Today, we explore Brightline: The only privately-owned and operated intercity railroad in the United States (and the first train line the US has launched in over a century).

Note: This issue isn’t sponsored by anyone. But to read the full thing you’ll need the All-Access Pass. 🎟️

Table of Contents

What is Brightline?

For decades, America has been great at building software infrastructure. Terrific, even. Unmatched in the world.

But physical infrastructure has been another story.

In fact, America hasn’t had any private intercity rail service since 1983, when the Rio Grande Zephyr between Colorado and Utah shut down its service for good.

While the project has had a few hiccups, Brightline has already achieved some major milestones in its quest to provide modern passenger rail to the state of Florida.

Last year marked the completion of Brightline’s long-awaited Miami to Orlando route. And the firm has already announced plans to extend the line to Tampa by 2028.

Brightline isn’t your average commuter train. It boasts a maximum speed of 125 mph — well above the 110 mph limit of most US intercity trains.

That’s certainly inspiring to lovers of high-speed rail, who have been begging for a system in America for decades. But it’s still far behind countries like Japan, with its world-famous bullet trains.

America hasn’t always lagged western countries in rail though.

For example, in 1869 America built the first transcontinental railroad, which helped accelerate the rapid industrialization of the western states.

And at its peak, the Pennsylvania Railroad was the largest transportation network in the world.

So why has America fallen so far behind in passenger trains? And what can Brightline teach us about the future of high-speed rail in the country?

Why does America struggle to build high-speed rail?

First we need to define high-speed.

As a general rule, trains with a top speed of 155 mph are considered “high speed.” (That’s the definition used by the International Union of Railways. The EU seems to agree.)

By this definition, Brightline doesn’t actually count as real high-speed rail.

Instead, it falls under what the US Congressional Research Service generously calls “higher-speed rail.” Good for marketing, but not quite the real thing.

