Today we have a timely and important issue on investor accreditation.

We’ll discuss:

- The purpose of accreditation

- Why the SEC uses money as the delineator

- Why accreditation rules are severely flawed

- The world’s first accredited investor certification

- Altea: Our new community for alternative deal flow

Note: This issue is free for everyone. Enjoy!

Table of Contents

The world’s first Accredited Investor Certification

In this issue, we discuss the SEC’s rules for accredited investors.

While their new rules take a step towards education, there is still no single definition of financial sophistication.

This is why our friends at Doriot Venture Labs developed QAI: A rigorous exam and simulation that puts your investing knowledge to the test.

What is QAI?

QAI is designed to test and accelerate your knowledge of venture funding principles. Candidates who get a passing score earn the coveted QAI certification.

VCs, angels, and founders who have taken it can attest to two things:

- It’s one of the hardest tests they’ve ever taken

- They understand way more than they used to (36% more on average)

This program isn’t easy. But it’s not meant to be. See for yourself.

Alts readers get $100 off the next cohort (starts Feb 15), and save $50 on the self-study option

America’s unfair investing rules

Here’s a fun fact about American financial regulation: It’s effectively illegal for poor people to put their money into the best investment opportunities.

Now, there’s no specific law on the books saying that only rich people can access good investments.

But explicit or not, there are three reasons why America (and most of the world) essentially has a two-tiered investing system.

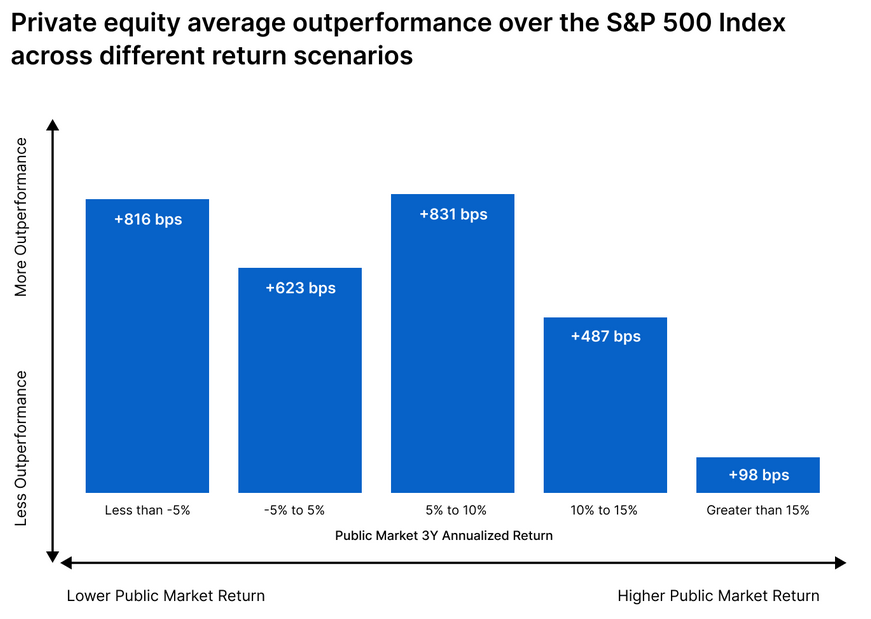

Private markets outperform public markets

This isn’t a hard and fast rule, there are exceptions galore.

But consider the following:

- Startups are taking longer to go public, meaning the fastest-growing companies are still private (like OpenAI or SpaceX).

- Information is more fractured and murky in private markets. This creates a situation where active managers can exploit price inefficiencies and generate alpha.

- Private investments are harder to trade, which increases returns through an illiquidity premium.

Now, one argument is that the perception of private market outperformance is because asset values are simply updated less frequently, which gives the illusion of higher returns.

Another is that survivorship bias is more severe in hedge fund and startup data, meaning failed investments are often not included in calculations.

But on the whole, the argument that private investments truly do outperform public ones appears convincing.

You must be ‘accredited’ to buy most private investments

If you’re raising money in the US, you generally need to register the offering as a security with the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission).

Registration is expensive and comes with a slew of onerous requirements, including regular publication of audited financial statements, and disclosure of information that companies may not want to share with the world.

Obviously, companies would prefer not to register if they don’t have to. So the SEC offers ten exceptions to avoid many of the requirements (including Regulation D Rule 506, which our ALTS 1 Fund falls under).

There are lots of rules we’ll skip over. But what it boils down to is that most private investments are only available to accredited investors.

But what makes someone accredited, anyway?

