Today we’re exploring the concept of voice ownership.

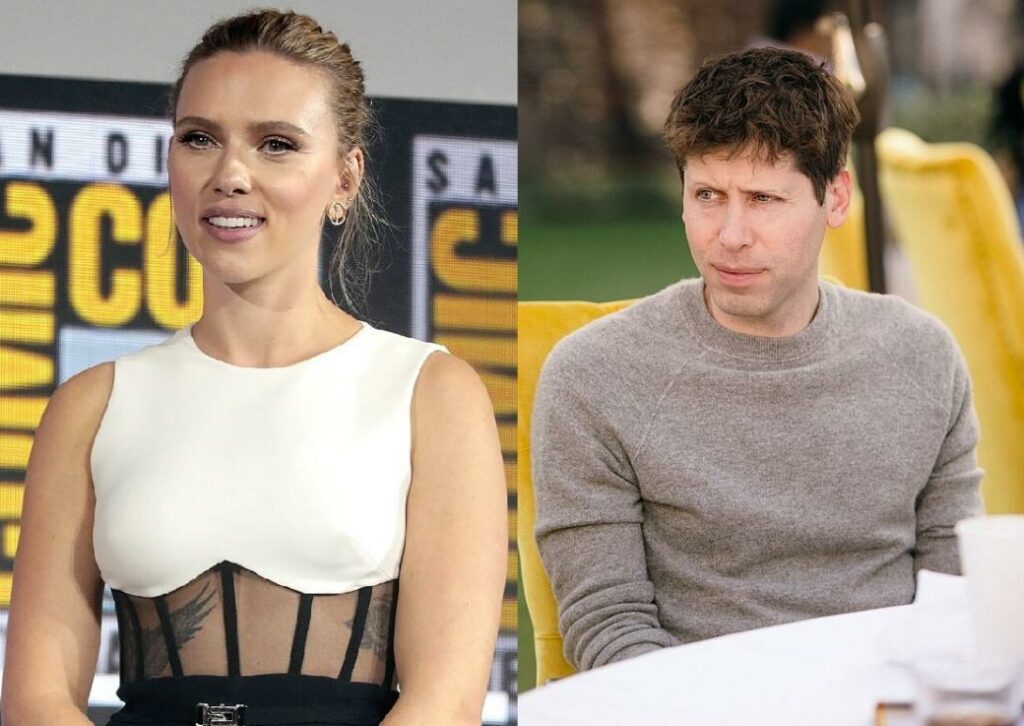

It’s no secret that OpenAI has had a rough couple of weeks.

Chief Scientist Ilya Sutskever abruptly left the company, and new details emerged about the harsh contracts OpenAI uses to limit employee dissent.

However, the biggest scandal this week was OpenAI’s release of their voice for ChatGPT, which they call Sky.

Immediately after hearing it, people recognized the voice as sounding eerily similar to actress Scarlett Johannson — including Johannson herself).

In response to the blowback, OpenAI yanked the Sky voice from ChatGPT “out of respect for Ms. Johannson,” in the words of CEO Sam Altman.

At this point, it’s clear that OpenAI really wanted to work with Scarlett, who said no. But it’s unclear that OpenAI used Scarlett’s voice as training data to create the Sky model.

Since the story broke, the internet has been lost in an ocean of confusion. Misinformation is everywhere, with tons of conflicting reports about whether OpenAI actually broke any laws.

Today, we’re going to break this all down for you in simple terms.

I’ll show how OpenAI could still get in legal trouble even if they never used Scarlett’s actual voice.

We’ll also explain why “owning” your voice is a lot harder than you think, and what this episode tells us about the future of AI regulation.

Note: This piece contains a lot of legal speculation. Since this incident is unfolding in the US, we’ll only discuss US regulations. As always, we’re not lawyers, and this is most definitely not legal advice.

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

Do you own your own voice?

