Today we’re exploring petroleum giant Saudi Aramco; the most profitable company in the world — and yet one of the least understood.

The history of this company is like a back & forth “cold war” between America and Saudi Arabia.

This issue is packed with insights designed to get you up to speed.

You’ll learn:

- What Saudi Aramco is all about

- How California oil companies got screwed out of Iraqi oil rights, and “settled” for Saudi Arabia

- How the Saudis wrestled control from the Americans

- Oil’s incredible economics

- How Aramco uses swing production to control prices 🎟️

- Is America causing Aramco to falter? 🎟️

- Aramco is more than just business: it’s politics 🎟️

- Why Aramco decided to IPO 🎟️

- Saudi Arabia’s future 🎟️

Note: This issue isn’t sponsored by anyone (Can you imagine if Aramco sponsored us?) But to read the full issue you’ll need the All-Access Pass. 🎟️

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

What is Saudi Aramco?

If a friend were describing Saudi Aramco to you for the first time, you’d think they were pulling details straight from a movie script.

The Saudi state-backed oil company:

- Funds the ambitions of a ruling royal family that’s centuries old.

- Sits at the driver’s seat of an international cartel designed to manipulate the global price of oil,

- Operates an intricate web of subsidiaries that stretches 7.5 pages long

- Contributes nearly 70% of the budget revenue for an entire nation,

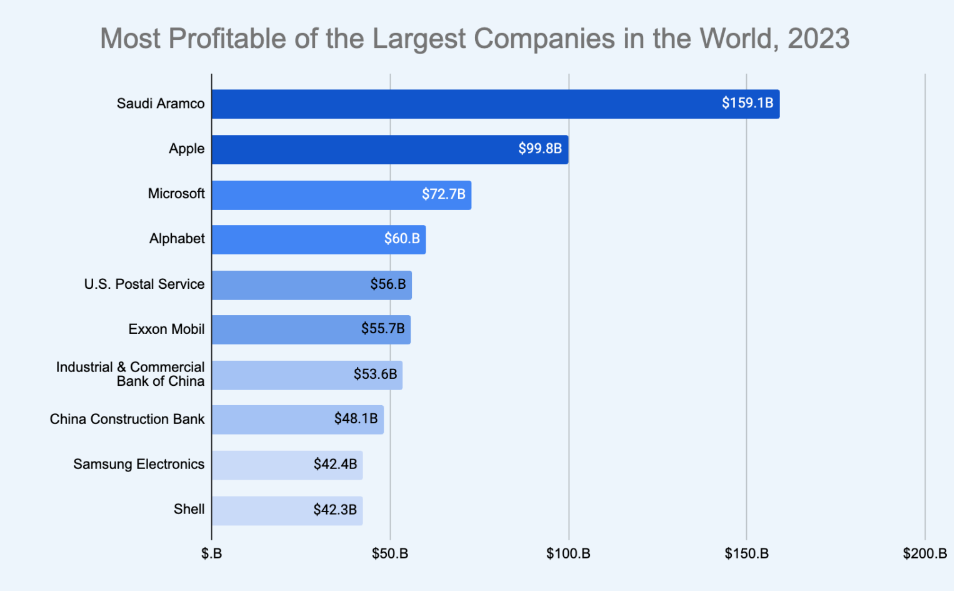

- And is the most profitable company in the world, earning $160 billion in 2022 – the highest annual net income of any company in history.

But despite these fictional-sounding facts, Aramco is plenty real. In fact, the most unbelievable attribute might be the remarkable efficiency Aramco has displayed over the past few decades.

Despite essentially being operated by the whims of a single man, the firm has somehow managed to avoid outrageous political corruption and bloat. This stands in stark contrast to the realities of most state-owned oil companies, especially in places like Venezuela and Iraq.

Aramco is an essential part of the global oil market and near-synonymous with Saudi wealth and power.

But, surprisingly enough, the firm wasn’t even a Saudi project to begin with…

America strikes black gold in Arabia

Like so much of the modern Middle East, Aramco’s story begins with the end of World War I.

As the victorious Entente powers drew new political borders out of the corpse of the Ottoman empire, they negotiated rights to the region’s oil.

Amid significant jostling among British, French, and American interests, a select few companies were given the right to form a “proto-monopoly” over oil in Iraq.

