Today, we’re looking at In-Q-Tel, the secretive firm funding some of America’s leading tech companies, operated by none other than the CIA.

It’s surprising that more people don’t know about this company. But it’s not like their returns have been noticeable.

In fact, unlike every other VC in the world, In-Q-Tel seems profoundly uninterested in turning a profit…

This is a fantastic issue.

You’ll learn:

- What are Silicon Valley’s national security roots?

- What military products did Silicon Valley use to build?

- What was Silicon Valley’s first IPO?

- Why did the end of the Cold War lead the CIA into venture capital?

- How did In-Q-Tel get started?

- Why does In-Q-Tel not care about turning a profit?

- Is In-Q-Tel really a VC after all?

- 🎟️ What does In-Q-Tel invest in?

- 🎟️ What size checks do they write?

- 🎟️ What explains In-Q-Tel’s poor financial performance?

- 🎟️ What are some famous companies backed by In-Q-Tel?

- 🎟️ What is In-Q-Tel’s greatest success story?

- 🎟️ Why startups might not want to take CIA money?

- 🎟️ What are some of their current secret investments? (← Crazy stuff in here!)

Let’s go 👇

Note: This issue isn’t sponsored by anyone. But to read the whole thing you’ll need the All-Access Pass. 🎟️

Table of Contents

The CIA’s secretive venture capital fund

As America’s top intelligence service, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) keeps busy with everything you’d expect from a spy agency — covert operations, information analysis, cyber warfare, all that fun stuff.

But the agency also has a little side gig you may not know about. They’re a venture capitalist for some of America’s leading tech companies.

Through In-Q-Tel, the CIA provides early-stage equity funding to companies building technology that might prove useful to intelligence agencies.

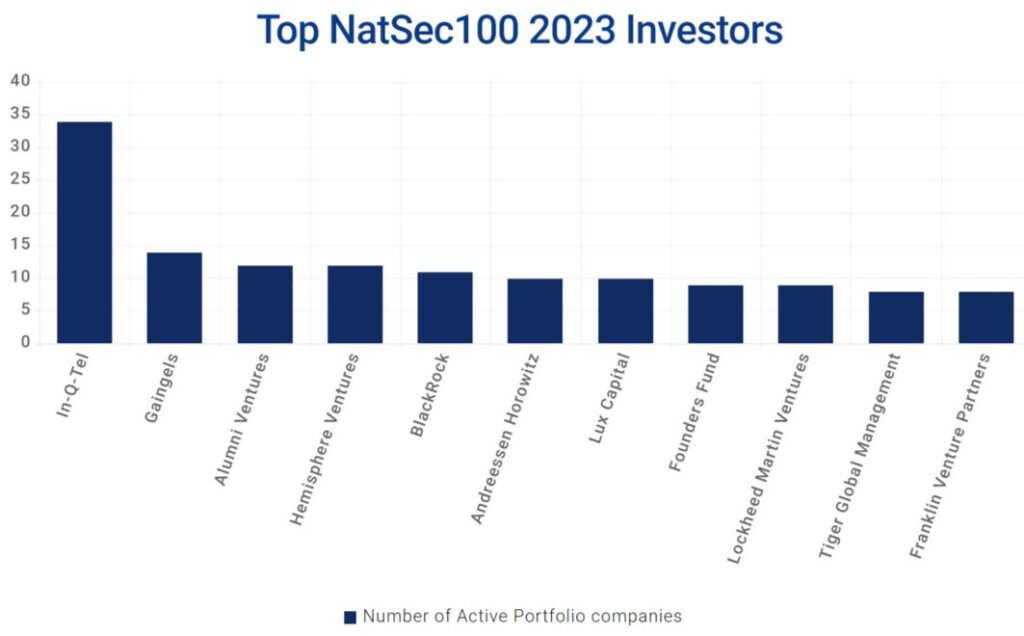

To date, In-Q-Tel has invested over 700 companies, by far one of the most active VCs in the defense and intelligence space.

And, true to form, many of its investments are never even made public.

While CIA money influencing commercial technological innovation has proven controversial, this relationship is not as out of place as it first seems.

In fact, a big reason Silicon Valley even got started was to serve the needs of the intelligence and defense communities.

Silicon Valley’s origins are in national security

Over the past few decades, tech companies have focused almost exclusively on consumer tech. But it wasn’t always this way.

Back in Silicon Valley’s early days, the government was the main customer for emerging technology (and in many cases, the only customer).

