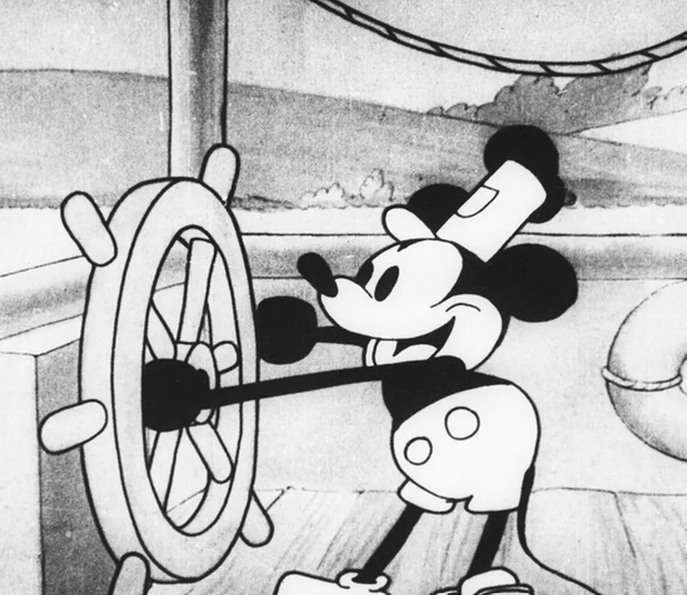

Last week, the very first version of Mickey Mouse fell into the public domain, joining formerly trademarked legends like Peter Pan, Winnie the Pooh, and Bambi.

But what does this actually mean?

Intellectual property a complex world, and it’s constantly under attack.

Today, Brian Flaherty breaks down the four pillars of IP ownership: trademarks, trade secrets, patents, and (the big story right now), copyrights.

If you were ever confused about the difference between all this stuff, this issue is for you.

You’ll learn:

- What is intellectual property?

- From an economic standpoint, why does IP need to be protected?

- Can you truly “own” an idea?

- What is the point of trademarks? How do they differ from trade secrets?

- How do patents work?

- Can you patent algorithms, music, and art?

- Why do patents only last 20 years?

- What’s the difference between patents and copyrights?

- Why do cartoon mice have longer-lasting IP protection than revolutionary technology? 🎟️

- What role does Disney play in extending copyright law? 🎟️

- Which companies are built on copyright infringement? 🎟️

- Are memes copyright infringement? 🎟️

- Why do some companies decide not to sue? 🎟️

- Can copyright law really kill AI? 🎟️

- Should AI be allowed to train on copyrighted material? 🎟️

- Should AI be allowed to produce copyrighted material? 🎟️

- Is AI licensing the future? 🎟️

- Should companies try to license inputs or outputs? 🎟️

Let’s go 👇

Note: This is a paid edition. To read the full issue you’ll need the All-Access Pass. 🎟️

Table of Contents

What is IP?

Imagine buying a copy of your favorite author’s most recent book.

Although the tangible book itself is your physical property, the story and words that make up the intangible ideas of the book are not. Those are (usually) owned by the author as their intellectual property (IP).

IP ownership comes with some special rules, because intangible goods aren’t scarce in the way tangible goods are.

- Physical property is mutually exclusive. If one person has it, another person doesn’t. If I steal your copy, I’ve deprived you from reading it.

- But if I “steal” a book from you by copying it word for word, I haven’t stopped you from enjoying it. An infinite number of people can simultaneously enjoy an idea without preventing each other from doing so.

In technical economic terms, intellectual property (like the content of books) is called non-rivalrous, since one person’s use doesn’t disrupt another’s.

But while non-rivalrous IP may be true as a theoretical matter, it’s only true as a practical matter if the cost of distributing intellectual property is effectively zero. (Which, thanks to the internet, it is)

And this is exactly why ownership rights still need to be protected: To preserve the economic incentive to create.

Can you really own an idea?