Before the Sky scandal, OpenAI’s most high-profile battle was with The New York Times (and other newspapers) over using copyrighted material for ChatGPT training data.

Let’s be crystal clear: These are two separate issues here, and the legal problems with Sky are not about copyright.

Surprising as it may seem, you cannot copyright your own voice! So by definition, an AI tool replicating your voice cannot be a copyright issue.

Why are you unable to copyright your own voice?

As you may remember from our piece on intellectual property, copyright is all about protecting the expression of an idea.

Your voice is not an idea. Instead, it’s a tool. It allows you to express ideas, which can definitely be copyrighted if you record them.

Trying to copyright your voice would be like trying to copyright your legs because they helped you win a marathon, or your fingers because they help you become an artist. It wouldn’t make sense.

(And, no, you can’t trademark your voice either — but you can trademark specific expressions.)

Although your voice cannot be protected by copyright, it can be protected with a different kind of intellectual property right — the right of publicity.

Publicity rights protect ‘voice misappropriation’ (sometimes)

The basic theory behind publicity rights is intuitive.

You, and only you, should be able to determine who can profit from using your identity (like your name, face, voice, etc..)

Sounds simple! But in practice, publicity rights are deceptively complicated.

One reason why is that, unlike other forms of intellectual property rights, the United States has no federal law establishing the right to publicity.

Instead, the law here is a bizarre mishmash of state regulations; some of which are statutory (rules established by state congresses) and others which are common law (rules established by judges when deciding cases).

Thankfully, for our purposes, the three most relevant legal precedents for the ScarJo/Sky episode all occurred in California — the same state where a lawsuit between Scarlett Johansson and OpenAI would most likely take place.

The core idea linking these cases is whether a company “passed off” a celebrity’s identity — i.e., willfully misrepresented that a celebrity did something they didn’t.

Let’s look at the precedents here.

Case 1: Sinatra v Goodyear (1970)

In this case, Goodyear wanted to use a variation of the popular Nancy Sinatra song These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ to promote their new “wide boots” tires.

- Goodyear asked Sinatra to work with them

- She refused

- After securing a copyright license, Goodyear modified the original song for use in a series of commercials.

- Sinatra sued, arguing that the song was so strongly identified with her that viewers would think she participated in the commercials.

The commercial is pure 70s:

But Sinatra ended up losing.

In the commercials, the songs were performed by either a lone woman, or a group of women.

In the court’s eyes, these performances were distinct enough that Goodyear “did not pass-off; that is, they did not mislead the public into thinking their commercials were the product of [Sinatra].”

Case 2: Midler v Ford (1988)

Eighteen years after Sinatra v Goodyear, this case laid the groundwork for modern voice misappropriation law.

It involved a dispute between Bette Midler and another auto industry giant: Ford.

Here’s what happened:

- Ford asked Midler to perform one of her songs for a commercial

- Midler refused.

- Ford hired one of Midler’s backup singers instead, and told them to mimic Midler’s voice.

- As a result, Midler’s voice was still identifiable in the commercial. So she sued.

The doomed Ford commercial that sparked the original voice misappropriation case:

In this case, Bette Midler ended up winning.

The court found that since Ford deliberately imitated Midler’s distinctive voice in order to sell a product, they’d unfairly appropriated it.

Specifically, the court noted, “When a voice is a sufficient amount of a celebrity’s identity, the right of publicity protects it.”

Case 3: Waits v Frito-Lay (1992)

Finally, the case that cemented the Midler ruling was a dispute between musician Tom Waits and Frito-Lay:

- Frito-Lay wanted a commercial featuring Waits’ distinct, raspy voice

- Waits was outspoken about musicians not doing commercials, so Frito-Lay didn’t even bother asking him for permission

- Frito-Lay hired a soundalike recommended by their ad agency as “someone who did a good Tom Waits imitation”

- Waits sued

Along the same grounds as Midler, Waits won.

Frito-Lay was forced to pay damages for misappropriating Waits’ voice for commercial gain.

