Hi everyone,

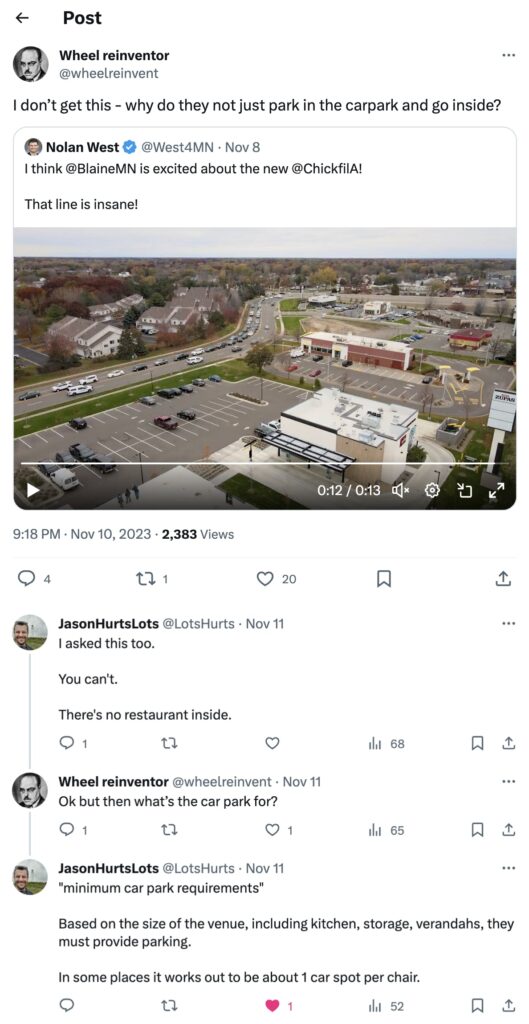

Welcome to the Alts Sunday Edition 👋

I hope you enjoyed last week’s issue on flying car startups.

Today our staff writer Brian Flaherty explores the economics of parking lots.

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

Zoning created America’s parking surplus

Few things get Americans riled up quite like parking.

A quick Google search for parking spot violence turns up dozens of cases where disputes over parking led to stabbings and shootings. And in his recent book, Paved Paradise, author Henry Grabar cites the threats, racial abuse, and physical violence that parking ticket agents are subject to.

The frequency with which people resort to violence over parking tells us something about its paramount importance (especially in the United States). People really care about parking.

That passion only compounds the entitlement many drivers already feel towards parking. Since parking is vitally important, there’s a baseline assumption that it should always be convenient, available, and free.

These assumptions lead to obvious absurdities, like the expectation that people should be allowed to store their private property at no cost on some of the most expensive real estate in the world — as in the case of free street parking in New York City.

But this deeply-held attitude didn’t take root spontaneously. It’s been fostered by the planning and zoning regime, which has both motivated and mandated the creation of cheap, abundant parking.

Two specific policy tools have led to an oversupply of parking in America: parking minimums and property taxes.

Parking minimums

Parking minimums require property developers to build a minimum amount of parking spots for their buildings. (The amount varies based on the type of building.)

These regulations are justified by the idea that if developers don’t build sufficient parking, the people who use their properties will end up parking on the street for free. As the argument goes, developers shift the costs of supplying parking from their own pockets to the public.

This line of reasoning sounds logical. In practice, though, calculations for parking minimums are woefully misguided.

Parking minimums are typically set high enough to provide sufficient free parking during theoretical peak demand — even though parking inherently has a cost (whether paid for by the developer, the driver, or the public) and peak demand is rare (and often not as high as predicted).

The internal logic of these calculations can lead to extraordinarily high minimums. For example, at one point, Seattle required every bowling alley to have 5 parking spots per lane, to satisfy the case in which all lanes are occupied, and all players arrive in their own separate vehicles.

Even without such regulations, though, developers would still be encouraged to supply more parking than necessary, thanks to an unanticipated quirk of the tax system.

Property taxes

In America, property taxes are generally assessed on the property’s market value.

This seems reasonable. Just like a higher salary should incur a larger tax bill than a lower salary, a higher-priced piece of real estate should incur a larger tax bill than a lower-priced one.

