Today we’re taking another look at airspace rights — the complex web at the intersection of private property ownership, logistics, and regulation (not to mention a burgeoning new asset class.)

This week’s issue is timely — yesterday a Chinese spy balloon was shot down over the US. But that happened at an altitude of about 60,000 feet. Way up in the sky. The type of airspace rights we’re talking about today takes place 100x closer to earth.

A decade ago, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos did a famous 60 Minutes interview where he introduced “Amazon Prime Air”: The revolutionary technology where Amazon would use drones to deliver packages to your house in under a half hour.

Yet, ten years later, instead of being widespread, drone delivery is almost nonexistent. The technology certainly exists, but the industry seems stalled at best, and overhyped at worst.

So what happened here?

Let’s go beyond the hype to understand what’s holding the industry back, and where we go from here. This is Part 2 in our ongoing series on airspace rights. (For a quick primer, here’s Part 1)

This issue features insightful commentary from Jonathan Dockrell of Skytrade Links — one of the most forward-thinking companies in the (air)space.

Table of Contents

Jeff Bezos’s false promise

You gotta hand it to Bezos — the guy knows how to build hype. It’s impossible to watch Amazon’s promo video and not get a bit excited:

Drones carrying packages that land in your backyard. Instant delivery of toys, groceries, and medicine. Are you kidding? Epic!

According to Bezos, there would be a “fleet of shipping drones taking the sky, as soon as Amazon can work out the regulations.” (You know, just a minor roadblock.)

Many of us thought this reality would only take a year or two. Yet a decade later, Amazon has made a grand total of just 7 home deliveries. Seven!

Who are the big drone delivery companies?

Thankfully, Amazon isn’t the only player here. And they’re not the biggest, either. Far from it.

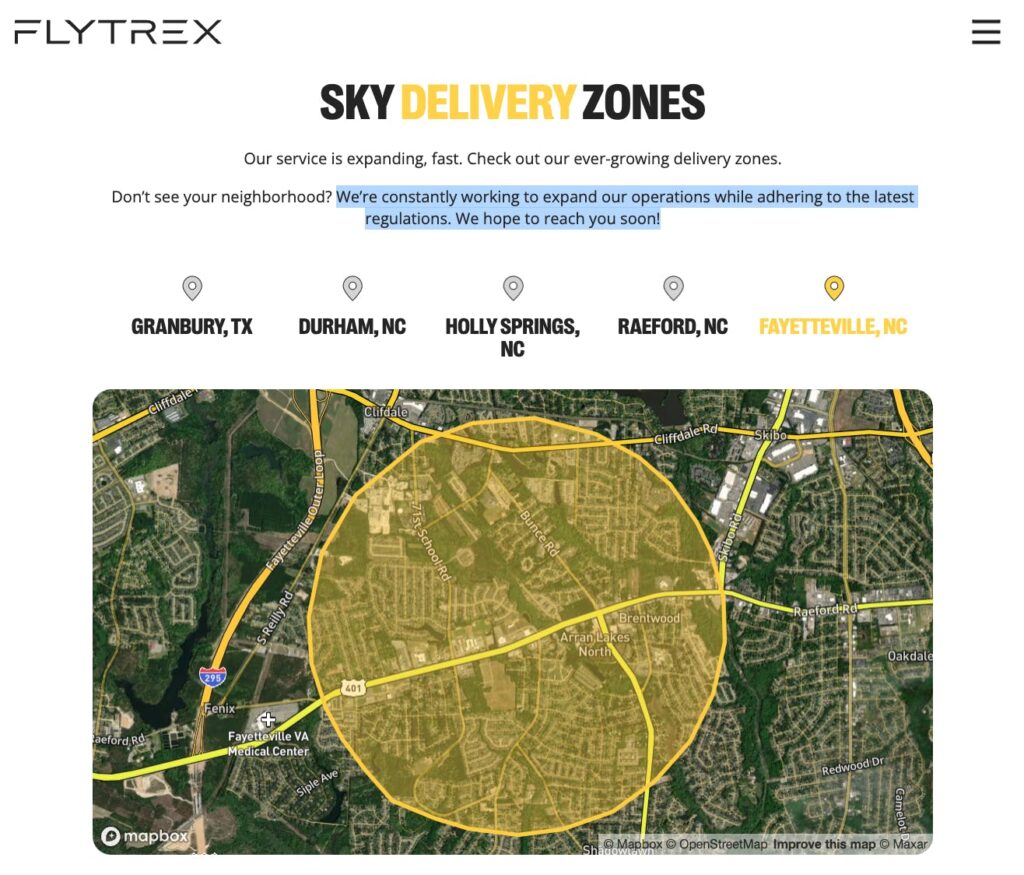

Flytrex

Flytrex promises “instant meal deliveries from the sky!” but is only available in five small suburban locations — four in rural North Carolina.