Accreditation is (unfortunately) all about money

In the eyes of the SEC, “accredited” is just a euphemism for sophisticated, or trusted. The idea is that accredited investors are trusted enough to fend for themselves,

In other words, since accredited investors don’t need the SEC’s protection, their investments don’t need to be held to the same standards. So the SEC lets them invest in opportunities regular investors can’t.

Now, there’s no doubt that private investing is riskier than public investing – which is why education is vital. After all, without training (like what our friends at QAI have created), it’s hard to differentiate legitimate investment opportunities from garbage and outright fraud.

But here’s the thing: To test whether an investor is able to look out for themselves, the SEC doesn’t really rely on knowledge or expertise. Instead, it’s mostly about money.

In the US, to qualify as an accredited investor based on financial criteria, you need either:

- Net worth over $1 million, excluding your primary residence*, or

- Income over $200k/year (or $300/year with a spouse) for the past two years.

*Note: This rule is especially bizarre. I’ll explain why below.

Introducing Altea 🌱

Our new private community for accredited investors.

Private markets have evolved over the years, and so have communities.

But one thing has remained constant: You need connections to invest in the best deals, many of which have $50k+ minimums.

Altea is a supportive community we’ve created for accredited investors.

It gives you access to better alternative investment deals, a robust network of compelling individuals, and once-in-a-lifetime travel experiences.

We are looking for founding members to join our first cohort.

You’ll get:

- Top-notch alternative deal flow

- A community of 10x givers. Folks who love being helpful and making connections.

- Unlimited access to Deal Desk, our database of live deals

- Expert speakers from our favorite alternative asset classes

- Exclusive travel experiences (like our upcoming trip to Mexico)

We’re looking for people to help build and nurture the community. Contribute to discussions, join events, chime in with due diligence, and invite other exceptional folks to join us.

And if you’re accredited, apply as a Founding Member

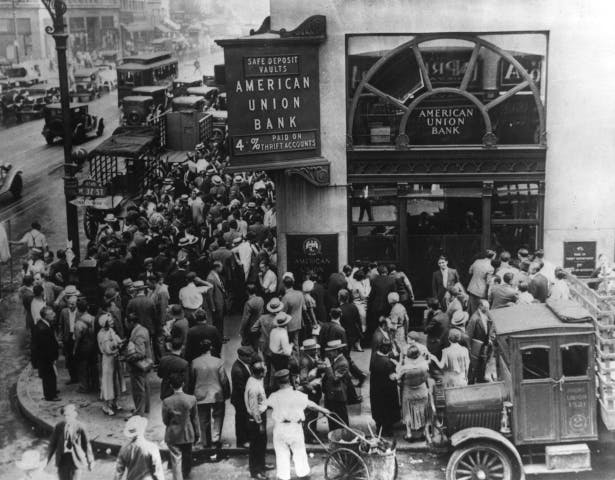

Why do accreditation rules exist?

Well, let’s just say it’s rooted in good intentions.

Part of the SEC’s mission is to “protect investors.”

Traditionally, it has done this by ensuring people have access to truthful, comprehensive information to make their own investment decisions — an approach known as the disclosure philosophy.

But lately the SEC has occasionally strayed from this philosophy, and some recent decisions seem to have nothing to do with disclosure.

The SEC’s new philosophy of risk

The SEC has started to police not just disclosure, but also risk.

Usually, it’s up to investors to decide the risks they want to take after considering all the information.

But in a few cases, the SEC has decided what risks investors can take!