However, this surface-level logic doesn’t hold up to deeper scrutiny. Paradoxically, this system punishes property improvements and incentivizes people to hold onto empty plots of land.

Let’s say you own a house and decide to add an extra room. That should increase the value of your home. But in doing so, your property taxes will also rise.

Even if you’re planning to realize that value by selling your home, the payoff could take years. In the meantime, you’ll have to pay higher taxes, which might put you off making the improvements to begin with.

This system helps explain why America’s cities are so full of vacant lots. Since empty land is worth much less than developed land, owners of these lots don’t pay much in tax. And yet, they benefit from the increase in land value that occurs when nearby developments increase real estate demand in the area.

So, how does parking come into play?

Well, if there’s one thing you can use empty land for, it’s parking. Using undeveloped (or minimally developed) land as a parking lot is a popular tactic to generate cash flow without increasing the property’s market value This keeps taxes low and allows owners to await the appreciation in land value that comes from being in a high-demand area.

Slowly, though, things are changing.

As the dangers of too much parking are being recognized, these policy tools are beginning to fall out of favor.

America has a parking surplus

The idea that America has too much parking might come as a surprise. (Who hasn’t been late to an appointment because they were circling the block looking for a spot?)

There’s a huge variation depending on the city. New York City arguably has too few spots, with squeezed curb space and some of the highest private parking prices in the world.

But as a whole, America has far more parking than it needs. Nationally, there are about four parking spaces for every car on the road, even though cars are parked about 95% of the time. Essentially, the total parking stock can never be more than a quarter full.

The perception that parking is scarce largely stems from people’s preference to pay indirectly by spending their time cruising for parking in high-demand areas, rather than paying directly for a parking garage.

While broad data is scarce, a decade-old study found that most private garages in downtown American cities have at least 20% of their spots available, even during peak hours. In lower-demand areas outside of central business districts, free spots are abundant.

One way to understand the scale of parking in America is to see what it would cost to build all the spots from scratch, a concept known as “replacement cost.” Here are the figures for various cities around the country, calculated as the amount each household would have to pay to rebuild all the city’s parking:

- Jackson, WY: $192,000 per household

- Seattle, WA: $118,000

- Des Moines, IA: $77,000

- Philadelphia, PA: $30,000

- New York City, NY: $7,000 (Not a surprise given NYC’s low car ownership rate)

Even once you accept that America has too much parking, it’s not obvious that this is actually a problem.

What’s the harm in having some extra parking? Surely it’s better to have too much rather than too little, right?

What’s the problem with too much parking?

The benefits of additional parking are immediately apparent. The costs, however, lie underneath the surface. And this is why it’s taken cities around the country so long to recognize them.

Here’s a rundown of the big issues associated with excess parking:

Opportunity cost

This is the most obvious issue of allocating too much space to parking; the land can’t be used for anything else.

