Plus, we’re investing in a professional rugby team!

Today I’m writing from Queenstown — a small, stunning town on New Zealand’s South Island. 🏔️

I’m here to hike The Remarkables, and meet with the owners of the National Rugby League’s newest team. (More on that in a moment)

Today’s issue is on the economics of stadiums — specifically stadium financing.

Earlier this week, voters in Kansas City rejected a plan to build new stadiums for the Royals and Chiefs. The proposal, which would have raised sales taxes for 40 years, failed by a wide margin.

The practice of providing public funding for private sports teams has always been a bit odd. It’s essentially a transfer of wealth from taxpayers to team owners.

What we want to know:

- Is this transfer worth it?

- What exactly is the economic justification for stadium subsidies?

- How did this all get started?

- Are subsidies actually cost-effective?

- How does this differ around the world?

- Is the future of subsidized stadiums under threat?

Let’s explore 👇

Table of Contents

Want to invest in a National Rugby League team? 🏉

Join as we invest in New Zealand’s newest NRL team.

Pro sports teams are some of the world’s most lucrative alternative investments — and some of the toughest deals to get into.

As far as sports investing goes, rugby is especially compelling. As you may know, it’s already hugely popular in countries like the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.

But here’s the thing: Despite all the love for the sport, there’s only one NRL team in New Zealand, and it’s on the North Island.

So, a special group is bidding to create The National Rugby League’s 18th team. And they’re looking for investors to join them.

- The NRL has stated they will definitely expand to 18 teams. It’s not a matter of if, but when.

- This group is competing against bids from Perth and Papua New Guinea.

- But their bid has a huge advantage: A gorgeous new stadium in Christchurch is already under construction.

As we explore in this issue, they’re “piggybacking” off this publicly financed stadium. Taxpayers agreed to fork out NZ $453m for the build, which will host rugby games, concerts, and hundreds of other events.

We here at Alts are investing in this team. 💪

I met them in Queenstown this week, and realized they are perfectly suited to make this a reality.

It’s a no-brainer for us. Opportunities like this don’t come around often, and this is a grassroots collaboration with motivated sports investors.

Want to learn more? Email [email protected]

I’ll introduce you to Mike, Darren, and the team behind this groundbreaking project. 🤝

We’re also doing an upcoming Q&A with the team for Altea members. Apply here to join.

Swing and a miss in KC

Riding high on the back of back-to-back Super Bowl wins, NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs sought to translate local pride into something more tangible — money.

In partnership with Major League Baseball’s Kansas City Royals, the Chiefs pushed for a new sales tax to pay for the construction of a brand-new stadium.

The tax would raise $2 billion to help the Royals build a new stadium, and the Chiefs renovate their old one.

But despite the Chiefs’ recent success and a thinly veiled threat to leave the city if the proposal failed, voters rejected the measure by a 16-point margin.

This Kansas City story isn’t an anomaly.

Sweetheart stadium deals like this require tax dollars to finance these privately-owned projects.

While plenty of stadium proposals have succeeded in the past, voters around the country are starting to push back:

- Earlier this year, the Virginia state government rejected a deal for a new taxpayer-backed arena for the Washington Wizards and Capitals.

- In 2023, voters in Arizona similarly rejected a multi-billion-dollar subsidized entertainment district that would include a new area for the Arizona Coyotes.

- In Pennsylvania, the planned new 76ers stadium faces an uncertain future, and there is significant controversy about the extent of public funding for the project.

This recent opposition may signal a coming change in the public attitude towards stadium subsidies.

History of stadium subsidies

Before the 1950s, public spending for sports stadiums in America was basically unheard of.

Like most other businesses, construction was simply paid for by private interests.

But in a watershed moment in 1953, the Milwaukee government built County Stadium for $5.9 million (or about $68 million in today’s dollars). This was the first baseball stadium in the country to be built entirely with public money.

While the stadium was originally built with minor league play in mind, it ended up attracting the major league Boston Braves away from their longtime home, and straight into Wisconsin.

Just like that, Milwaukee got a major league franchise. Politicians around the US took notice. It was off to the races to approve their own subsidized stadium projects to lure famous teams.

Over the next 17 years, $450 million of taxpayer-funded support poured into 30 stadium projects around the US.

Some of this money came directly from grants, but a more important source was tax-exempt bonds.

The bond ban backfires

In a tax-exempt bond, local governments raise money from investors and give it to private projects with public benefits. (These low-yield bonds are known as munis)

Non-taxable bonds have a lower interest rate than taxable bonds, which is great for the underlying company behind a project, because their financing costs are reduced.

But this also means that even if a private company is paying principal & interest on the bond, there’s a hidden subsidy.