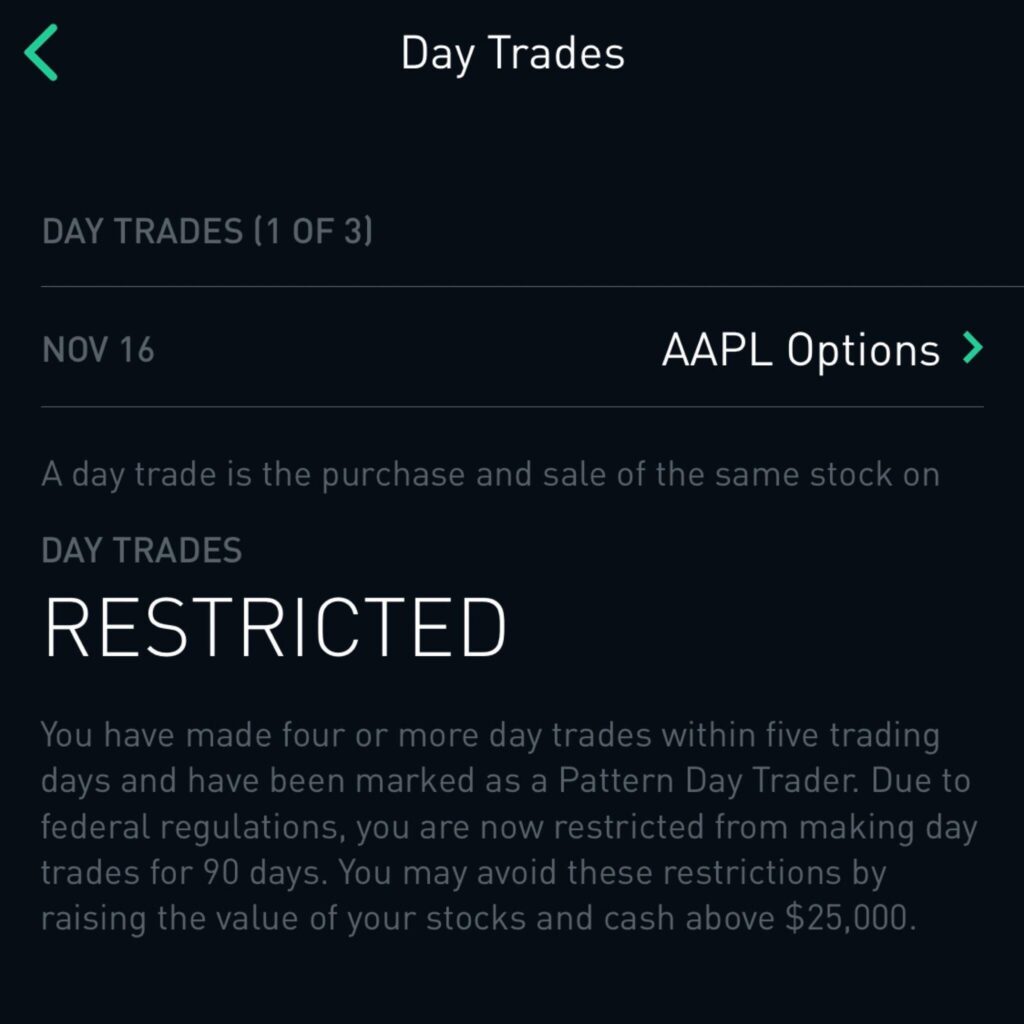

- The SEC has not approved any ETFs with over 3x leverage. They almost did in 2017, but eventually walked back their approval.

- After scores of day traders went bankrupt during the dotcom bubble, the SEC created Pattern Day Trading rules, which banned small accounts from making too many daily trades.

- The SEC declined to approve a spot Bitcoin ETF, despite acknowledging that Bitcoin isn’t even a security.

Ultimately, a court forced the SEC to approve the Bitcoin ETF, stating that the agency was being ”arbitrary and capricious” in its refusal. Last week, those ETFs finally went live.

It’s hard to rationalize these decisions based on disclosure.

Instead, it seems like the SEC is trying to “protect” investors from losing money by limiting access to investments or strategies it deems too risky – an approach we can call the risk philosophy.

Officially, the SEC has stated that the term accredited investor is:

…Intended to encompass those persons whose financial sophistication and ability to sustain the risk of loss of investment or ability to fend for themselves render the protections of the Securities Act’s registration process unnecessary.

So, according to the SEC, accredited investors don’t need protection because:

- Their level of financial sophistication is high enough to not need traditional disclosure requirements (disclosure philosophy)

- They can sustain the potential financial loss associated with not having traditional disclosure requirements (risk philosophy).

The accredited investor rules exist at the intersection of both approaches. And this right here is why the SEC uses money as the delineator.

Are people with a higher net worth or income more financially sophisticated, and better able to handle losses in private markets?

Probably.

But this reasoning is still incredibly weak when you consider the inconsistencies and hypocrisy in the current system.

Accredited investor rules don’t make sense

To illustrate why, let me tell you a quick story about how I became an accredited investor.

In 2013 my wife and I bought our first house — a modest starter home in California. We lived in this house for six years, during which time the value of California residential real estate appreciated significantly.

In 2019, we moved to Australia and rented an apartment in Melbourne, meaning our California starter home was no longer our primary residence.

Boom. Suddenly, just like that, in the eyes of the SEC, I was now an accredited investor — a person capable of making wise decisions and investing in the lucrative world of private markets. Hooray!

This is just one absurd example of (unintentionally) gaming the system to reach accreditation status. Any startup founder who raises millions or gets a 409A valuation immediately becomes accredited too.