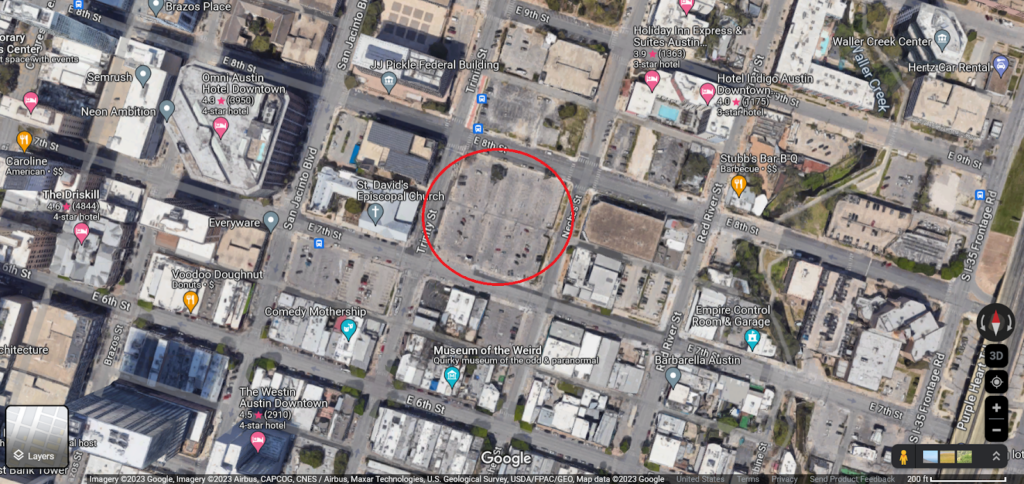

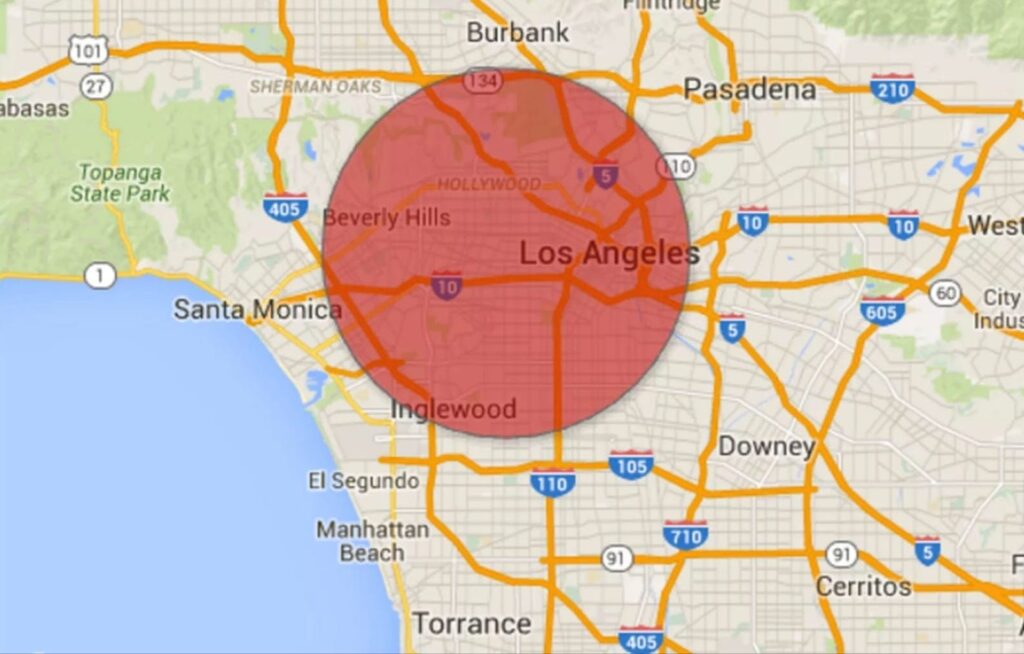

Since parking is dispersed, it’s easy to underestimate the amount of land actually dedicated to it. Here is what it would look like if all of Los Angeles’ parking were agglomerated into a giant circle.

The total land area dedicated to parking in the entire United States, meanwhile, is about the size of Massachusetts. Picture an entire state paved over with asphalt to make room for cars.

It artificially lowers the cost of driving

Oversupplying parking leads to parking that is either free or underpriced. This means drivers don’t actually bear the full cost of driving.

Unless the driver is paying for a market-rate garage, the cost of finishing their trip and storing their vehicle is at least partially borne by consumers (via developers) or taxpayers (via local government). This artificially lowers the cost of driving, leading a higher proportion of people traveling by car.

More cars on the road means higher emissions, accelerating climate change. But another long-term effect is underinvestment in public transit.

Parking lots not only respond to a car-centric society, but further encourage driving, creating a feedback loop toward more driving, more parking lots, and more traffic.

And round and round we go.

It worsens housing affordability

With inflation and interest rates pushing up rents and mortgage payments, housing affordability in the US is at its worst level in nearly 40 years. Parking regulations, meanwhile, lead to fewer units built and more expensive rents.

When developers build units in a place with parking minimums, they need to increase rents to cover the cost of parking construction and maintenance. Adding parking to an apartment can push up the rent by $225. The property tax regime, meanwhile, encourages holding empty parking lots, rather than building new housing on them.

The negative impacts of too much parking don’t stop there. Parking lots can act as heat islands in urban environments, and contribute to more car accidents, which are surprisingly common in parking areas. (My first car accident happened in a parking lot. Anyone else?)

