Today, we’re continuing our Ethics & Assets series with a look at museums.

We often refer to blue-chip alternative assets as being “museum-worthy.” But while that phrase rolls nicely off the tongue, the reality is much more complex.

There are often huge issues surrounding who should own a museum’s assets, and why. Although the act of displaying cultural relics for public enjoyment is unquestionably a good thing, it raises some important questions:

- Is it right for museums to own stolen artifacts?

- Should museums have to pay for these artifacts?

- Does public education and enlightenment outweigh the challenges that original owners face?

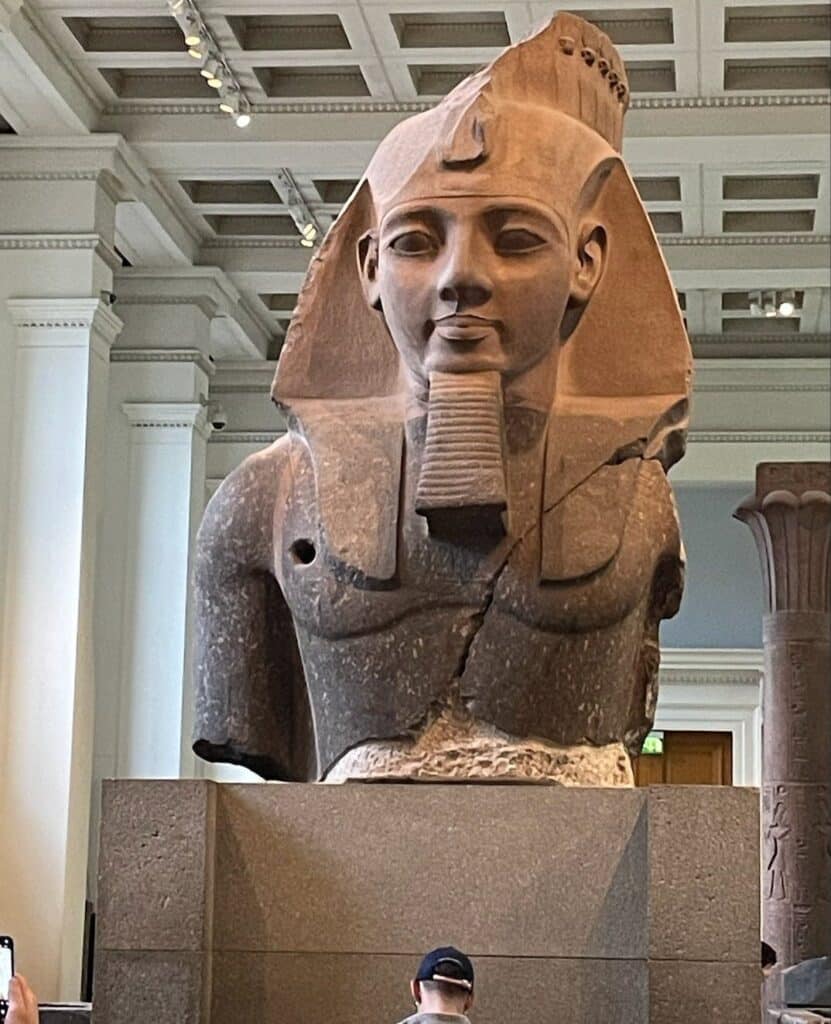

This is a topic I’ve wanted to write about for ages, and a recent trip to the famous British Museum in London inspired me to do so.

If you enjoy this, check out our other issues in our Ethics and Assets series: The Story of the Aboriginal Flag, and Investing in People.

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

Museums over time

It’s funny — we tend to think of museums as a modern phenomenon. We look at ancient, primitive cultures and marvel at how different our lives are now.

But every generation thinks they’re living during peak humanity, and looks to the past for inspiration. The Titanic‘s Grand Staircase was adorned with ancient Roman military symbology. Rome itself is chock-full of Egyptian relics. And on and on we go.

And while it certainly feels like the world is moving faster than ever (and technically, it actually is), pausing to admire the past is nothing new.

The world’s oldest museums date back 2,500 years. But these were private collections of wealthy families. Can you really call them museums?

Capitoline Museum in Rome is considered the world’s oldest public museum. It dates back to 1471, when Pope Sixtus IV donated a bunch of bronze sculptures to the city. 263 years later it opened to the public.