Iraq was largely seen as the most promising location for oil, and the companies left out of the deal had to make do elsewhere. This a group that included the Standard Oil Company of California (also known at the time as Socal, but better known today as Chevron).

Apparently, Socal was one of the few parties that thought that drilling for oil in Arabia had any chance of succeeding — the Saudi king even asked the Californians to let him know if they found any underground water cisterns, so the search might actually provide some value to his people.

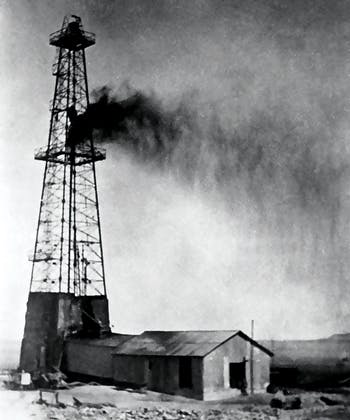

For years, it looked like the naysayers were right, and Socal was wasting its time. Five years went by without a significant find.

But in 1938, the famous Dammam No. 7 well finally struck it big. Within days, the site was producing thousands of barrels of oil.

Socal’s gamble had paid off.

The Saudis wrestle for control

After a brief delay owing to World War II (during which the Italians set a long-distance bombing record trying to destroy the new Arabian oil wells), Socal was ready to get back to business.

By this point, Socal had joined forces with Texaco to develop the wells. But between the two firms, there still wasn’t enough capital on hand to develop the necessary infrastructure.

So they turned to two other companies for a capital infusion — the Standard Oil Company of New York and the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, both now part of ExxonMobil. The four companies renamed the joint entity the Arabian American Oil Company – or Aramco for short.

Entering 1950, Aramco and the Saudi state had a tumultuous relationship. Aramco earned huge profits off the back of the initial deal, all while paying the Saudis a relatively small share of the royalties.

Naturally, the Saudis were unhappy with this arrangement. They used the threat of nationalization and political upheaval to push for fresh negotiations.

Eventually, the Saudis got their way, with an agreement that effectively granted them 50% of Aramco’s profits.

But while this agreement stabilized the relationship for a while, the Saudis weren’t content with just profit participation — they wanted ownership.

In 1972, they finally got it, negotiating the purchase of a 25% stake in Aramco. Over the course of the 1970s, this stake would steadily increase with additional purchases, until the Saudi state became Aramco’s sole owner.

Although a state assuming control of an oil company smells like forced nationalization (looking at you, Iran and Libya) the historical record indicates that this wasn’t the case. Although the full details have never been made public, all parties involved stressed that the Saudi state paid fairly for its shares.

Regardless of the method, the end result was the same.

In 1980, Aramco was fully owned and operated by the Saudi state, and still is today.

Aramco-nomics: Pumping up the profits

Aramco has been an absolute profit-generating machine for the Saudis – in large part because Arabian oil is incredibly cheap to pump out of the ground.

Estimates of Aramco’s cost to produce a single barrel of oil are $5 to $6/barrel (about 10x lower than production costs in the US!)

The market price for a barrel of oil, meanwhile, has fluctuated since the end of Covid from between $60 to $100/barrel

But unlike most firms, Aramco doesn’t have to take the market price for oil as given. As the world’s largest oil-producing firm, Aramco supplies so many barrels that it can actually adjust global oil prices based on its supply decisions – a fact that has seen the firm earn the nickname of oil’s central banker.

Historically, Aramco’s price manipulation abilities have stemmed from Saudi Arabia’s leadership of OPEC.

But as it turns out, that role may be less important than it initially seems.