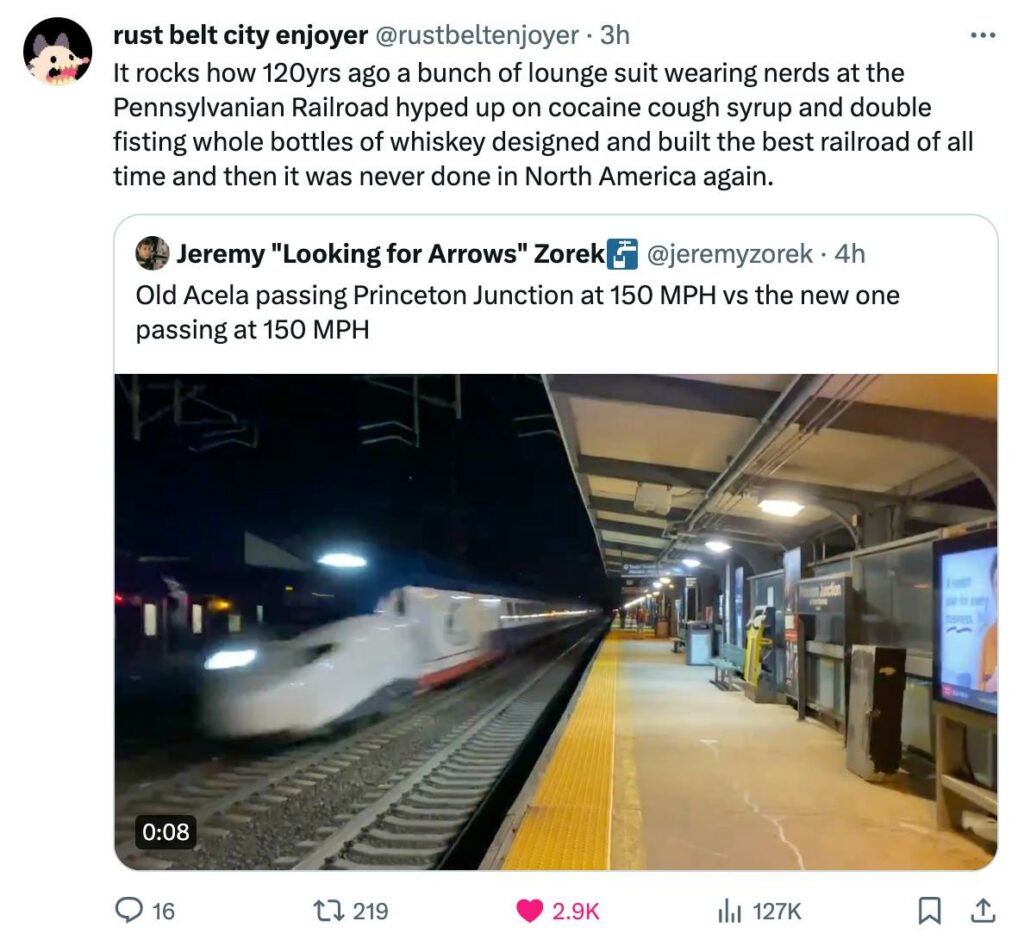

Amtrak’s Acela line is the fastest train in the US, but even that doesn’t make the high-speed cutoff, because it tops out at 150 mph.

(That will actually change this year with new Acela trains hitting 160 mph, giving America its first true high-speed rail).

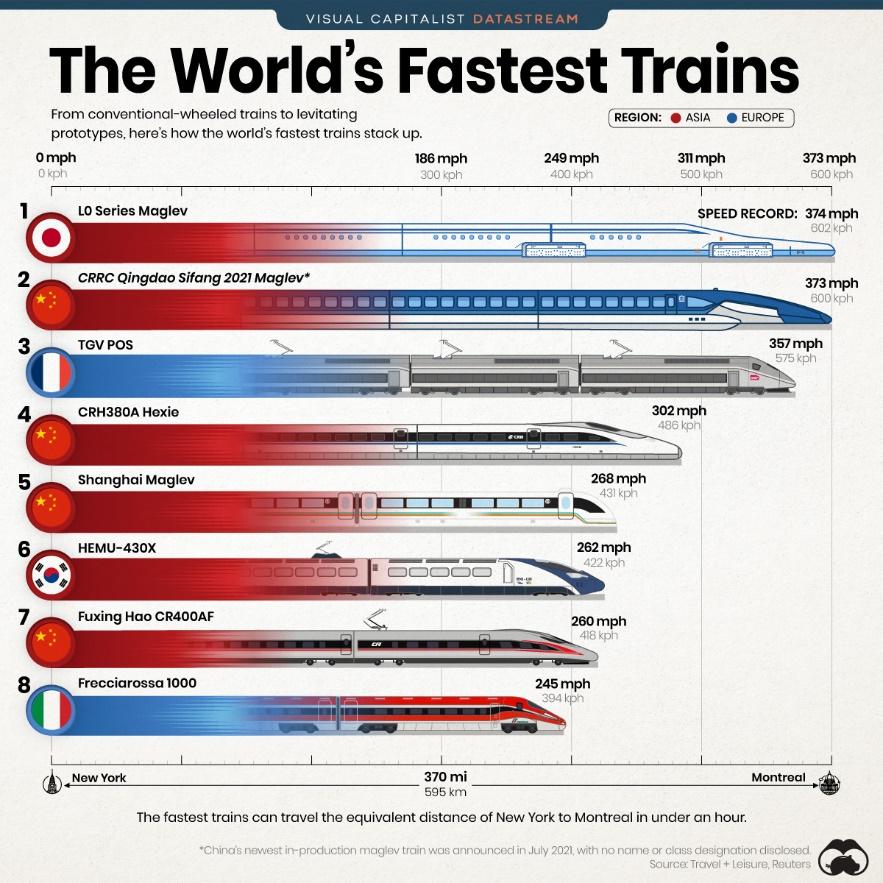

Meanwhile, world-leading trains in Asia and Europe are racing ahead:

The reason America’s trains lag has nothing to do with technology. We know how to build stuff that goes fast.

It has to do with demographics and economics.