These cases help illustrate three important factors when it comes to the idea of voice misappropriation:

- The distinctiveness of the performance

- The motivation of the company, and

- Whether the voice is a “sufficient part” of someone’s identity

How strong is Johansson’s legal case?

First, we need to clarify something the internet seems to be getting wrong (shocking):

There is no indication Scarlett Johansson has actually filed a lawsuit against OpenAI.

Instead, she just had her lawyers contact the company, which was enough for OpenAI to pull the Sky voice and release a detailed blog post on how the voices for ChatGPT were chosen.

But why did OpenAI pull Sky so quickly? Is the law really on ScarJo’s side? Or is OpenAI just managing optics?

Sky is clearly inspired by ScarJo

I don’t think there’s any doubt that OpenAI (especially CEO Sam Altman) wanted Sky to evoke Scarlett Johansson’s voice — particulary, Scarlett’s performance as the AI “Samantha” from the 2013 film, Her.

- OpenAI tried to get Scarlett to work with them multiple times.

- Sam tweeted a single word, “her” on the same day as the upgraded Sky release. (omg, why?)

- And Sky’s vocal intonations, from the raspiness to the low-level flirtation, are obviously reminiscent of Samantha.

But there’s a world of difference between evoking and imitating.

In their blog post, OpenAI claims that Sky is voiced by a professional voice actor based on live studio recordings.

Meanwhile, reporting from the Washington Post indicates that the voice actor was hired before OpenAI reached out to Scarlett, and that the casting call did not mention Scarlett’s name. (This is critical.)

Personally, I do not think OpenAI actually used clips of Samantha/Scarlett as training data to create the Sky voice.

While Sam & Co. clearly don’t have a problem playing fast and loose with copyrighted material, I also suspect they’re smart enough to know that using Scarlett’s voice as training data would make an argument that they’re not imitating her a lot shakier.

That’s especially true since Scarlett’s voice is almost certainly protected by publicity rights.

While previous publicity rights cases mostly involved singers, Scarlett’s speaking voice alone is distinct and recognizable.

But remember, as the precedent cases show, using a soundalike is not enough for OpenAI to avoid legal hot water.

What really matters here is whether they attempted to “pass off” Sky as being Scarlett.

Did OpenAI mislead the public?

I have a confession to make: I don’t think Sky and Scarlett sound all that similar.

I might be in the minority here, but after reading about the uproar and listening to Sky, I was surprised at how…different the voices seemed.

Sure, the two voices sound related. They both have that classic California quirk known as “vocal fry.”

But in a blind test, I’m confident that I’d be able to identify which is which every single time.

While similarity is in the ear of the beholder, my (biased) opinion is that it would be hard to argue that OpenAI tried to mislead the public into thinking Sky is voiced by Scarlett, when the two sound so different.

Actual lawyers, though, seem to disagree with me! (And Sam’s “her” tweet certainly doesn’t help OpenAI’s case.)

But if it’s true that the company didn’t reach out to Scarlett until after hiring Sky’s voice actor (and didn’t mention Scarlett’s name in the casting call or in their acting directions), then OpenAI’s position looks much, much stronger than Frito Lay’s or Ford’s.

ScarJo might not need to win in a court of law, since she’s already won in the court of public opinion.

But this episode does showcase the novel problems AI creates for identity misappropriation — and the fact that our legal system is wholly unprepared for an AI-driven future.

The law needs to catch up to AI

It’s not hard to see why the Sky incident sparked such a strong backlash against OpenAI.

On the one hand, people do really like using AI. Adoption is through the roof. ChatGPT is the single fastest-growing consumer tech tool in history.

On the other hand, this incident perfectly encapsulates some of the fears people have surrounding AI — like, oh I don’t know, their very identity being hijacked by tools that can flawlessly replicate their faces and voices without their consent (aka deepfakes).