Zipline

Zipline is also focused on lifesaving medical logistics, and has completed 100,000 commercial deliveries. With HQ in San Francisco, Zipline’s objective is to provide every human on the planet with immediate access to critical medical supplies through drones.

Swoop Aero

Swoop Aero, founded in 2017 (a child in the space), has also focused on medical transport; creating airspace infrastructure and delivering vaccines to the island nation of Vanuatu.

The Military

But because it’s a government organization, the US Army doesn’t have to follow the same rules as private companies. Militaries routinely use drones to move ammo, medical supplies, and other small equipment.

Wing

Wing, owned by Alphabet, is the world leader in private drone delivery. Founded eleven years ago, it completed its first delivery in 2014, and has since focused its operations in Australia.

They’ve now crossed 250,000 deliveries, thanks to a partnership with grocery giant Coles (and now DoorDash.) But it’s still a very limited pilot program that’s only available with certain items in a few select areas.

The private landscape is littered with failed attempts and corpses of companies that went nowhere. For example, back in 2013 the team at Zookal aimed to deliver textbooks via drone, but now appear to have completely given up on that dream.

And it’s no wonder why: This stuff is very complicated.

The problem with drone delivery is airspace rights

Technology isn’t the problem here. That’s easy. That’s been done.

The problem is airspace rights.

It works like this — basically, everything above 600 feet in the air is owned by governments. This is where your commercial vehicles operate. Airplanes, helicopters, etc. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has the authority to regulate air traffic, and impose all sorts of restrictions and requirements on aircraft, such as type, speed limits, routes, etc.

Airplanes soaring above your property are not trespassing, because they are flying in what Congress has declared as a sort of public highway.

But the airspace below 600 feet isn’t owned or regulated by the government. Nope, in most of the developed world, this space is owned by landowners.

And this is exactly the airspace where most of the new air services are trying to operate:

- Food delivery (drones)

- Cargo deliveries

- Air taxis (passenger drones)

- Other UAVs

See, these companies are trying to work with local governments to get their robots into the sky. But guess what? In almost all cases, it isn’t something the local government can approve.

In America, the FAA states that drones cannot fly over roads, habitats, or people without case-by-case permission. Think about that for a minute: Between a warehouse and a drop-off location, there could be hundreds to thousands of unique air rights that drones would need to pass through. All of this property is owned by landowners, and each need to give approval, every time.

Oh, and to make things even more complex, local and federal governments often disagree on how air rights are regulated. At the local level, governments can guide landowners and drone companies, but they cannot easily adjust zoning regulations to control air space above private land (or even public land!)

In July 2022, College Station, Texas made news when City Council approved a zoning change allowing Amazon to create a Prime Air facility; one of just two “home bases” in the entire country (the other is in Lockeford, CA).

Great news! But this is just a building we’re talking about. The city of College Station still has no ability to regulate drones, so only a select few Amazon customers within a meager 4-mile radius can place orders.

See, this is all being done on a city-by-city basis. This isn’t like Uber, who “blitzscaled” their way into new cities and quietly disrupted taxis before regulators could catch up. This is airspace we’re talking about here. Everyone notices this stuff. You can’t just enter a city without permission and fly under the radar.

In typical fasion, Amazon isn’t even getting permission from homeowners. That’s part of the problem. They are getting very limited permission to fly under something called Part 135 which has no regard for property rights. They are trying to “land-grab” and ignore what property owners don’t even know they own.

And because there’s no overarching protocol for how air paths can be formed and used, the industry is moving much slower than people expect.