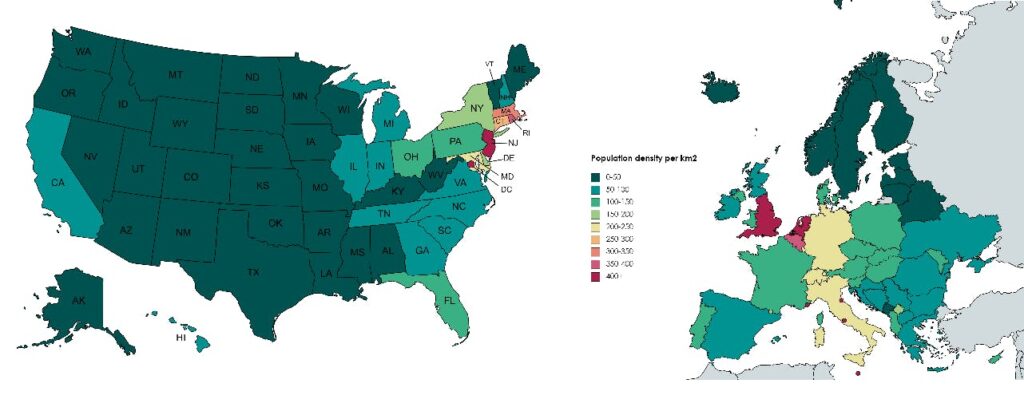

America has low population density

The most important factor in whether to invest in intercity rail is population density.

Passenger rail makes the most economic sense when populations are dense enough to coalesce around a few key stations and lines.

Intercity train lines are hugely expensive to build (Brightline’s six-station Florida line cost $6 billion) and they take up a ton of space.

In effect, much (though not all) of America has terrible demographics for passenger rail.

Lower population density makes flying a more attractive option for traveling between far-flung cities — even after accounting for time spent getting to the airport and waiting in security lines.

Population density is the main reason that Europe has such an expansive passenger rail system and America doesn’t. That’s the economic reality.

And while the lovely walkability of European cities has become a meme, it makes an appreciable difference in easy access to major rail stations — compared with driving or renting a car, which both incur extra costs (like transportation, parking, and time)

Finally, the average distance between American cities is larger than Europe, meaning flying is often the most efficient long-distance travel option.

(Incidentally, Australia suffers from similar density issues, which is probably why high-speed rail down under has been stuck for 40 years.)

The car dependency feedback loop

Of course, America’s low population density also ties directly into the country’s car-dependent culture.

Car dependency and low density are stuck in a feedback loop. Prioritizing car-based transportation infrastructure promotes low-density living, as low-density living increases the need for car ownership.

As car ownership increases, passenger rail becomes less of a priority for lawmakers, due to low perceived need. And round and round we go…

Yes, gridlock and traffic from too many cars causes frustration, and can help reverse this trend. But historically it’s been a very tough cycle to break. America has shown it would spend less upfront to add another lane to a freeway, than invest in a long-term rail megaproject.

Passenger rail requires subsidies (usually)

Even in a nice dense area like Europe, it’s extremely challenging to make the economics of passenger rail work on their own.

The Europeans know that passenger rail service requires tremendous upfront and operating costs. This is why the European industry relies so heavily on state subsidies.

The flagship rail companies of Spain (Renfe), France (SNCF), and Italy (Trenitalia) aren’t even private ventures. Instead, they’re state-owned.

In 2018 alone, Germany spent $13 billion in rail subsidies –— over twice the cost of building the entire Brightline Florida line from scratch!

On top of that, many European countries are experimenting with demand-side subsidies, offering discounted or even free tickets.

Even if an intercity rail system isn’t profitable on its own, there are valid economic reasons a government might still support one:

- Labor flexibility. Making it easier for workers to commute

- Economic activity. Making it easier for tourists and residents to reach amenities & shopping destinations

- Decreased pollution thanks to fewer cars on the road

But with America’s penchant for privatization, garnering the political will for a new state-subsidized rail program isn’t exactly an easy sell — especially because one already exists!

Amtrak, America’s national passenger railroad company, was launched in 1971 with the goal of eventually becoming a self-sustaining business.

But so far, the company has been unable to turn a profit in its entire history, and has resigned itself to becoming a state-supported venture (and frequent political punching bag).