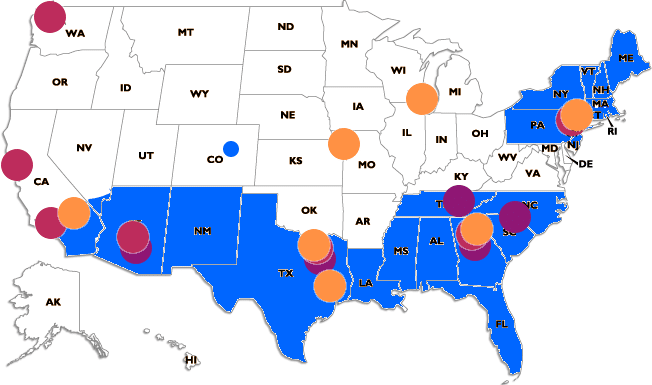

The national parking pushback

Today, frustration with these issues has motivated a nationwide effort to try and dramatically reduce the scale of parking in America.

Rather than start tearing up existing parking spaces, which would cost a lot of money and invite political backlash, cities have taken a more measured approach. The focus has largely been on adjusting regulatory provisions to address the root causes of parking oversupply.

In 2022, 11 cities ended use of parking minimums, including Raleigh and Lexington, KY. This year, that trend has accelerated, with major cities like Richmond and Austin following suit.

Nashville has taken things a step further, enacting parking maximums, creating a cap on the number of spaces developers can build.

Property tax reform, meanwhile, has been much slower. One policy solution to encourage development of empty lots (and, by extension, reduce the supply of parking) is a land value tax (LTV).

An LTV would charge a higher tax rate on the land that a property sits on, while charging a lower tax rate on the property itself. Theoretically, this should discourage land speculation and incentivize productive, income-generating use of property.

Despite the merits of an LTV, the system is used in very few places in the United States. Pennsylvania is the only state government to adopt an LTV, with land taxed at about five times the rate of property. While Pennsylvania’s results seem promising, nationwide property tax reform is likely to be incredibly slow-moving.

Regardless, the changes already in motion are likely to profoundly impact on the parking market in the United States.

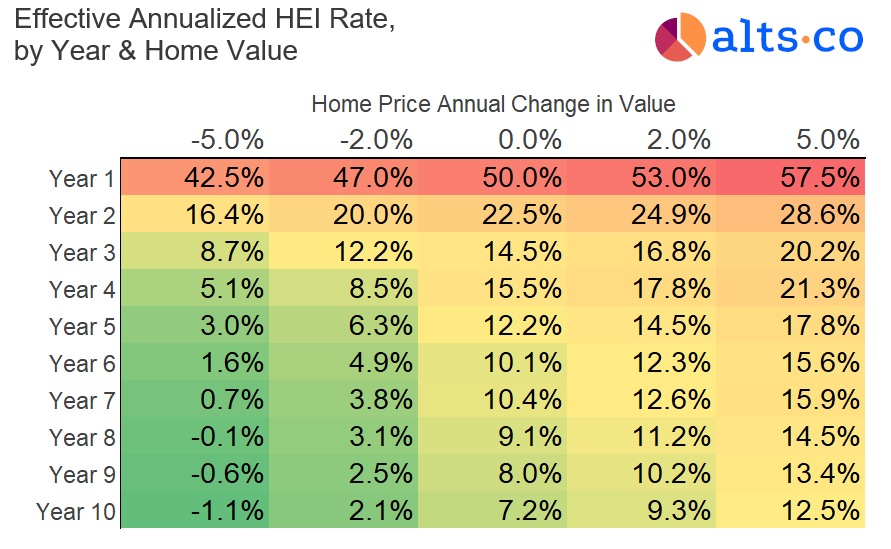

Is now a good time to invest in parking?

Just like you can rent out a house or apartment, you can rent out a parking space. As the pushback against parking takes shape, the time could be right for this oft-overlooked investment.

Cities are ending parking minimums because they recognize the damage caused by free or cheap parking. But this doesn’t mean that parking is coming to an end. Instead, the market will shift to a direct payment model, where high-price off-street parking dominates (rather than low-price on-street parking)

Parking space owners, of course, could benefit tremendously from this adjustment. Previously, governments and developers largely subsidized parking. Now, private operators will largely supply parking at the (higher) market rate.