Today, there are around 55,000 museums worldwide, with an astounding 15 of the top 20 most popular all located in just four cities: Paris, Washington DC, London, and New York.

But the museum I’d like to focus on today — and the one at the center of so much museum controversy — is the mighty British Museum.

The British Museum 🇬🇧

Last month, I had the pleasure of finally visiting this museum, and…my God. I was blown away. Total cultural overload.

It’s arguably the single best museum in the world. And with 8 million pieces, it’s certainly the largest. (Interestingly though, only around 1% of the collection is on display to the public. The rest is stored in warehouses around Britain)

The museum holds incredible artifacts from all over:

- Lavish, jewel-encrusted crowns owned by the Rothschilds and Hapsburgs — including a single thorn from the crown of thorns worn by Jesus when he was crucified.

- Roman mosaics, which casually line the floors and stairwells.

- Enormous Egyptian mummies and hieroglyphs. (The museum has the largest collection of Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt.)

- A stone-chopping tool that doesn’t look like much, but is 2 million years old.

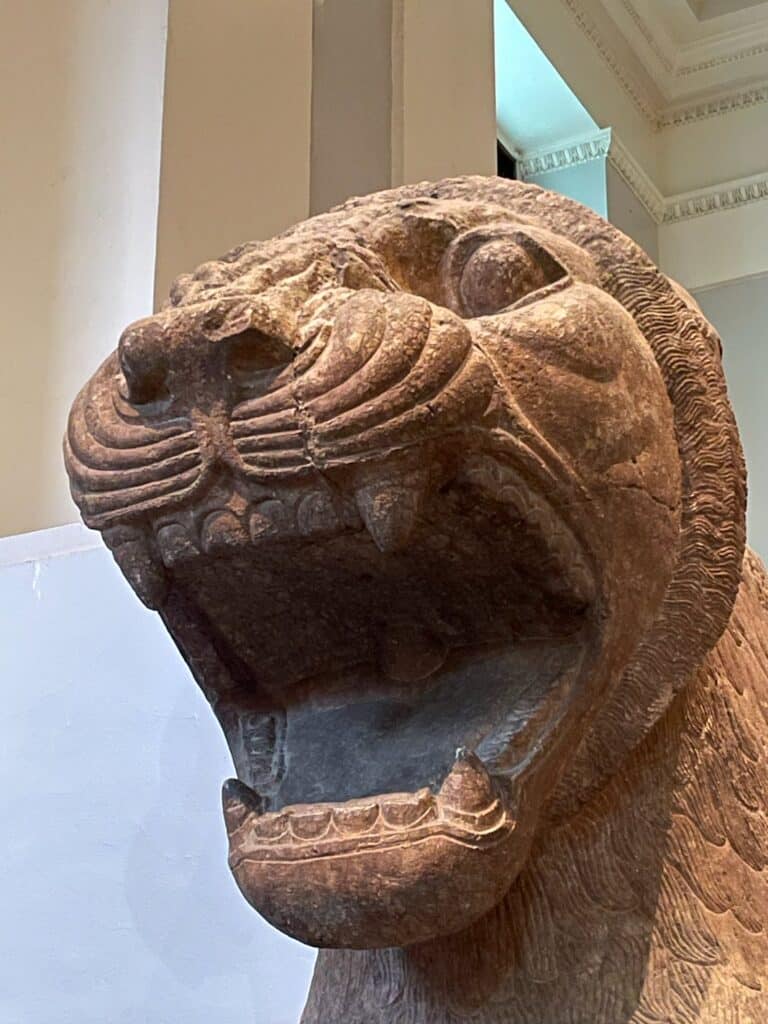

- Marble lions from the Tomb of Mausolus, one of the seven ancient wonders of the world.

- And another 15-ton guardian lion from the Assyrian Temple of Ishtar

Culturally significant items from hundreds of countries line the hallways; a visible legacy of a brutal colonial past. Most of the 6 million visitors per year probably don’t think much of it. But to a growing number, this showcase feels like “trophies in a collection.” The British Museum is far from alone in this, of course. But it’s the most well-known collection in Britain, and arguably the world.