Why is American infrastructure so expensive to build?

Clearly, making passenger rail profitable is challenging enough on its own. But it’s especially hard in America because of the disproportionally high infrastructure costs.

Tunnel projects always seem to cost more in America. In just one example, building a tunnel in New York cost $1.5 billion per mile in 2015, compared with $327 million per mile in Berlin in 2009. Nearly 5x more!

But why?

One possibility for America’s high infrastructure costs is something called Baumol’s cost disease.

The general idea here is that in a growing economy, wages tend to go up, even for sectors that have experienced no productivity growth. This results in higher production costs for those industries.

Due to Baumol’s cost disease (and America’s notably high wages in comparison to other developed countries) American construction labor isn’t much more efficient, but costs a lot more.

There could be other contributors to America’s elevated infrastructure costs, possibly including higher levels of graft & corruption.

But despite America’s economic and political challenges, all hope is not lost for US rail infrastructure.

One country in particular has demonstrated that it is entirely possible to have a profitable high-speed passenger rail network – Japan. 🇯🇵

What can we learn from Japan’s private rail system?

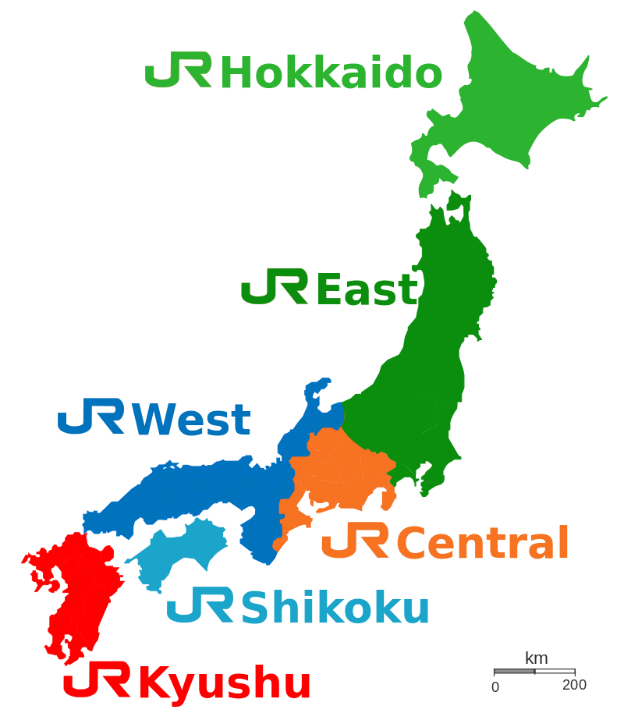

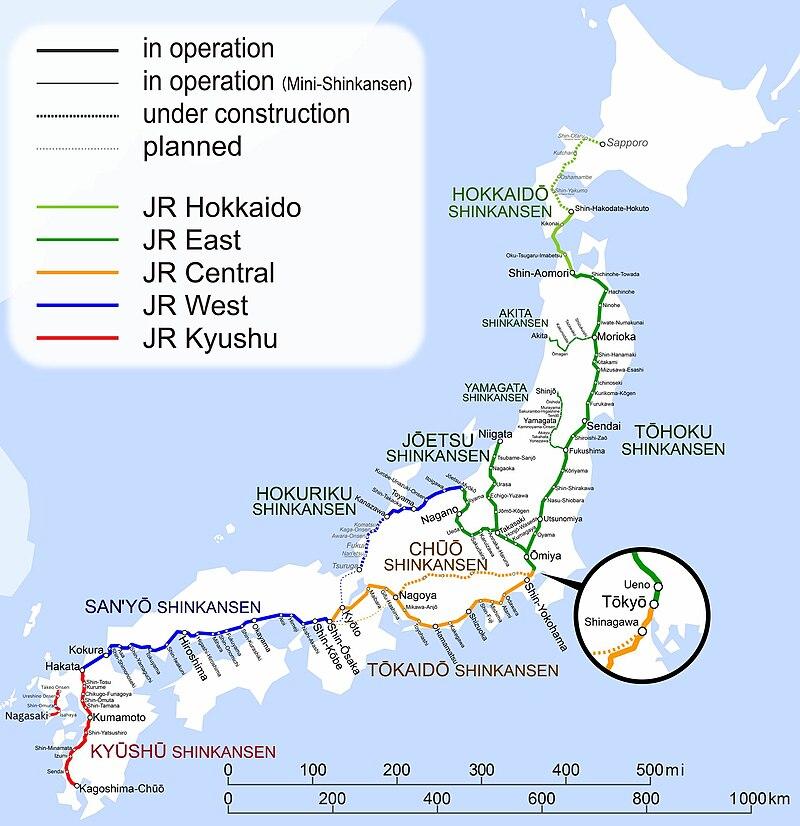

In 1987, Japan privatized the state-owned Japanese National Railways, chopping the business up into seven private companies.

One of these new companies focused on freight, while the other six were entrusted to operate the country’s passenger rail system – each focused on a different geographic region.

This is instructive when it comes to the possibilities (and pitfalls) of creating a profitable passenger rail business.

See, today, two of these firms are still state-owned — Hokkaido and Shikoku.

Like most passenger rail businesses around the world, each has struggled to operate on a self-sufficient basis. That’s left the government unable to drum up private interest in their shares.

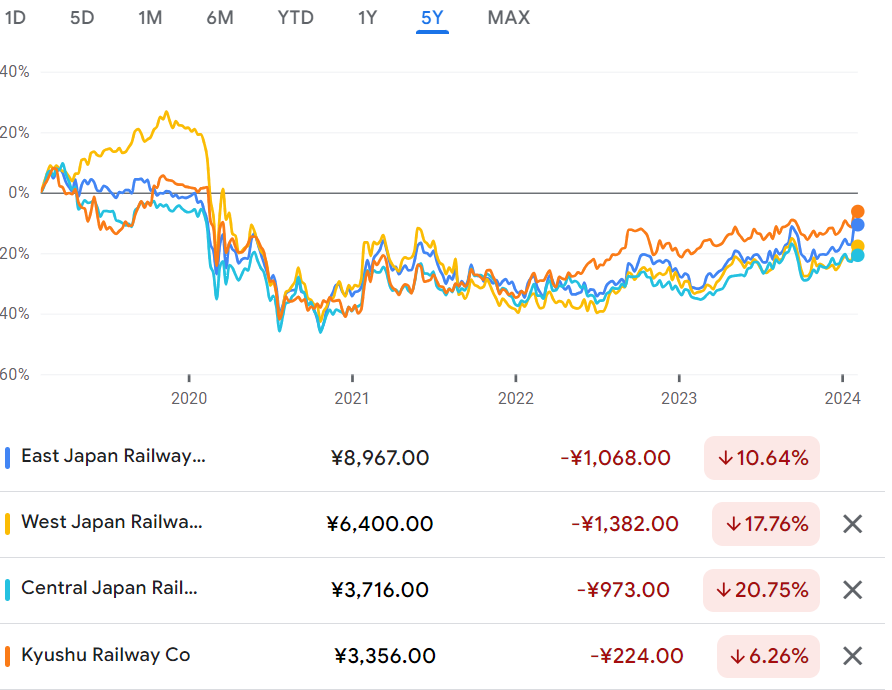

But the remaining four are publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

East, West, and Central are all actually components of the Nikkei 225 index (although Kyushu, as the smallest of the four, isn’t quite there yet.)

So, what can we learn from Japan’s ability to privatize (at least some) of their passenger rail industry?

