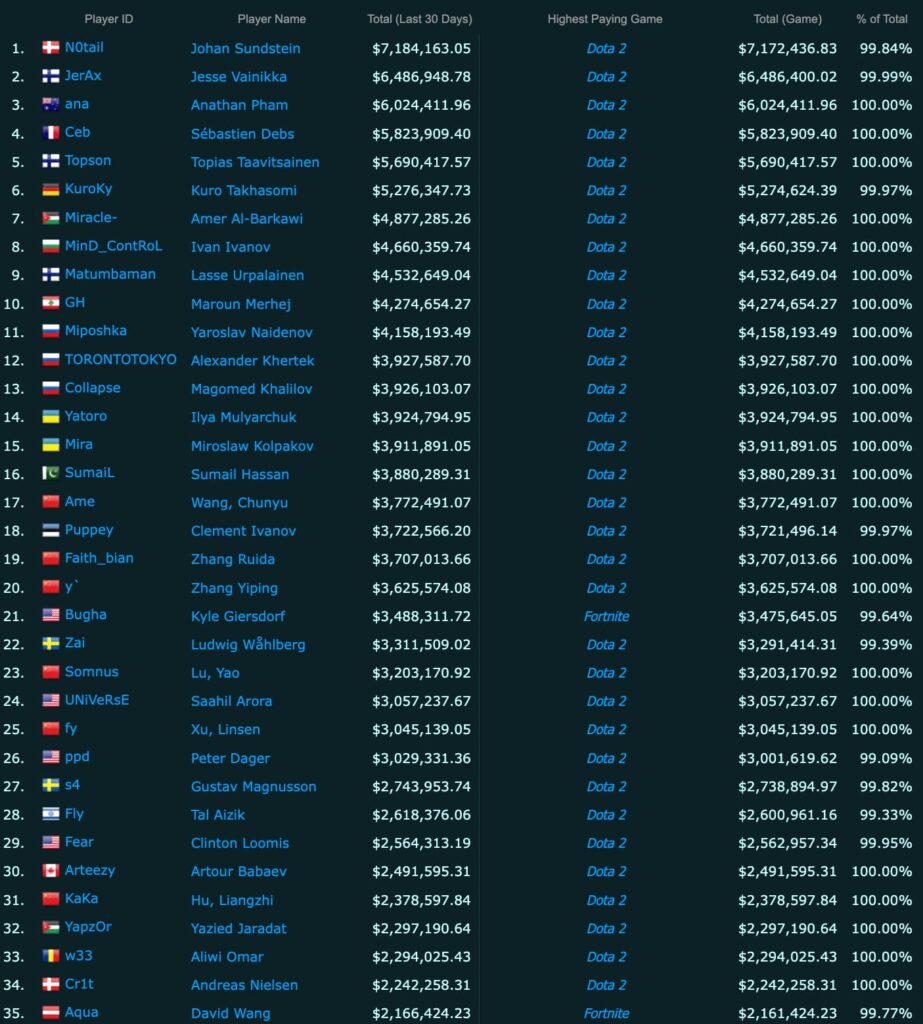

Danish-born Sundstein (aka n0tail) is the all-time leader in esports earnings, with more than $7.1m in career winnings.

Sundstein became a professional player at age 15, specializing in the game Heroes of Newerth. When Heroes started to lose popularity, Sundstein switched over to Dota 2.

Last year, after 13 years of competitive gaming, Sundstein announced he was taking a break.

Danil Ishutin 🇺🇦

Ukrainian Danil Ishutin (better known as Dendi) won the very first Dota International Tournament in 2011, and is hugely responsible for making Dota grow so fast in its early years.

Dendi began playing professionally as a 16-year-old, breaking through in 2010 with a third-place in a highly competitive World Dota Championship.

Mainstream investing in esports

Activision

Activision Blizzard ($ATVI) is a game developer who owns some of the most valuable esports leagues in the world. The stock has held up well during the 2022 equities crash.

Draftkings

Draftkings ($DKNG) is another stock to consider. While known as a sports betting company, Draftkings has quickly become the leading platform for esports betting. Last year, they announced a partnership with FaZe Clan (more on them below) to create daily fantasy competitions, sponsor new content, and provide a greater presence at tournaments.