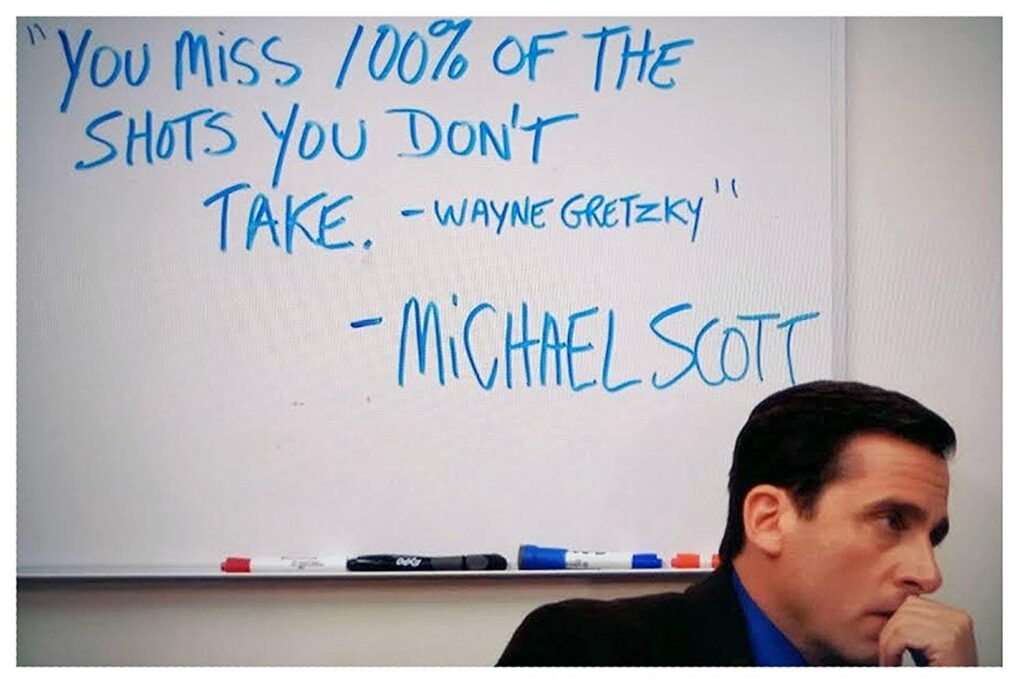

“Good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

– Pablo Picasso (we think)

Society benefits from people coming up with new ideas. But if creators can’t own their creations, they’ll have little incentive to do so.

After all, what’s the point in writing and selling a book if a competitor can copy it and undercut you as soon as it’s released?

There’s a tension here between competing social interests. We know that existing ideas inspire new ideas, and truly fostering creativity means allowing artists and inventors to iterate and transform existing works.

With this balance in mind, most of the world gives creators the following deal:

- You cannot really own an idea, but you can own the expression of an idea. This concept is known as the idea/expression distinction

- You can own expressions, but not forever. Eventually, your ideas go into the public domain for anyone to use.

There are four major types of intellectual property, each with their own set of rules.

Trademarks

Trademarks are a bit of a black sheep in the world of intellectual property. They’re not really justified by the “incentive to innovate” argument we presented.

Instead, trademarks are all about preventing customer confusion.

The general idea is that consumers shouldn’t need to waste their time wondering whether a branded product actually comes from the company they associate with the brand.

Interestingly, knowing that some people will always be confused, early UK case law dictated that trademarks must be unique enough that a ”moron in a hurry” would be misled. (Yes, a real judge wrote that.)

Trademarks can cover some surprising areas, including colors. UPS, for instance, has trademarked its distinct color brown. But as we recently discussed, this doesn’t mean UPS fully “owns” their shade of brown – you can only file trademark infringement cases against companies in the same industry.

And while trademarks can theoretically last forever, you can’t let them wither; they must have continuous use. You need to monitor the marketplace for illicit uses of your brand. And if you fail to defend trademarks in a timely manner, you can lose them.

Trademarked names also risk “generi-cide“, which occurs when a brand name becomes so popular that it starts to refer to not a specific product, but all products in a category.