And here’s the scary part: when it comes to identity misappropriation, regular people have far less protection than celebrities.

Why? Because celebrities and public figures are basically the only people with publicity rights!

Determining whether someone can enforce publicity rights is partly about determining whether misappropriation of their identity is “likely to cause damage to the commercial value of that persona.”

Since the name, face, and voice of a “regular person” have basically no commercial value, it’s hard to argue that a non-celebrity has any publicity rights at all.

11 years after the Midler case was decided, a woman named Geneva Burger brought a case against Priority Records for using a recording of her voice in a rap song called No Limit.

Burger’s voice can be heard in the first four seconds of the song. It was surreptitiously recorded by her grandson’s friend during a phone conversation.

Burger was upset about the use of her voice in the song, and, just like Bette Midler and Tom Waits, pursued a voice misappropriation claim.

(Although, curiously, she never brought a case against the man who illegally recorded the conversation.)

Priority ended up settling before the case went to trial. But the studio would probably have ended up winning anyways.

In fact, one justice on the court panel noted:

As Burger concedes, her voice is neither widely known nor distinctive. It is undisputed that she is not a celebrity. For these reasons, she has no cause of action against Priority Records. (emphasis mine)

Now remember, we’re talking about cutting-edge technology here. It’s hard to apply decades-old court cases to modern AI.

But since so much of misappropriation law is tied up with publicity rights and the commercial value of an identity, it’s unclear what kind of legal protections a regular person would have if their face or voice were co-opted as the personality for some new AI chatbot.

By now, most people are familiar with Her. But perhaps they should also become familiar with Black Mirror.

The concept of AI owning your identity was the premise of Black Mirror’s S6E1 Joan is Awful, which depicted a woman who has her day-to-day life (and identity) used as material for a computer-generated TV show.

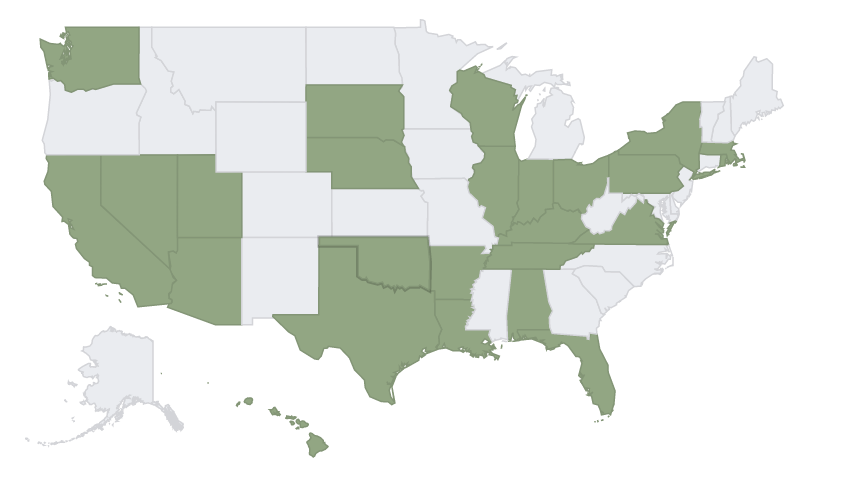

Today, states are building an eclectic patchwork of laws to try and regulate all this.

States with new laws surrounding the use of deepfakes (usually in an electoral or “revenge porn” context) include California, Michigan, Virginia, and Texas.

But there’s still no comprehensive national framework for dealing with identity rights.

I won’t pretend to know exactly what that framework should consist of or how to balance restrictions with free speech considerations.

But you shouldn’t need to be a celebrity to be entitled to determine how your identity is used. With any luck, the Sky/Scarlett episode will motivate new legislative action.

That’s all for today.

Reply with comments. We read everything.

See you next time, Brian

Disclosures

- This issue was sponsored by Jurny

- The ALTS 1 Fund has no holdings in any companies mentioned in this issue

- This issue contains no affiliate links