How Aramco uses swing production to control prices

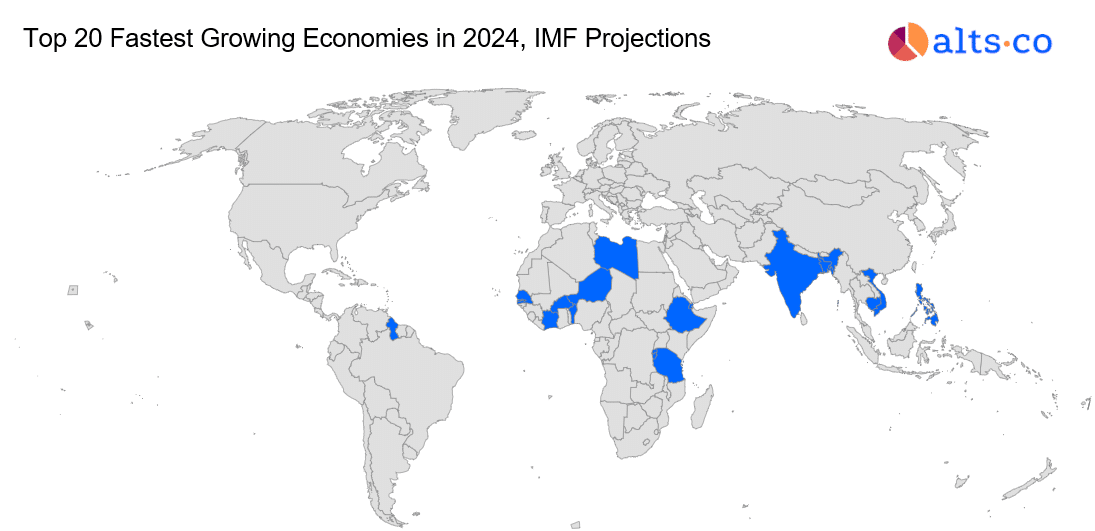

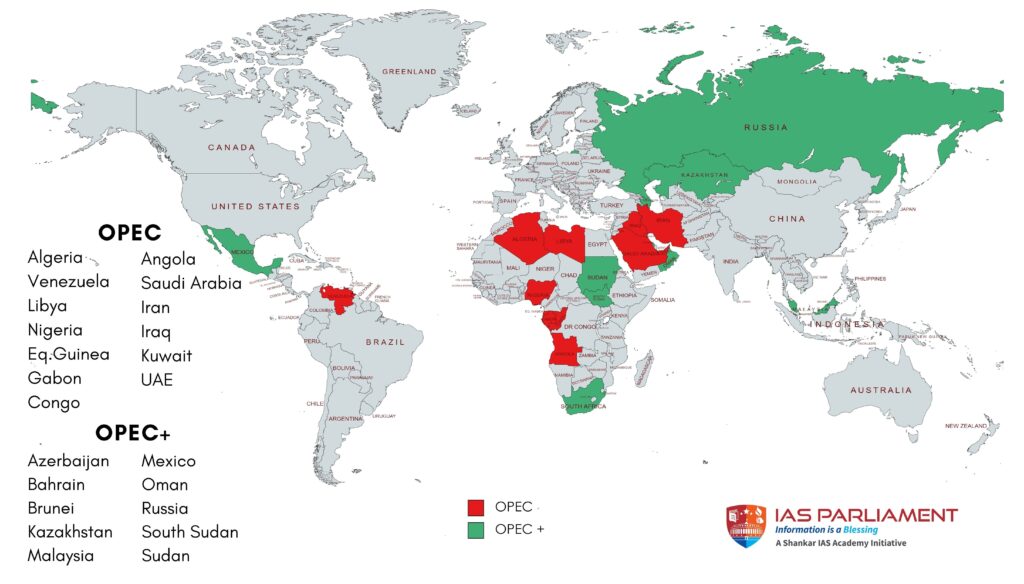

OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) is a group of 13 major oil-producing countries, which between them account for about 30% of global oil production.

In 2016, ten more countries signed up to a looser grouping known as OPEC+, bringing production under purview to about 40%.

Saudi Arabia, as one of the original founding members and the world’s largest oil producer, is OPEC’s de facto leader.

And since Aramco is essentially an extension of the Saudi state, this gives the firm tremendous power over oil prices.

In reality, though, OPEC has much less power than it would seem. Cheating by member states is rampant, since each individual country has a profit incentive to pump more oil than OPEC allows.

Instead, Aramco’s pricing abilities have stemmed from its ability to act as a swing producer.

A swing producer can quickly ramp supply up or down as needed, which can result in significant control over market prices when other producers cannot adjust as quickly.

Due to Saudi Arabia’s historically high spare oil production capacity, Aramco has been well-suited to play this role.

But moving markets as a swing producer still requires a supplier to make up a significant portion of the global market. And this fact about Aramco can no longer be taken for granted.

The rise of American production

While still an important player, Aramco’s domination of the global oil market appears to be faltering.