Moai Statue 🗿

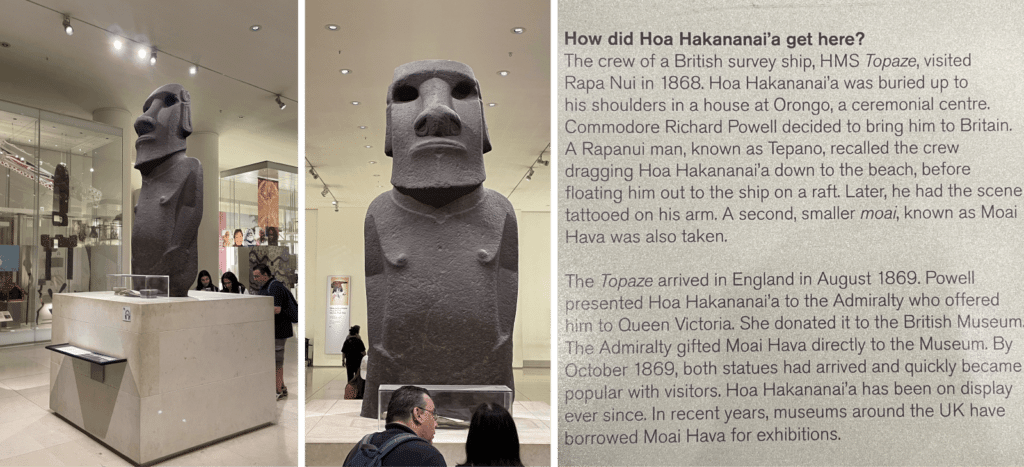

One of the most controversial artifacts at the museum is the massive Moai Statue from Easter Island.

Hoa Hakananai’a (translated as ‘lost or stolen friend’) was taken from the island by the British in 1868. The Governor of the Easter Islands has pleaded with the British Museum to return the piece.

It could be ignorance or naivety on my part, but I had no idea the museum had one of these, and I was floored when I first saw the imposing, 4-ton piece of carved lava rock.

The Rosetta Stone 🪨

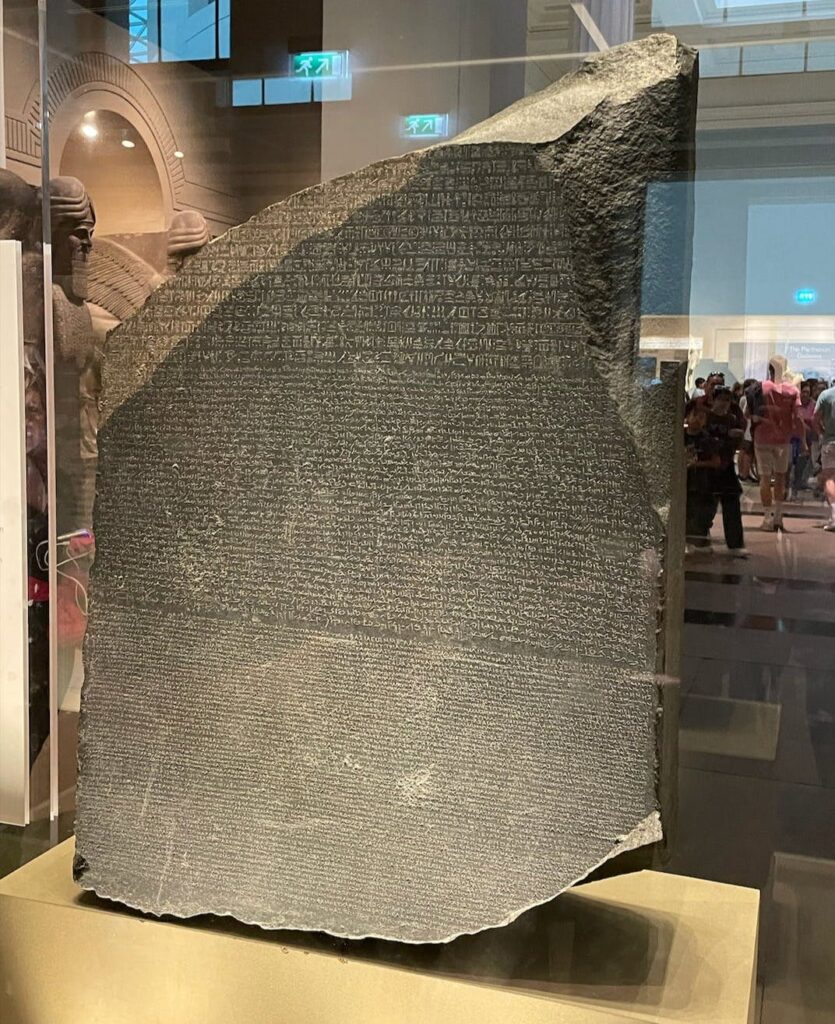

Another hugely controversial item at the museum is the Rosetta Stone — one of the world’s most important artifacts.