During World War II, Fred Terman (often called the “Father of Silicon Valley“) saw the possibilities afforded by defense spending while working on radio research at Harvard.

After the war he returned to Stanford, bringing with him 11 research students, and a determination to win government contracts.

Building out the university’s practical research capabilities, Stanford became a hotbed of defense research during the Korean War.

That influence also spread to the private companies springing up in the area:

- Varian went public in 1956 in Silicon Valley’s first IPO. The firm’s main business was selling military microwave tubes.

- In the 1960s, the Pentagon accounted for 80% of Fairchild Semiconductor’s revenue. Fairchild’s research eventually spawned the creation of Intel.

- Lockheed’s Silicon Valley campus at Sunnyvale grew to 28,000 employees in 1965, making it the valley’s largest employer. They company was entirely focused on creating military rockets and government spy satellites.

In perhaps the most poetic example of how government contracts helped kickstart Silicon Valley’s tech scene, Steve Wozniak (Apple’s co-founder) is the son of a Lockheed engineer who worked at the Sunnyvale facility.

Silicon Valley wasn’t suited for contracting

This model continued throughout the Cold War, with government contracts providing the money for private companies and research institutions to pursue technological innovation.

The CIA itself made ample use of contracting, with the U-2 spy plane, SR-71 “Blackbird,” and CORONA surveillance satellites all created in coordination with Lockheed.

The Cold War fueled defense spending from the ’60s through the ’80s. But once the USSR fell in the 90s, defense spending dried up, and the contracting model became unworkable.

And we all know, in the late 90s the dotcom boom got underway.

- The decline in defense spending meant that the government could no longer foot the bill of technological innovation entirely.

- Technological innovation began to shift to startups pursuing market commercialization, rather than large firms operating on government contracts.

- Startups that were used to rapid adoption and iteration were entirely incompatible with slow government procurement processes.

The motivation to develop an alternative funding model was perhaps strongest at the CIA. As the digital world became an increasing part of intelligence work, the agency risked getting left behind without access to private sector innovation.

So, the CIA embraced a funding model more amenable to the growing tech sector: venture capital.

In-Q-Tel’s early days

The roots of In-Q-Tel can be traced to the 90s, when CIA director George Tenet advocated for a market-based solution to bridge the gap between the agency’s capabilities and commercial technology.

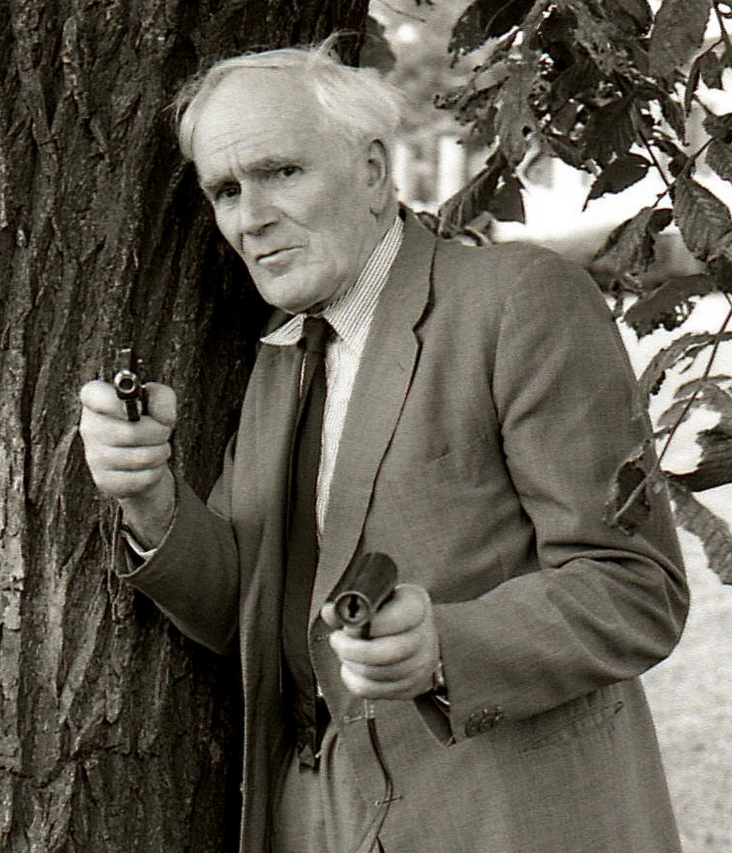

Showcasing the transition between funding models, Tenet recruited two businessmen with entirely different backgrounds to run the new firm:

Norm Augustine, who had previously served as the CEO of Lockheed Martin,

And Gilman Louie, who got rich starting a video game company as a college dropout.