There are two possible types of direct parking investments: surface lots, and structured parking.

As the name implies, surface lots are just empty plots of land, with a few painted lines, curbs, and speed bumps.

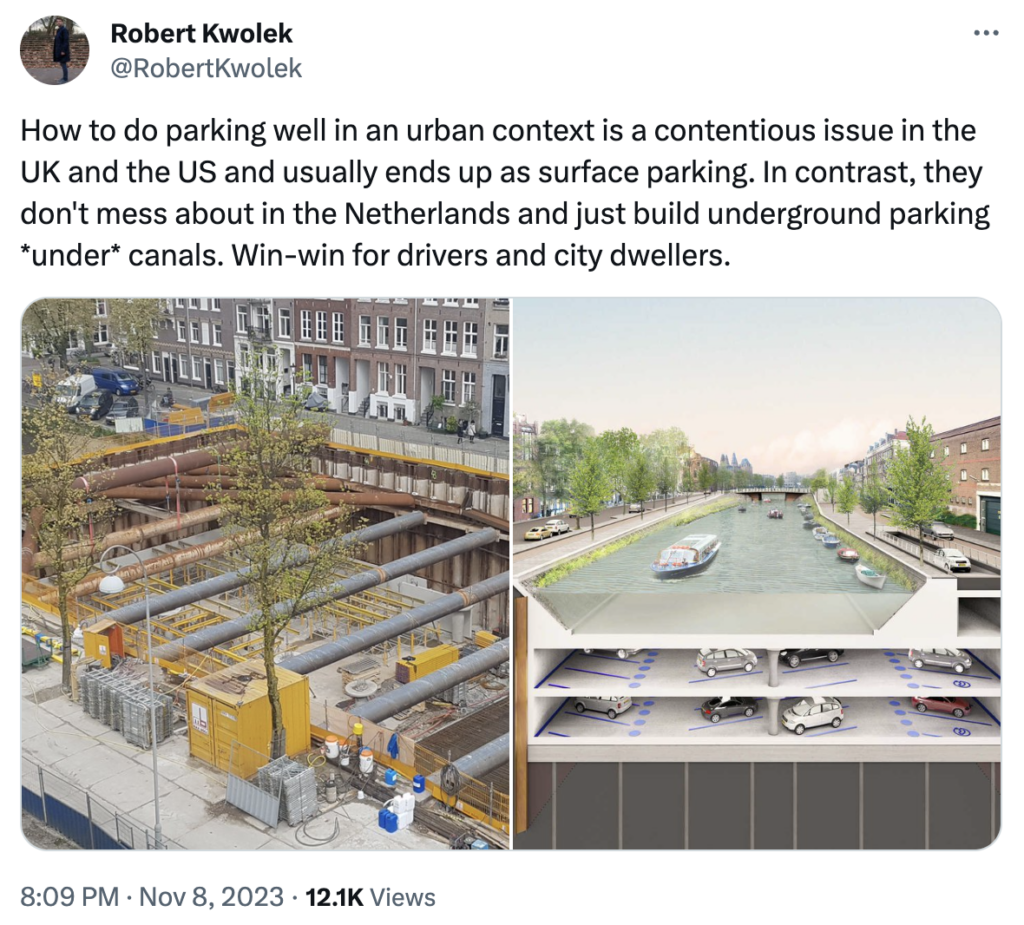

Structured parking, meanwhile, refers to multi-story or underground garages.

As a direct investment, we’ll focus on surface lots. These are cheaper, easier to build, and more accessible to average investors.

In addition to costing less, lots also have the attractive feature of including inherent optionality. Converting an investment from parking into apartments or offices is much easier when you don’t have to tear down a multi-story structure to do so.

Estimates of construction costs per space for surface lots are around $5,000 – $10,000. That might seem high for empty land, but paving, striping, and installing curbs & fences all cost money.

You’ll also need to buy the land itself and spend money on operations — including property taxes, insurance, and access control. Automated ticketing systems often cost more upfront and have weaker enforcement, but paying for attendants incurs higher labor costs.