The stone, which taught humans to read hieroglyphics, was uncovered by accident by Napoleon’s army in Egypt in 1799.

The French immediately recognized its significance, and claimed it as their own. But two years later, the British stormed Egypt and defeated the French.

As part of the surrender terms, the French were forced to relinquish dozens of Egyptian antiquities to the British. The most famous of these was the Rosetta Stone.

So what’s the problem?

The problem is that it wasn’t really theirs to give.

Recently, Egyptian residents and the government have protested Britain’s ownership of the sacred rock. There are two major petitions with over 100,000 signatures. Both petitions argue that Egypt had no say in the 1801 agreement.

In their reply, the British Museum said the 1801 treaty included the signature of an Ottoman admiral who fought alongside the British. They argue that since an Ottoman sultan ruled Egypt during Napoleon’s invasion, the admiral represented Egypt.

It’s their roundabout way of saying, “tough shit.”

The Parthenon Sculptures 🏛

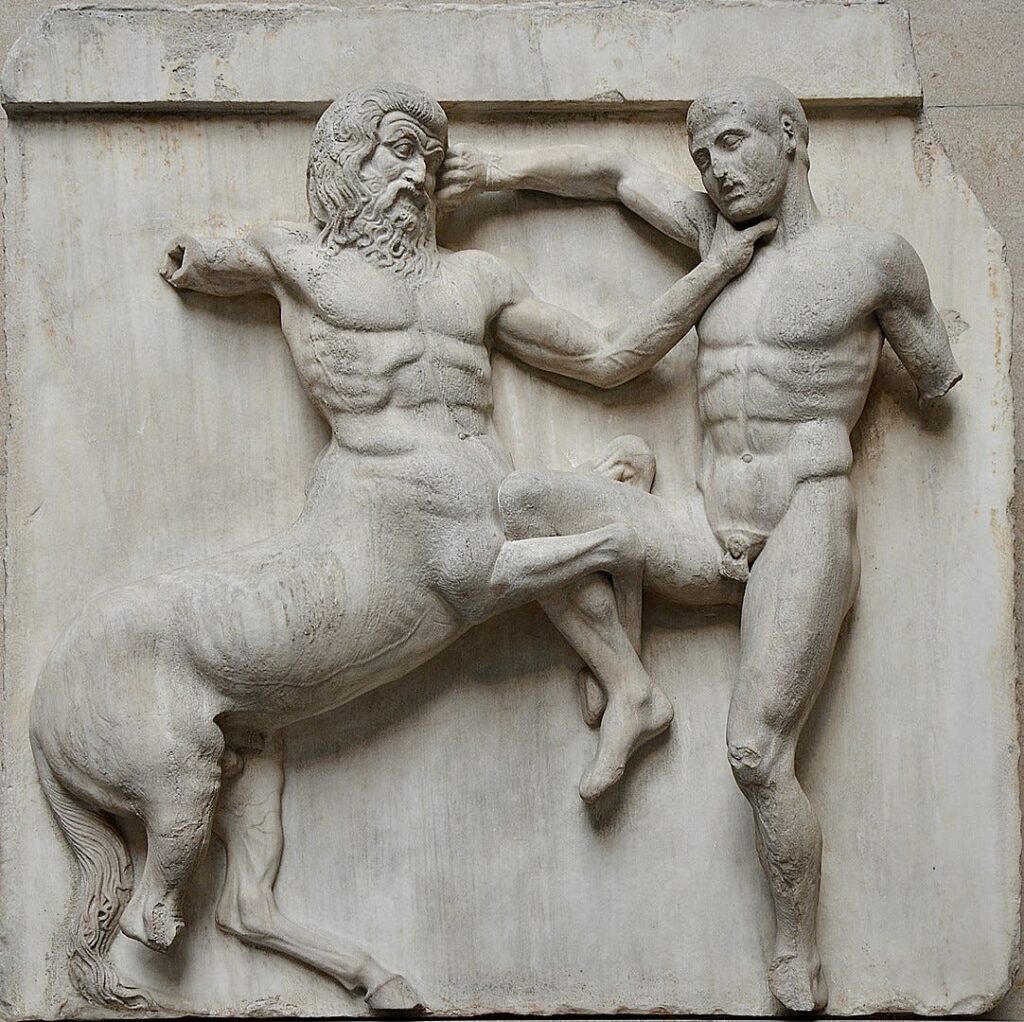

The Parthenon Marbles (also known as the Elgin Marbles) are yet another extremely controversial exhibit.

