Hi everyone,

Welcome to the Alts Sunday Edition.

I hope you enjoyed last week’s issue on investing in rugby. Congratulations to South Africa — Rugby World Cup winners 🏆 (Can’t win ’em all, New Zealand!)

Got a ton of great feedback on that issue, thanks everyone. We’ve got a follow-up piece on the NRFL later this week for those who want to go deeper into their playbook and strategy.

Today we’re returning to the world of litigation finance: a hands-on, nuanced, opportunistic asset class — completely uncorrelated to anything else.

Let’s go 👇

Table of Contents

Join our live webinar next Friday

Litigation finance is an exciting market, but it’s still full of risk.

Viable cases can be hard to find and very risky. If you lose the case, you can lose all your money, period.

Fenchurch is two steps ahead. They mitigate this risk by taking a totally different approach than everyone else — they structure litigation funding as a secured loan.

They work with law firms, providing funding for their (enormous) pre-litigation expenses and court fees. (Something known as disbursement funding).

They don’t touch big, landmark cases. Rather, these are high-volume, low-value consumer claims backed by strong legal precedent, and provide a fixed return — giving you much more security and diversification than traditional litigation finance.

Before funding disbursements of any claims, an “ATE (after-the-event)” insurance policy is taken out. The policy costs a bit upfront, but get this: If the law firm loses a case, the insurance policy covers the disbursements and repays Fenchurch in full.

Unlike traditional litigation finance companies, Fenchurch earns the same return on every case – win or lose and is not dependent on its success.

Join our live webinar

Join our live webinar next Friday, Nov 3 at 2pm EST.

Litigation finance doesn’t have to be risky. Hear directly from Louisa Klouda and Matt Haycox, litigation finance experts and founders of Fenchurch Legal about the smarter way to invest in this space.

You’ll learn:

- The pros & cons of “normal” litigation finance

- How to mitigate risk in litigation finance

- A smarter way to invest in this space (that nobody is talking about)

- How to get simple, fixed-income returns

What is litigation finance?

Pretend you run a small manufacturing company, and you just signed a contract to sell your specialty tools to a big corporation.

This should be a huge moment for you. The customer is a Fortune 500 company, and the anticipated revenue from this deal will allow you to expand your manufacturing capacity. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, one day, the company check rolls in, but it’s for an amount significantly lower than you agreed upon.

You call the company, furiously demanding to know why they violated their contract. The company disagrees, and instead of offering a good explanation, they basically say, “Sue me.”

Of course, the company is betting you won’t sue them, for one frustrating but obvious reason: going to court is incredibly expensive.

Legal fees alone average more than $300 an hour — and far higher when specialized attorneys must be brought in. For small businesses and individuals bringing cases against opponents with deep pockets, these costs can be prohibitive. Many SMBs would just eat the loss and move on.

But hang on a minute. Now you have a situation that requires capital upfront (legal fees) in return for a potential big payoff (the payment plus damages).

Can financing legal claims be an investment opportunity? You bet.

The financialization of legal claims

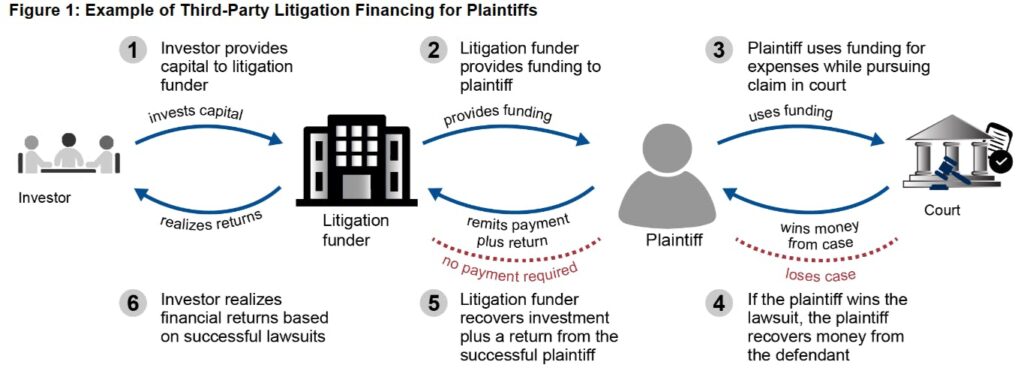

Much like how an investor can bankroll a company in exchange for a slice of the profits, an investor can bankroll a lawsuit in exchange for a slice of the winnings.

And like any other investment, investing in a lawsuit can be risky! If the lawsuit fails, the plaintiff (the one suing) typically doesn’t have to repay the investor. (“Thanks for paying my lawyer’s fees. Sorry we lost. Tough stuff”)

This dynamic creates an incentive for investors to only fund claims that have a good chance of winning.