Eventually, the Federal government got annoyed at all the sweet tax revenue they were missing out on thanks to these bonds (both in stadium projects and beyond).

So in response, Congress passed an important law in 1986, saying a project can only qualify for a tax-exempt bond if less than 10% of the debt repayment comes from private activities.

In other words, the government had to pick up 90% of the tab.

Why would the government do something like this?

Well, the idea behind the bill was that no local government in their right mind would be willing to finance more than 90% of the costs of a private project…right?

Wrong.

Local governments kept using this tool to subsidize stadiums. Taxpayers didn’t seem to mind, and it kept the sports teams happy.

What the law did do is radically reduce the ability of local governments to negotiate with sports teams as to who should repay the bonds!

The law made the situation worse, and the practice continues to this day.

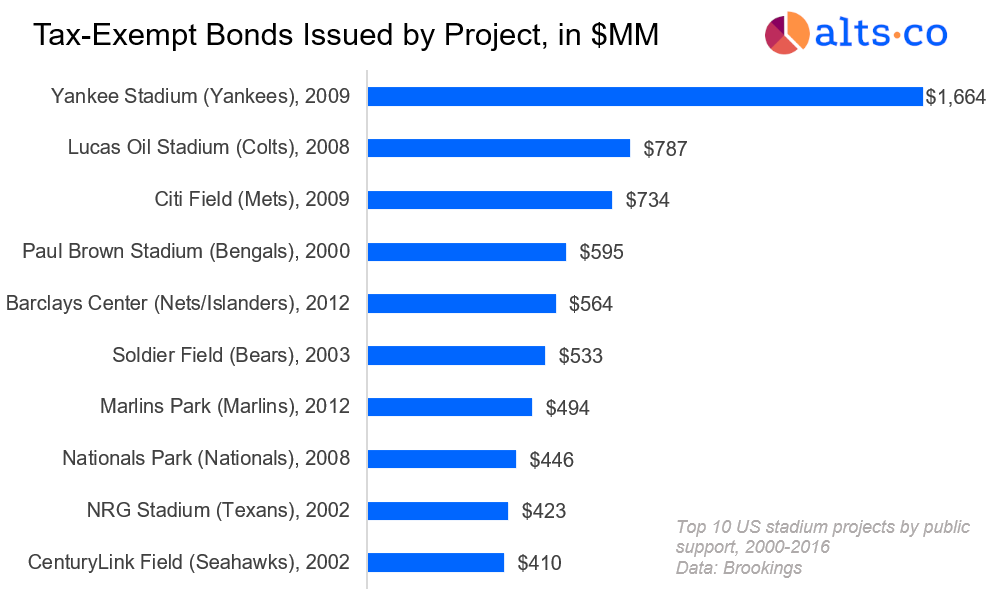

In 2006, New York financed the new Yankee Stadium through a record $1.6 billion in tax-exempt bonds.

And 40% of the Las Vegas Raider’s $2 billion Allegiant Stadium (opened in 2020) was provided from tax-exempt bonds.

Do stadium subsidies work?

Governments don’t just throw this cash around for no reason. They believe it will benefit them in the long run.

Estimates vary on the total amount the public has spent on stadium subsidies, ranging from $4.3 billion to $12 billion since the law passed.

Whatever the precise figure, one thing is clear: this is essentially a transfer of taxpayer money to sports teams and their owners.

Is it all worth it?

It’s tough to say. Proponents argue that stadiums provide more economic benefit to local communities than they cost, and that the optics of transferring money to the rich is just a necessary evil.

Stadium subsidies have benefits..

Increased employment

One major argument in favor of stadium subsidies is job creation.

This was a main justification for New York state’s recent $600 million subsidy for the new Buffalo Bills stadium. Governor Cathy Hochul predicted the creation of “10,000 good paying union jobs” to construct the stadium.

Increased tourism & entertainment spending

Another argument is the promise of greater economic activity due to higher entertainment spending at games. In turn, this higher spending trickles through to the local community.

Sports tourism is another massive (and quickly growing) global industry, so tapping into that market with a new stadium can make sense.

In fact, this was a major argument for public subsidies for Allegiant Stadium, and the local government even introduced a new hotel room tax to help pay for the stadium.

Spending on local shops and businesses

Finally, there’s the idea of stadiums “anchoring” a neighborhood, drawing in customers who then spend money in the local area.

The logic here is that it’s worth a government treating a stadium as a “loss leader,” if it means more job creation and economic activity at other businesses nearby.

..but evidence for these benefits is a bit weak

All these economic benefits sound great in theory, and it’s certainly plausible that they could outweigh the cost of subsidies. But how does it play out in practice?

Given that public stadium subsidies have been in widespread use for 70+ years, we’ve collected solid evidence for whether or not they actually pay off.

The answer is…