On average, when factoring in land, construction, and operations, the monthly cost to provide a surface parking space in the United States is about:

- $83 in a suburban environment

- $183 in an urban environment

- and $419 in the central business district of a city

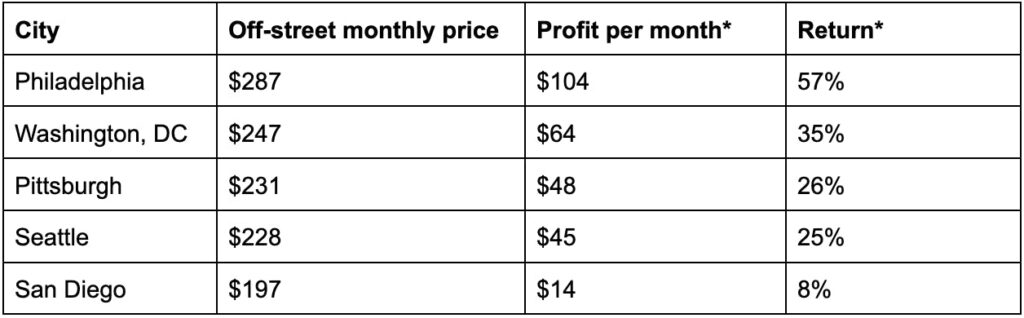

To estimate the yield on a parking spot, we can take the average monthly price for off-street parking in various cities and compare it to the monthly cost of providing that spot.

Here are some figures for three cities in the US:

Obviously, this analysis is inherently limited. The cost of providing a spot in a city is not independent of the price you can charge for parking there.

Moreover, some cities charge high taxes on parking facilities, partially negating or entirely eliminating the property tax benefit associated with lots.

There’s also tremendous variability in scale, with potential investments ranging from renting out just a few spots attached to an apartment building to building a massive parking lot.

If you don’t want to invest in parking lots directly, there are a few ways to get exposure:

- The Mobile Infrastructure Corporation ($BEEP) operates a portfolio of parking lots and garages. Although there are currently some legal issues going on here, so be careful.

- SP Plus Corporation ($SP) provides parking management solutions for operators, an indirect way to get exposure to growth in the paid parking market.

- Sunrise Capital appears to be one of the few investment managers offering private funds focused on parking.

As an investment proposal, parking certainly isn’t flawless. With the growth of ride-sharing apps like Uber, the need for parking may decline. And there’s still such a huge stock of parking spots in America that the nationwide pushback against parking may have less impact on pricing than initially anticipated.

Moreover, while the pursuit of fully self-driving cars has proven more challenging than anticipated, widespread adoption could alter parking demand significantly. A low propensity to pool means that autonomous vehicles will still need to park somewhere, although they could park cheaper in areas farther from the city center, to be called to the owner as needed.

But for the right operator in the right location, investing in parking spaces is certainly an opportunity that’s worth exploring.

Further reading

- NYC parking is so annoying that even Mother Teresa asked the mayor for a special parking permit.

- Frankie Muniz (the kid from Malcolm in the Middle) made millions from investing in parking lots

- The New York Times covered the parking regulation changes sweeping the country.

- A guy on Reddit asked an innocent, naive question: What did “Roman parking lots” look like? But the most upvoted answer was actually quite helpful.

- SpotHero has sold $1b+ in parking reservations, and the younger AirGarage has raised $14.8m for its full-service parking management platform

- This Vox overview shows how a land value tax could help solve housing and parking issues.

- Wyatt wrote about the Chicago mayor who sold the rights to 75 years’ worth of income from Chicago’s parking meters for $1.1 billion to the Kingdom of Abu Dhabi. It turned out great for the Kingdom: They’ve already earned $1.6 billion in 15 years, and still have 60 years to go.

- Australian investment firm QIC is exploring a sale of CampusParc, the long-term owner of Ohio State University’s parking lease, which could be valued at over $850m

- In this interview, the founder of SimCity says he realized if the game allocated as much space to parking lots as they take up in real life, the game would be “very boring”

Disclosures

- Neither the author nor our ALTS 1 Fund holds any interest in any companies mentioned in this issue.

- This issue contains affiliate links to TradingView. If you sign up, we get a few bucks.