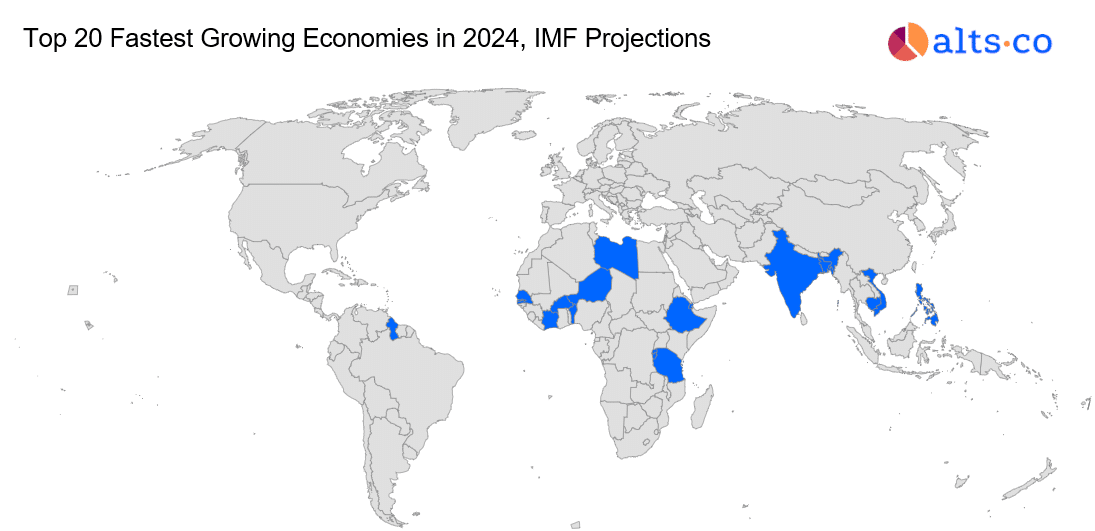

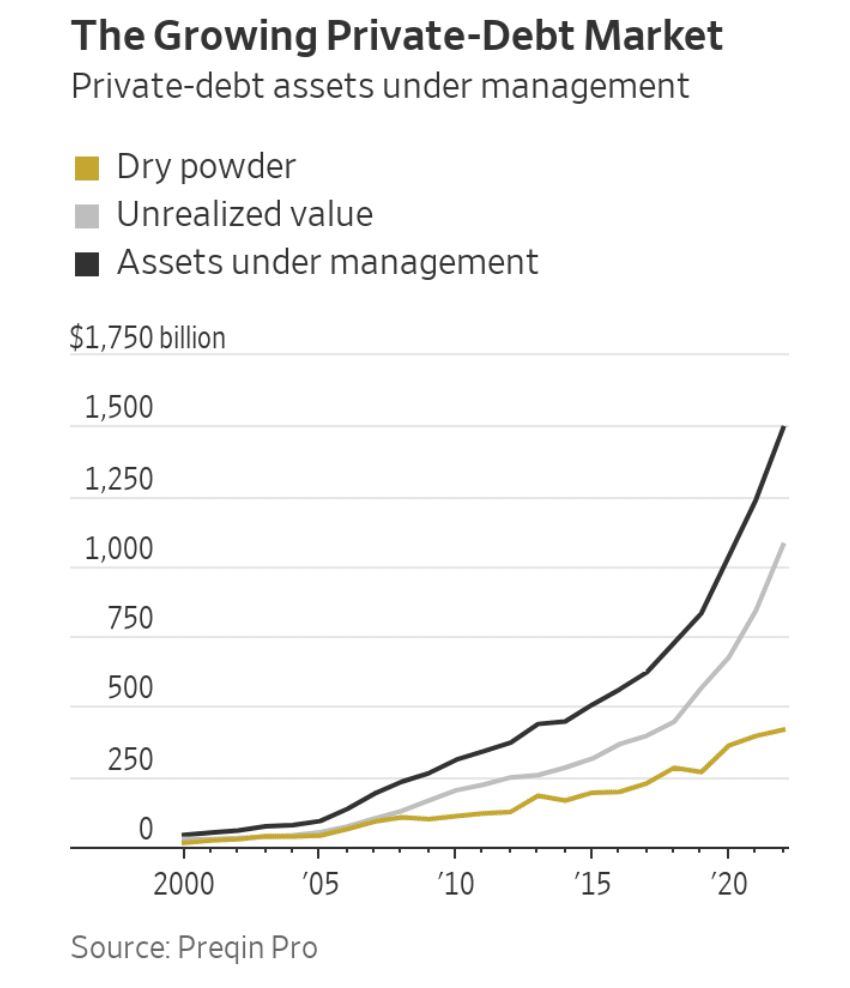

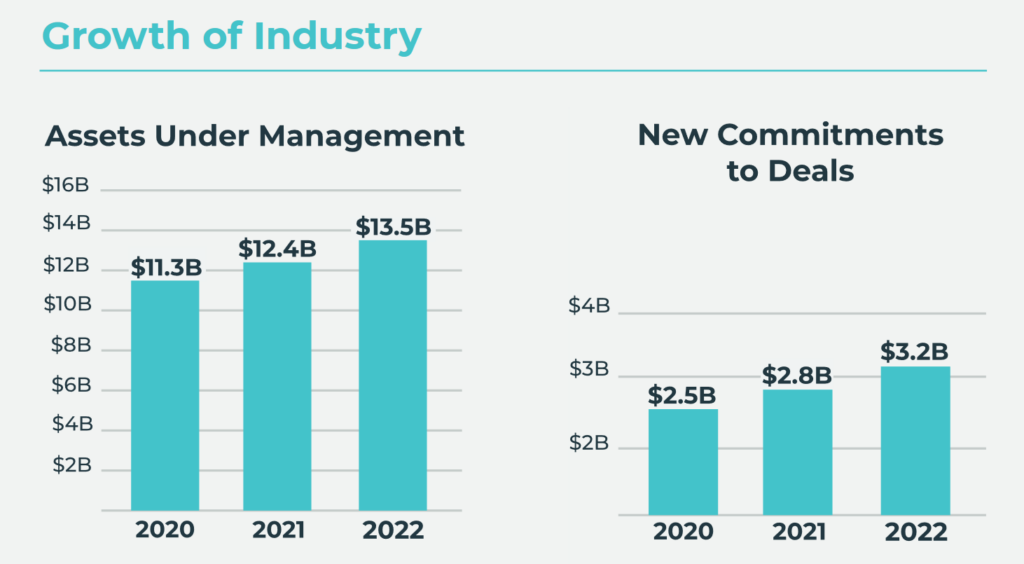

Over the past decade, the litigation finance industry has taken off:

Compared with other alternative asset classes, litigation finance is still relatively small. But as the market has grown, it has evolved to meet the diverse needs of plaintiffs, lawyers, and financiers.

Today, there are three main forms of litigation finance.

Why is litigation finance needed?

To understand the different forms of litigation finance, we have to start with a fundamental question:

Why is litigation finance necessary in the first place?

Yes, we just spent the previous section outlining how the practice can help plaintiffs with legitimate claims but limited resources. But historically, that need has been met through something called contingent compensation.

When a lawyer takes a case “on contingency,” they agree not to charge anything upfront, and only get paid if they win. This structure is also referred to as “no-win, no-fee.”

On the surface, this would makes litigation finance redundant. Why does the industry exist if lawyers are already doing this?

But contingent compensation isn’t a perfect system, and isn’t always viable for all cases.

Plaintiffs need better options. So three types of litigation finance have popped up & answered the call.

Commercial plaintiff financing

In commercial plaintiff financing, funders (i.e. investors) provide businesses capital to pursue financial disputes in court. An example would be the initial situation we outlined, where a small business sued a much larger company for contract violation.

In these cases, investors must do extremely thorough due diligence to ensure a claim is viable and has a good chance of winning. (In fact, that’s one of the reasons why the contingency structure isn’t suitable for many commercial cases.)

Breach of Contract and IP cases are expensive, and plaintiffs need millions of dollars to win them. Some litigation finance investors pay for the case in hopes of a slice of the winnings.