Lesson 1: Diversify your revenue

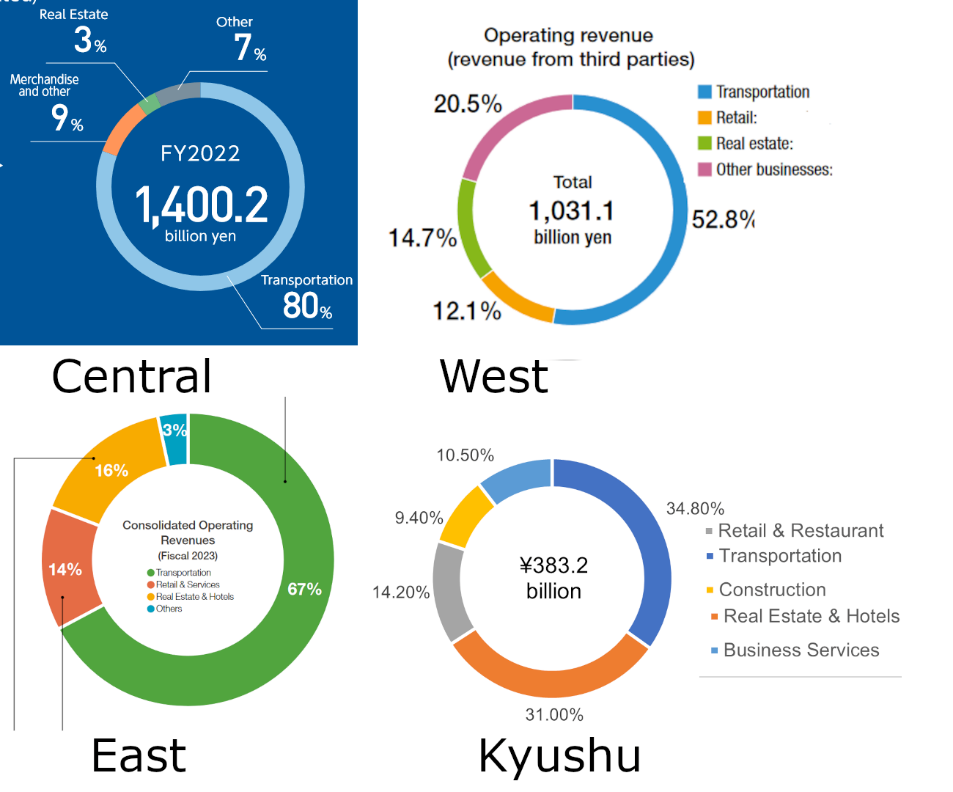

One of the most interesting traits of Japan’s four private rail lines is that they don’t just rely on transportation for revenue.

Both their trains and stations generate revenue in a bunch of related areas.

- They operate restaurants and shops within stations themselves.

- Real estate near major stations is valuable. So they manage hotels and apartments close by.

- Passengers can buy all sorts of upsells and extras.

- Some firms have gotten creative, expanding into construction and business consulting.

To some degree, all of Japan’s profitable private passenger rail firms incorporate this style of revenue diversification.

On the high end, Central gets 80% of its revenue just from transportation. While for Kyushu, transportation accounts for just 35%.

Note: Japan’s model is similar to the airline industry, where it’s hard to turn a profit just on transporting passengers alone. In fact, the value of airline loyalty programs is often higher than the airline itself. (People joke that United is a “credit card company masquerading as an airline.”)

Lesson 2: Fast trains can compete with airplanes

Japan is famous for its bullet trains (known as Shinkansen).

As trains approach speeds of 200mph, the gap between planes and trains starts to narrow.

Empirical evidence shows that the introduction of bullet trains on Japanese lines noticeably decreased the market share of air transport for the same route.

Some countries are even taking this a step further, banning flights that can be done by train. France recently prohibited domestic flights that can be done in under 2.5 hours on a train.

Lesson 3: Some subsidization will probably be necessary

We’ve lauded Japan as a unique example of a profitable modern passenger rail system.

But the truth is, even the successful private firms have some state backing.

While subsidization might not be as explicit as state ownership, the Japanese government is still involved in funding the construction of rail —including paying for the majority of new bullet train lines.

In addition, during the spin-off of these private firms, they basically inherited a fully functioning rail system. That means private investors didn’t have to foot the bill, substantially reducing upfront costs.

Finally, these companies often receive low-cost government construction loans, in addition to some level of regulatory protectionism.

Overall, Japan provides a strong example showing that profitable passenger rail is possible.

But it also might show the inevitability of at least some element of state support.

High-speed rail in America: Brightline and beyond

Brightline’s big Florida experiment

While Brightline has recently captured the public’s attention, the project is a long time in the making.

It all started in…