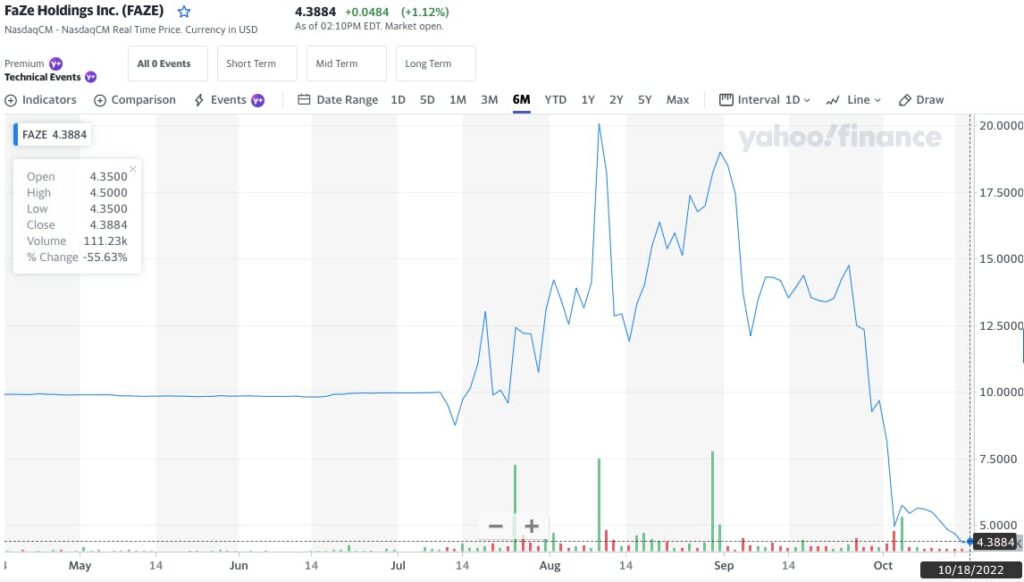

FaZe Holdings

FaZe Clan ($FAZE) is an esports lifestyle brand. This past July, they became the first esports and gamer company listed on the NASDAQ. Forbes recently gave Faze a valuation of $400M.

EA

Electronic Arts ($EA) is a game developer whose stock has also been pretty steady. They recently announced a competitive gaming division.

More stocks and ETFs

Professional esports teams count on graphics cards from NVIDIA. And there’s always Tencent, who owns Riot Games, who owns League of Legends.

Alternative investing in esports

But equities aren’t the only play here. There are some good alternative investment opportunities as well.

Buying esports teams

Just like owning physical sports teams, buying full or partial ownership of esports teams is entirely possible.

But for teams who are serious about competing professionally, expenses add up. Keep an eye out for new and upcoming local teams/leagues. Get in contact and see if they’d be interested in taking investors. Inquire about sponsorship opportunities or even equity opportunities.

Consider the geographic location if you’re looking to buy a team outright. China, Korea, and Europe are all high-performance regions with a disproportionate number of winners. Australia’s esports ecosystem isn’t well-developed, so investing there is too early at best, and a terrible idea at worst. North American esports isn’t great for players, but can be very good for investors.

Esports franchising

Esports franchises are a relatively new phenomenon that are becoming increasingly common.

It basically works like this:

- A central coordinator creates a franchised league.

- Teams pay the coordinator for a permanent spot in the league. This is a big difference between non-franchised leagues, where underperforming teams routinely get relegated. But this stability comes at a cost. Expect to pay about a million dollars for a spot.

- Investors & owners run their franchise team like any other franchise business. Players get a salary, work benefits, and a cut of the winnings. (This world is surprisingly well-structured, with player unions and minimum salaries)

- Teams own their permanent spot in the league until they sell the rights to another team.

Franchising heavily relies on marketing and sponsorship, though teams get additional support from league coordinators. Since all teams share venues, ticket & merchandise sales are split among teams. The real returns come from tournament prize money and team-level endorsements.

In the future, team owners are mulling the idea of creating their own arenas to achieve true “home-field” advantage.

Valhallan

It’s interesting to see the franchising sub-economy develop.

Valhallan franchises its services to help aspiring esports managers create their own teams. They lend their expertise in training, curriculum, and tournament play. Franchisees can build a studio for ~$75k, or an arena to train professional gamers for ~$150k

In June 2022, Valhallan acquired the North American ESports League (NAEL), the largest esports youth league in North America, with more than 100 teams.

XP League

XP League is another promising startup. They provide a launch plan to help franchise leagues get off the ground.

Esports criticism and closing thoughts

Esports has been a big business for a while now, and is intent on getting bigger. But like many investments these days, the market looks choppy.

There is hesitancy among the ranks. Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, who built a 12,000 square-foot training center for Mavs Gaming (the NBA2K affiliate of the Mavericks), has criticized the esports industry.

Cuban called esports an “awful business,” citing relatively low viewership for non-marquee tournaments, and the costs of training a successful team. He did note that Asian and European markets have healthier business demographics than North America. But still, his words hit hard.

In addition, this year’s T.I. has been criticized for its poor streaming quality, and the prize pool is the lowest it has been in seven years.

There are challenges to overcome before esports goes mainstream. But I think it’s important to remember how global esports is.

This isn’t just fun and games; esports will be a $5b industry by 2030. There will always be ups & downs, but gaming’s worldwide appeal isn’t going away.