To extend the automobile metaphor: There are no traffic lights. 🚦

Regulatory uncertainty

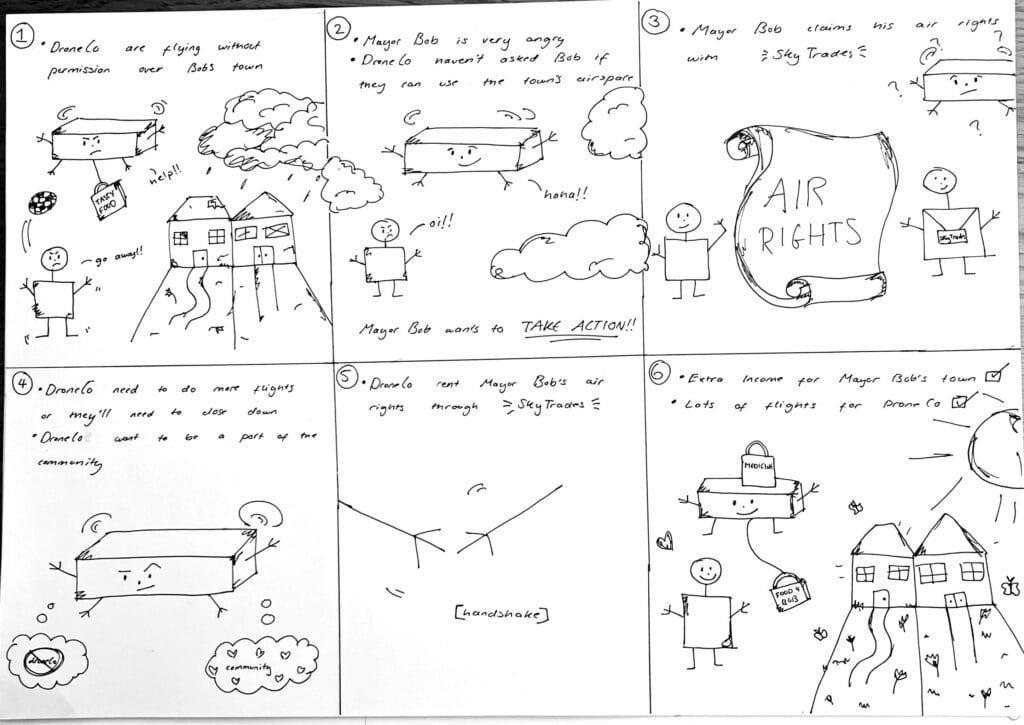

Jonathan Dockrell is the founder of a company called Skytrade Links. And he’s trying to change all this.

Jonathan recently began writing a Substack called Where’s my flying car?, a tongue-in-cheek play on Peter Thiel’s famously snarky line about hardware innovation, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

In a recent post, Jonathan made a simple but powerful statement: Traffic lights speed us up.

Before we had traffic lights, roads were managed by local police, who stopped traffic with hand gestures and flags before directing cars across 4-way intersections. (It turns out that roundabouts are superior, but we’ll save that for another issue).

The first traffic signal was developed in London in 1868, but the design didn’t last. Eventually we adopted the universal three signal standard we all know today.

What happened when we did this?

That’s right. We got more cars.

Skytrade: A new protocol for airspace rights

This is where companies like Skytrade come in.

You can build all the trains you want, but they can’t go anywhere unless they have established, well-maintained tracks.

Skytrade wants to lay down train tracks for the sky; to establish invisible “airspace rails” in a global, liquid marketplace for airspace rights.

If that sounds daunting, well, it is. But there are two steps to making this a reality:

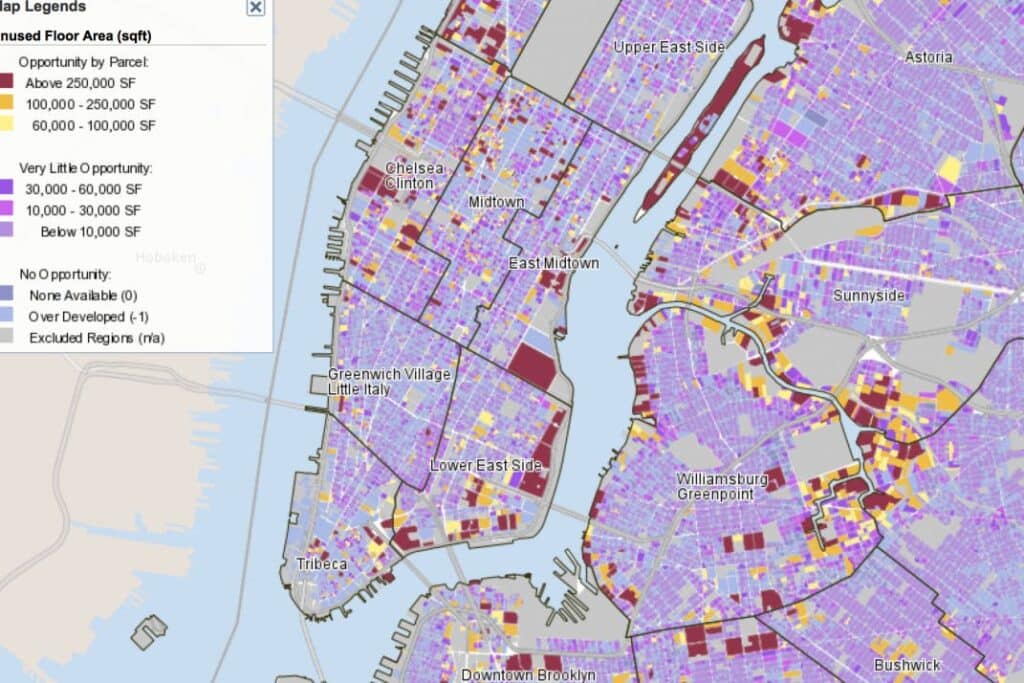

First, you need to get municipalities and local governments involved. Since roads and highways are already owned by these bodies, they own the airspace above them (up to 600m).