Keep in mind that startup founders are some of the least risk-averse people in the world. Despite risking their careers, relationships, and investors’ capital, the SEC says they are well-suited for accreditation.

The arbitrariness of this whole thing boggles the mind.

But the larger point is this: As a matter of policy, I would argue the SEC shouldn’t have a risk philosophy to begin with.

Why? Because there’s no way for the SEC to consistently determine what constitutes acceptable risk!

Think about it:

- The SEC doesn’t take the size of the investment into consideration at all. Can someone with a $2m net worth sustain the loss if they invest 90% of their money into a single bad investment?

- Why are non-accredited investors allowed to buy stock options (which contain massive leverage) but not invest in their friend’s startup?

- Why are non-accredited investors allowed to invest in cryptocurrencies, but not invest in hedge funds or private equity?

- Determining the risks investors can take feels outdated in a world where sports betting apps have over 16 million monthly users.

The fact is that money is a poor measure of an investor’s need for disclosure protection.

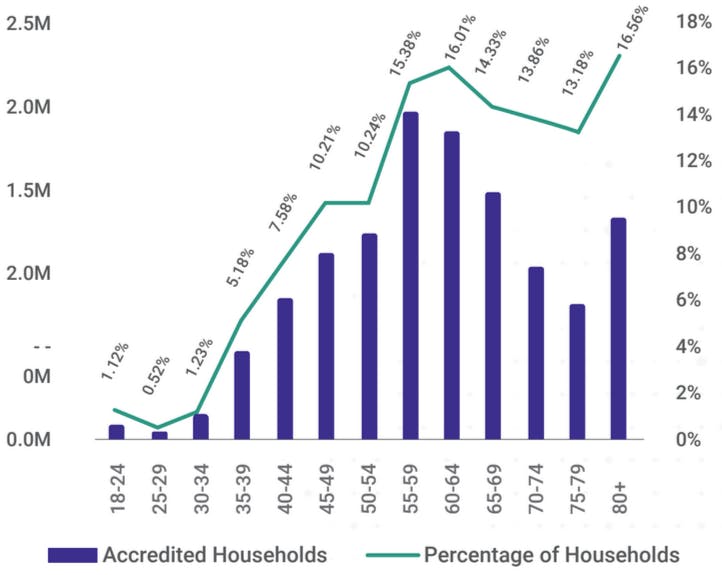

There’s just no reason to think that a dentist making $500k a year is automatically more qualified to make investment decisions than an accountant making $100k.

Plus, wealth compounds throughout life, so plenty of people nearing retirement gradually eclipse the investor accreditation requirements without any necessary increase in their financial sophistication.

So, if the SEC’s risk philosophy is illogical and inconsistent, it’s just left with the disclosure aspect.

I would argue the need for disclosure depends on each investor’s financial sophistication, and that this sophistication should be based on not money, but education and training.

How should investor sophistication be determined?

A better approach to accreditation is a widely available financial sophistication test.

Private investing is like driving a car:

- It’s useful if you know what you’re doing

- It’s very dangerous if you haven’t practiced before you get behind the wheel

- Pretty much everyone can learn how to do it

Beyond fraud and misrepresentation, non-investable companies are rampant in the private markets, which is why being financially sophisticated is so important. Being able to leave one’s own biases at the door and objectively analyze investment opportunities are key in private ventures.

The SEC has the authority to approve a general accreditation test today, but they’ve shown some hesitancy to do so.

One bill passed by the US House of Representatives (H.R. 2797), would require the SEC to do this. But the bill is still some way from being enacted.

By law, the SEC needs to review its accredited investor definition every four years, and the agency is currently in the process of doing so. So the time could be ripe for a change.

One possibility is that the SEC could authorize certain investment certifications to verify accreditation status — including the Qualified Accredited Investor certificate from a company called Doriot (today’s sponsor).

The SEC is currently in the process of reviewing Doriot’s application.

This might be particularly true given the SEC is signaling that the accreditation wealth thresholds could increase to account for inflation.

Since doing so would make the system even more exclusionary, it could create greater pressure for the SEC to implement a general accreditation test.

Now, if you’re itching to make private investments today, there are a few workarounds to the existing accreditation system — some of which are SEC-approved.

How to get around accreditation restrictions

Perhaps in recognition that accredited investor rules unfairly limit access to certain investments, the SEC has shown an increased willingness to facilitate workarounds.

In 2020, for instance, the SEC modernized the accredited investor definition by expanding accreditation to people with certain professional certifications.