The stunning, intricate sculptures were originally part of the Parthenon — the famous 2,500-year-old temple dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena.

Carved by Ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, these pieces were torn from the Parthenon in the early 1800s during the expansion of the British Empire, and brought to Britain by Lord Elgin in 1801. (The same year as the Rosetta Stone. What a banner year of plundering for the Brits!)

For 220 years, the ownership of these has been contested, and now the Greek government is ramping up the pressure to get these back.

To its credit, the British Museum has been a fantastic steward of these ancient relics, and of course has some very uhh, interesting statements explaining why they won’t be returned.

But the drumbeat is getting very, very loud on this.

George Clooney, who directed and starred in The Monuments Men (a film about returning art masterpieces from Nazi thieves) has spouted off on this topic:

There are a lot of historical artifacts that should be returned to their original owners. But none is more important than the Parthenon Marbles. – George Clooney

His wife Amal Clooney, the famous human rights laywer, once advised the Greek government on how best to reclaim the marbles.

But remember that no international legal framework exists for these disputes.

Unless there is evidence that an artifact was acquired outside what are considered “acceptable channels,” repatriation is left largely to the museum’s discretion.

So far, The British Museum hasn’t budged.

Other contested museum holdings

Priam’s Treasure (aka “The Trojan Treasure”)

Most people know about Troy thanks to Brad Pitt.

But the mythical city was real, and in the 1800s, the treasure trove of the last king of Troy, “King Priam,” was uncovered by German archaeologists. It was held in a German museum until 1945 when, during the fall of Berlin, Russians looted the museum.

The Russians stated this looting was legal as restitution for the bombing of Russian cities. It is now held in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Germany has not pursued this since.

Also of note — the excavations performed by the German archeologists irreparably destroyed the site that may have held more 4,500-year-old treasures of Troy. (Nice going, guys 👍)

Man-eating lions of Kenya

The Tsavo lions were a pair of lions in Kenya’s Tsavo region that gained notoriety in the late 1800s for eating British workers during the construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway.

In total the lions ate over 200 men (!) Colonel John Henry Patterson, the guy overseeing the railway project, eventually killed both lions. In 1899 their bodies were taxidermied and sold to Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, where they’ve been kept ever since.

But these lions hold cultural importance in Kenya, and Kenyan authorities have expressed a desire to repatriate these iconic animals.

This insane story was turned into a best-selling book called The Ghost and the Darkness.

A selection of music as big as the British Museum 🎵

Have you ever considered owning a song and getting a share of the royalties?

JKBX is a new platform where you can invest in music just like stocks, through what they call Royalty Shares.

Yes, other music marketplaces do something similar. But the songs available are never that great.

JKBX, on the other hand, has an incredible selection, including:

- “Halo” as recorded by Beyoncé

- “Welcome to New York” as recorded by Taylor Swift

- “Lean on” as recorded by Major Lazer

- “Sucker” as recorded by Jonas Brothers

- “Rumour Has It” as recorded by Adele

This company hits all the right notes. It’s a potential game-changer, and they’re launching soon.

You don’t want to miss this. Check out JKBX now.

A new trend: Artifacts are returning home

If the topic of stolen goods seems a bit doom & gloom, there’s plenty of room for hope.

In fact, the recent trend is that artifacts are returning to their places of origin.

The Met returns an Egyptian coffin

In 2019, New York’s Metropolitan Museum returned 16 antiquities to Egypt after an investigation in the US concluded they had been illegally trafficked. The Met also apologized to Egypt.

Benin Bronzes return to Africa

In 2021 and 2022, Nigeria and Benin scored major repatriation victories with the Benin Bronzes; A series of ornate metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin.

London’s Horniman Museum has also returned its collection of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. They were stolen in the late 1800s by British Colonial troops. The artifacts ended up in museums in Europe and the US, and African leaders have been working to get them back for decades.

France also returned 26 Benin treasures they had pilfered 129 years ago, marking the most significant restitution of artifacts under French President Emmanuel Macron.