This means that drones could theoretically fly directly above roads and avoid the air rights issue altogether. Boom! Instant drone highways.

But drone highways only get you so far. Nobody lives on a highway. What happens when the drone needs to “exit” and drop a package off at a house or business?

That’s right, you have to cross over private land. And remember, you need explicit permission to fly over people’s homes!

So, the second step is to create exactly this. ☝️

That’s right, Dockrell wants to create the world’s first public air rights marketplace.

This is a place for landowners to claim their air rights, register them, and monetize the air space above their property. They’d be selling to drone companies (or perhaps even air space distributors) to create drone corridors that link to highways. 🤯

The idea is that this will create “private air pockets” which drones and air taxis could use to travel to specific places.

To further illustrate the dawn of this new alternative asset class, have a look at these drawings by Dockrell’s daughter:

What does the future look like for air rights? (for real)

If this model becomes reality, it could end up looking a lot like rivers.

Just like water, drones and air taxis would stick to “desired paths of least resistance” — the most efficient, legal route to get from point A to B.

This modified hub-and-spoke model makes perfect sense for companies like Amazon that can afford to set up micro-distribution centers. Not relying on roads for deliveries could save companies a ton on fuel and employee wages. The idea is these new drone takeoff points would handle all “last mile delivery” (i.e., delivering directly to homes).

But this model won’t work for everyone. Some people don’t want drones anywhere near their homes, kids, or even pets. And that’s okay! This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Drones could simply flow around them. (Remember, landowners only own the space directly above their property, and everyone is essentially “opt-out” by default).

Yes, air NIMBYism will someday be a thing. But this would create extra demand, possibly pushing returns upward for homeowners who do choose to monetize.

Regardless, Skytrade’s goal is to connect willing landowners with drone companies looking for a delivery path; to create permissioned “tributaries” that legally flow across private land to allow for door-to-door drop-offs.

Drone and air taxi operators could pay a commission when using certain “airborne tollways”. This excess would trickle down to the consumer, and ultimately make its way to the air rights owner. Certain pathways could cost more during peak hours. Or drones could take a slower, less popular route, in order to save money.

Drone corridors won’t be a chaotic free-for-all; the key here is creating fully-permissioned routes.

Closing thoughts

Air rights is one of those topics not enough people are talking about. (Heck, we’ve only written one previous issue on the topic, and we already rank 10th for the term.)

But this won’t be the last time, either. I believe the hype is very real. But so is the elephant in the room. This stuff won’t just start happening on its own. The bottleneck is regulation. Period.

If it wasn’t already clear with crypto, it should be clear now: regulation provides confidence and clarity. And the entire industry desperately needs a clear path forward — especially in the US.

This isn’t necessarily the FAA’s fault. Remember they don’t own airspace below 600 feet. So they’re punting the problem over to the local communities, which don’t have any tools to deal with it! It’s like, “Hey guys, all these battles are about to start happening. Here’s a stick.”

To be clear, the public concerns are very real. Not everyone likes this technology! Drones sound like a chainsaw and can be a distracting eyesore. Humans aren’t generally fans of things that fly near their heads (bees, flies, etc). Animals seem to dislike them as well.

But if done properly, airspace markets could forever revolutionize low airspace travel. Air rights could resemble spectrum auctions in the 1980s; an appreciating asset that could be bought, subleased, traded, and borrowed against – if it were only permitted.

In some ways, air rights should be easier for humans to solve than roads & traffic signals were. Very little physical infrastructure is needed here. Unlike land, air is everywhere. And unlike with driving, you wouldn’t necessarily need global standards. It’s not like you’re traveling long distances here. Packages aren’t going from country to country. Local rules should suffice.

There’s a risk that making air routes as fungible as real estate opens it up to “tragedy of the commons” problems. While it’s easy to imagine air corridors, it’s also easy to imagine one company owning a critical chokepoint air route that all drones must pass through. Sort of like a toll-extracting fiefdom, creating a new tax everyone must pay.

But we’re a long way off from drone delivery turning into some dystopian corporate nightmare. The hype is over, it’s time to get real.

If we want to make this stuff a reality, we have to develop the traffic lights. We have to fight for it.

Just remember, nature fights back. (Especially here in Australia!)

Further Reading

- Jonathan Dockrell’s Substack

- A Risk-Based Approach: The UAS BLVOS Arc Final Report

- Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology

Disclosures

- This issue may contain affiliate links.

- This issue was not sponsored by Skytrade in any way. I just love the company.

- We have no air rights in our ALTS 1 Fund, because there’s no market for it. (As soon as one opens up, we’ll be all over it)