For example, you may know that Kleenex and Aspirin are trademarked brand names. But did you know about zipper? Or escalator? Or trampoline? Or even kerosene?

Trade secrets

A trade secret is a commercially valuable piece of information that a company doesn’t want its competitors to know.

You don’t need to register trade secrets, but they have legal intellectual property protection.

Companies want to keep an idea a secret, rather than formally register it, because intellectual property protections are usually time-bound.

Patents and copyrights expire, but secrets can be held forever – which is why Coca-Cola opted to keep its famous recipe as a trade secret.

To be clear, trade secret legal protections don’t extend to a competitor reverse engineering or independently discovering the information.

Rather, they deal with cases of theft, like the time a Coke employee tried to sell trade secrets to Pepsi (who went straight to the FBI).

Patents

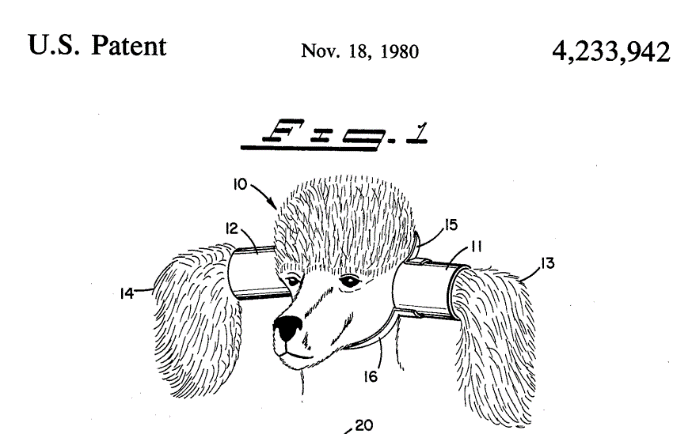

A patent offers creators the exclusive rights to an invention, usually for a maximum of 20 years.

During that time, no one else can use the invention without sign-off from the patent owner (although some countries have some exceptions for private or non-commercial use).

Not everything can be patented. Notable exclusions include scientific discoveries, laws of nature, and mathematical formulas.

What about algorithms?

Algorithms are generally fair game.

For instance, Google was able to patent its famous PageRank algorithm since it demonstrated a novel, practical application of mathematical techniques.

But the line can get confusing. Courts in the US have become much more skeptical about accepting patents for computer programs in recent years since they don’t want code to be a patentable “wrapper” around fundamentally non-patentable ideas.

What about music and art?

You also can’t patent music and other forms of art.

To protect those creations, you’ll need the fourth type of IP…

Why do patents only last 20 years?

Patents are usually based on technological innovation, which often becomes moot after 20 years.

This is probably the biggest reason there’s not big push to extend patents; you just can’t “milk them” as long as copyrights because, better tech is always being made.

The Empire Strikes Back (1980) is a great movie, but I wouldn’t want to drive a car made that same year. Etc.

Copyright

Similar to patents, copyright offers creators exclusive rights to their work. But instead of inventions, copyright covers literary and artistic works – including, curiously, computer programs.

If programming is already protected by copyright, why would you want to patent it?

Because patenting provides broader IP ownership than copyright. Remember, with a patent you can protect not just the specific program, but the idea as a whole.

While broader protection is one advantage of patents, copyright protection has some surprising benefits that patent protection lacks.

Copyright is automatic

Copyright exists at the moment of creation.

Unlike with a patent, you don’t need to register your work to earn copyright protection. It’s self-evident and instantaneous.

For example, this issue (and every word we have ever published), is automatically protected by copyright.

However, you will usually need to register a copyright before you can file an infringement case (that is, if you want to win).