In its earliest iteration, the CIA’s VC arm was called ”Peleus”, named after the mythological hero who fathered the greatest Greek warrior, Achilles.

But the firm eventually became known as In-Q-Tel, a nod to the fictional MI6 quartermaster who supplies James Bond with his high-tech gadgets.

By 1999, In-Q-Tel was up and running as the CIA’s new experimental funding model, with a structure that’s as weird as you’d expect from a government-linked venture capital firm.

In-Q-Tel’s unique structure

In-Q-Tel isn’t technically a division of the CIA.

Instead, it’s a separate not-for-profit company incorporated in Delaware that’s bound to the agency by a special charter.

As demonstrated by its not-for-profit status, In-Q-Tel’s mission is not to make money for the CIA. Rather, the firm is directed to

“…identify and deliver cutting edge technologies to the US intelligence community.”

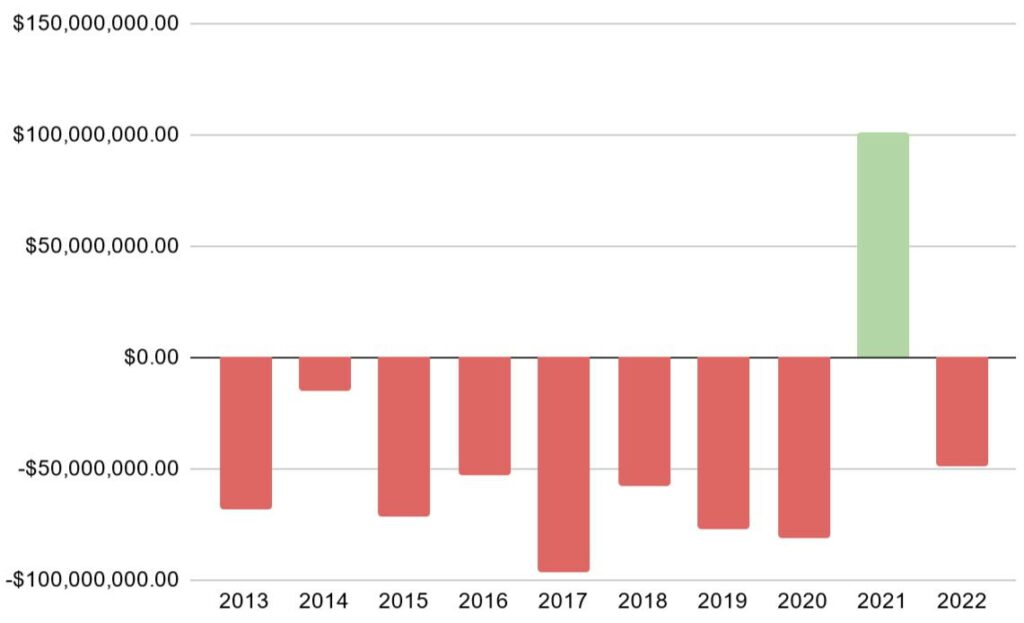

In fact, unlike every other VC in the world, In-Q-Tel seems profoundly uninterested in turning a profit.

On an internalized basis, the firm has posted losses in 9 of the past 10 years, with 2021’s shortfall amounting to nearly $50 million.

But In-Q-Tel still has plenty of money to invest, largely because the CIA pumps tons of money into the firm.

From 2017 to 2021, total government contributions to In-Q-Tel amounted to nearly $500 million.

Although the firm is unable to pay the bills without CIA help, In-Q-Tel’s assets have grown to more than $1 billion. Sure, this is small compared to VC giants like Sequoia (~$100 billion in assets), but still large enough to have real influence.

Given these figures, it’s worth considering whether In-Q-Tel is really a venture capital firm at all.

Is In-Q-Tel really a VC firm?

If In-Q-Tel doesn’t actually make money, it looks more like a subsidy program for technology useful to intelligence agencies.

One way of understanding In-Q-Tel is as a technology vetting service for other VCs.

If In-Q-Tel invests in a company, chances are that the underlying technology is both legitimate and useful, drawing in more investors and catalyzing further development. In fact, In-Q-Tel brags that each dollar they invest creates $28 in private sector investment.

Whatever the case, it’s clear that In-Q-Tel’s work has promoted the development of some very useful technologies — including some you probably use daily.

In-Q-Tel’s Portfolio: What Does the CIA Invest In?