Specifically, if you can pass the Series 65, Series 7, or Series 82 financial regulatory tests, you might be able to become an accredited investor without needing to meet the financial requirements – but the process isn’t exactly simple:

To qualify as an accredited investor under these tests, you need to hold these licenses “in good standing.”

For the Series 65, for instance, that means you’d need to be registered as an investment adviser representative – essentially meaning you work for an investment advisory firm.

- Not only that, but both the Series 7 and Series 82 tests require sponsorship by an existing financial firm, so you can’t even take them without having the right job in the financial industry (the 65, though, has no sponsorship requirement).

- Finally, these are financial regulatory tests – meaning you’re going to be spending a lot of wasted time memorizing stuff that has nothing to do with evaluating private investment opportunities (like under what circumstances an adviser can receive gifts from clients).

This update might be good news for people in the financial industry, but it’s still far from a general “accreditation test.”

Another possible workaround is to only invest in private opportunities that are open to non-accredited investors – which do exist, albeit in a limited state.

Private opportunities for non-accredited investors

Under Reg D, we saw how the SEC allows you to do an unlimited private capital raise if you sell to accredited investors.

The SEC does allow some private capital raises for non-accredited investors, with varying degrees of restrictiveness:

Rule 504

This is a specific exemption within Reg D that allows companies to raise up to $10 million in a 12-month period from any type of investor without registration.

But unlike other forms of Reg D offerings, Rule 504 does not allow companies to solicit the general public or ignore state-level securities laws, which vary greatly. That can add a huge amount of complexity to the process.

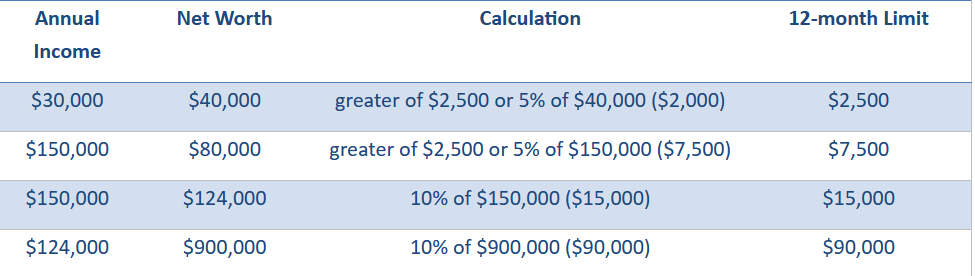

Regulation CF

This exemption allows companies to raise up to $5 million through an online crowdfunding platform without registration – but non-accredited investors are limited in the amount they can invest.

Regulation A

This is the heavy hitter in the world of non-accredited private investing.

“Reg A” got off the ground in 2015 and has a couple options:

- Tier 1 offerings can raise up to $20 million from any type of investor with few requirements.

- Tier 2 offerings, meanwhile, can raise up to $75 million — but, similar to Reg CF, there are investment restrictions for non-accredited investors. Plus, this tier requires a company to have audited financials and file regular reports with the SEC — not quite full registration, but not Reg D freedom either.

It also might be possible for non-accredited investors to participate in intrastate capital raises, which are governed by a state’s Blue Sky laws rather than the SEC.

It’s important to note that none of these workarounds diminish the importance of education before getting involved in private markets. Bypassing accreditation opens up the possibility of private investing, but it doesn’t necessarily make it a good idea.

All of these accreditation workarounds are SEC-approved.

But there’s one that isn’t so squeaky clean.

Another big secret about accreditation

Many private investment offerings are off-limits to non-accredited investors.

But how do those offerings determine if you’re accredited anyway?

Ultimately, it depends on the specific offering – but funds raising money through one of the most popular registration exemptions Reg D Rule 506(b) usually allow investors to self-verify their accreditation status.

Self-verification isn’t enough for some offerings, including Reg D Rule 506(c) exemptions.

But in certain cases, you may just be able to basically “check a box” that says you’re accredited and, well, nobody will really check…

(Note: Popular platforms such as AngelList, Republic, and StartEngine all require a letter from an accountant stating you meet the definition of an accredited investor).

NOTE: I am absolutely not recommending you do this!

I am merely pointing out that there is a ton of regulatory structure in place for something that isn’t even always enforced — and whose value, in my opinion, is increasingly dubious to begin with.

But in the meantime, we need to live with the rules we have.

If you want to level up your financial knowledge and take a step towards accreditation, consider QAI’s exam.

And if you’re accredited and looking for a trusted, vetted community to share the world’s best alternative investment deals, apply to become a founding member of Altea.

What do you think?

Accreditation is a fascinating, contentious topic. Let us know your thoughts. We read everything.

See you next time, Stefan