Macron’s pledge to return stolen African artifacts has brought this issue back in the public eye, and nudged Germany to do the same.

But it hasn’t had any effect at the British Museum…

US returns antiquities to Turkiye

Just this past April, the United States returned $33 million worth of artifacts back to Turkiye.

The 12 relics were smuggled out of the country over 50 years ago, and include a headless bronze statue, possibly of Roman emperor Septimius Severus, dating back to 225 CE.

Over the past twenty years, 1,203 cultural goods have been returned to Turkiye, underscoring the country’s efforts to combat cultural property smuggling and safeguard the history of this incredibly important part of the world.

Closing thoughts

I love museums. They play an important role in preserving history, and are the only places where it’s possible to see the world under one roof.

Some may call it the world’s largest receiver of stolen goods, but the British Museum completely blew me away.

It wasn’t just the collection; it was the quality, the organization, the attention to detail. Oh, and did I mention it’s free? I have a healthy respect for how much work goes into this stuff. They do a spectacular job.

That said, colonizers (especially the British) have a history of err, “picking up” anything they thought was valuable. And countries ravaged by colonization have begun to understand the significance of the heritage they’ve lost. They’re now (reasonably) asking for it to be returned to its geographical homeland.

However, despite pressure in recent years to return works, very few museums have actually done so. Why? Because a) museums like money, and b) the repatriation issue isn’t black & white.

Museum proponents argue that antiquities — regardless of whether they were stolen — should remain there simply because they’re far better equipped to study, conserve, and display these delicate artifacts. They argue this stuff is better off housed inside a secure institution with 24/7 security, in a global city where it’s accessible to millions.

I think this is partially true.

Would it do much good to return the Moai Statue to Easter Island, which gets 100,000 annual visitors — equivalent to what the British Museum receives every six days — and the island can barely sustain that?

Egypt, on the other hand, is well-equipped to receive its artifacts back. The Pyramids at Giza get twice as many tourists per year as the British Museum does, and they’re building an incredible new museum that could house plenty of the 50,000 pieces the British took.

Also, I dispute the idea that a global city implies that anyone can enjoy them. How does a citizen of Benin see their country’s goods if they’re housed in France? How many Egyptians can travel to London or New York?

In many ways, this repatriation debate is a microcosm of the power dynamics between the colonized world and the colonizers; one where the global north has rarely taken responsibility for its historical actions.

The British Museum is a special, fascinating case here. It has yet to take any concrete steps to address questions surrounding the legitimacy of its collection. It has never repatriated a single artifact, has no plans to do so, and the UK even has a law prohibiting the repatriation of art (though public pressure is mounting to change this).

But change is still possible. Heck, if one Greek newspaper is to be believed, a deal to actually return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece is now at an advanced stage. (We’ll see).

There are no easy answers here. But as one of the world’s most powerful cultural institutions, The British Museum has the resources to strike the right balance between returning objects, and continuing to be a world-class museum.

They have an opportunity to truly lead the way. Let’s hope they have the courage to do so. 🏛

Further reading

- The British Museum Act of 1963 forbids it from removing any object in its collection, except in a few very select cases.

- Protestors interrupted the auction of this $4.2 million mask stolen from Gabon

- The British Museum was recently on the opposite side of things when a spate of thefts resulted in them losing around 2,000 artifacts. It was likely an inside job, with a staff member sacked. The Museum’s director also stepped down after a 2021 investigation was botched.

- Meanwhile, they’ve worked with Google to catalog their entire collection, which you can search.

- Do you live in the UK and have something ancient in your backyard? The British Museum provides an object ID service. But they can’t give an opinion on objects made and/or found outside the UK.

- In 2015, ISIS razed the ruins of the Assyrian city of Nimrud. Now, a race is on to salvage what’s left of the ancient city.

- The International Council of Museums (ICOM) is a borderless organization that establishes ethical standards for museums worldwide

- Woman in Gold is a great film about a Jewish refugee who takes on the Austrian government to recover artwork that rightfully belongs to her family.

- Egypt has massive museum plans of its own. After reclaiming thousands of artifacts, they plan to open a billion-dollar state-of-the-art palace called The Grand Egyptian Museum. It’s set to open later this year, and it will be insane.

Disclosures

- This issue was sponsored by our friends at JKBX.

- Our ALTS 1 Fund has never been asked to return an asset to its home country.

- This issue contains no affiliate links