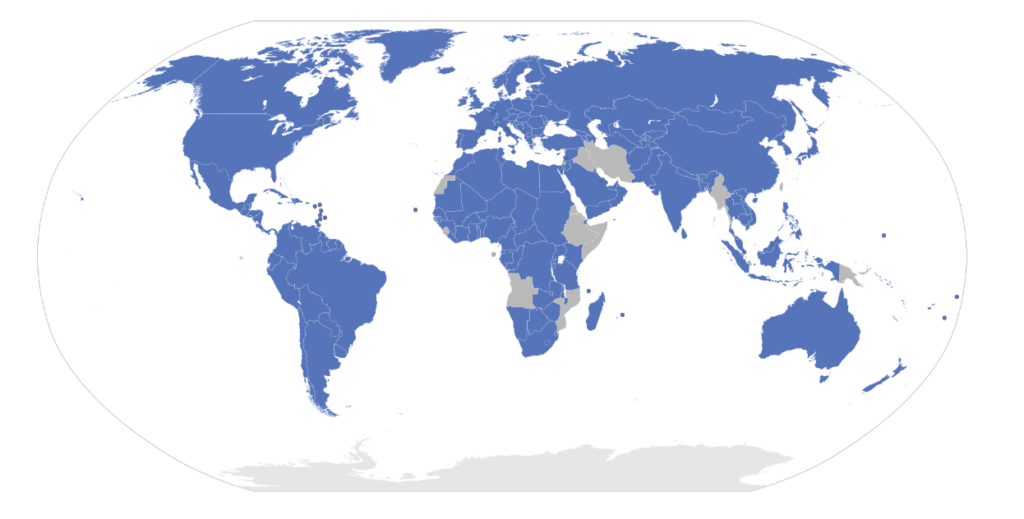

Copyright is global (mostly)

Even better, while patents need to be registered independently in every territory you want protection in, copyright protection spans almost the entire globe.

To illustrate how powerful copyright is, if you write a book in Mexico, you’re instantly granted similar IP protection in countries as far afield as Vietnam and South Africa.

Now, keep in mind that protection is only worth something if it can be enforced — and filing an infringement suit in a foreign court can be ridiculously complex and costly.

Let’s say someone in Russia uses your work. Sure, you can send a cease and desist to someone in Russia, and threaten to sue them. But it’s not like they’re gonna listen. So your next step is filing an infringement case in Russian courts. Not exactly an easy task.

And that’s a country that respects the Berne Convention. What if it’s someone in Iran? Then it’s anything goes. Generally foreign copyright is not respected whatsoever. So, yeah. Good luck!

Copyright lasts much longer

Finally, copyright lasts much longer than patent protection. While patents expire after 20 years, copyright protection can easily last more than a century.

- In the US, copyright for individually produced works lasts for the life of the creator plus 70 years

- For works owned by an employer, protection lasts 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation — whichever comes first.

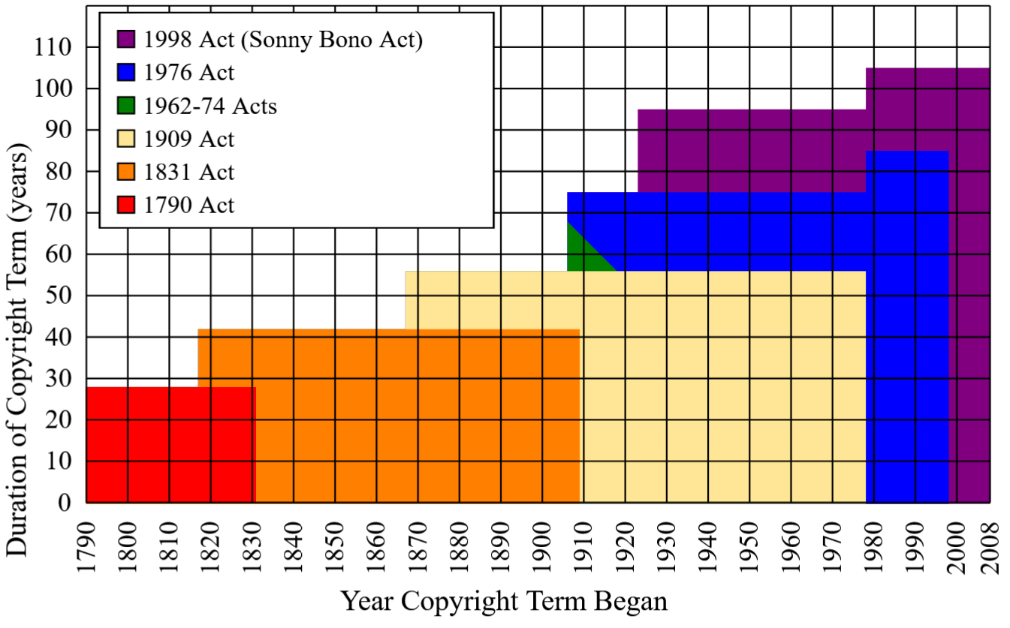

But it wasn’t always this way – originally, copyright length was almost as limited as patent length.

So how did we get to the point where cartoon characters have longer-lasting IP protection than revolutionary technologies and life-saving drugs?

Why does copyright last so long?

It used to be just 28 years..

Modern copyright law started in 1710 when the British parliament passed the Statute of Anne.

The Statute codified three key principles which are now commonplace:

- The government and courts should regulate copyright, not a private company.

- The creator of a work should own the rights to it, not the publisher.

- Copyright should have a limited life. It should not last forever.

The Statute prescribed a copyright length of 14 years, with renewal for a second 14-year term if the author was still alive at the end of the first.

As such, the maximum time copyright could last was 28 years – quaint by modern standards.

Inspired by the statute, a young America passed its own copyright law in 1790, which also established a contingent 28-year term (although international copyright wasn’t exactly respected in the new country, much to the fury of Charles Dickens.)

..until corporate lobbyists got involved

Over time, Congress has continuously extended the original 28-year copyright term.

Unsurprisingly, each new piece of legislation has been strongly supported by political parties who benefit from longer copyright protection.

- In 1831, copyright was extended to a maximum of 42 years on the back of lobbying efforts by author Noah Webster (of dictionary fame).

- In 1909, on his last day as president, Theodore Roosevelt signed into a law an act extending maximum copyright to 56 years. Teddy authored 30+ books, and was a strong supporter of copyright laws.

- Then, amid significant lobbying efforts from Disney, copyright was extended again in 1976. Passed eight years before Mickey Mouse was set to go into the public domain, this act created a 75-year term for works made for hire, and life + 50 years for individual works.

- Most recently, in 1998, further lobbying by Disney led to the current iteration of American copyright laws: life + 70 for individual works and 95 or 120 years for corporate ones.

The act is sometimes derisively called the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act”, but other major lobbyists included Time Warner, Universal, and Viacom.

Disney’s role in copyright law

Today, the corporate push for greater copyright terms is likely dead.

The political environment has shifted greatly, and awareness of copyright issues has led to public pushback. Truth be told, The Mickey Mouse Act may be Disney’s last copyright hurrah.

To be fair, advocates of the Mickey Mouse Act point out that the US was merely catching up to international standards. At the time, European copyright lasted 20 years longer than America, which made American works less competitive under international rules.

Still, Disney’s support for legislation that keeps their creations out of the public domain is undeniable. And it’s especially hypocritical, since Disney has made liberal use of the public domain in their own work!

Among other examples, the original Alice in Wonderland, Pinocchio, and Snow White stories’ copyrights had expired by the time Disney made their famous film versions.

(Our friend Trung Phan just published a great list of Disney’s public domain usage)

Still, Disney isn’t able to outrun copyright forever. Earlier this year, an early version of Mickey (i.e., “Steamboat Willie“) entered the public domain for the first time.

Be careful, though. Disney still has a trademark on Mickey Mouse, and the extent to which the firm can use that to police the character’s commercial use is still up in the air.

Disney is indicative of the way companies seek to exploit copyright law to protect their profits, but not all firms are interested in following the rules.

In fact, some mainstream business models actually seem to be built entirely on mass copyright infringement…!

Which companies are built on copyright infringement?