Commercial plaintiff financing is a hands-on investment. Investors devote a huge amount of time to figuring out which cases have merit and which don’t. It’s practically their entire job!

In contrast, lawyers might struggle to justify devoting the time needed to evaluate a case on contingency (for which they won’t be paid) when they could be working on non-contingent cases (for which they will be paid).

Further, businesses may want to use funding from litigation investors for expenses other than legal bills (so long as doing so is allowed under the agreement).

Since contingency agreements only cover legal bills, they’re not suited for firms that need help covering operating expenses while waiting for the suit to end.

Consumer plaintiff financing

In consumer financing, the plaintiffs are individuals rather than businesses.

Compared with the commercial cases, funding amounts in consumer claims are significantly lower; usually between $1k-$10k. The most common case types here are personal injury and consumer harm.

Many lawyers can and do work on contingency for these types of cases. But if you’re picturing Lionel Hutz-style ambulance chasers, you’re wrong. These are mostly boring, procedural cases. Stuff with clear protocols in place. We mostly know how they’ll end. Due diligence is less of a barrier.

Claimants may also choose to turn to litigation funding to cover non-legal bills. In personal injury cases, for instance, plaintiffs may need to pay for medical or living expenses, especially if the injury has left them unable to work.

Again, this is where litigation finance shines.

Law firm financing

But just because a consumer hasn’t used litigation funding for their case doesn’t mean they aren’t benefiting from it. The last type of litigation finance occurs when lawyers themselves turn to investors to get funding for their own cases.

See, most lawyers don’t actually run their own firms. Instead, they’re hired as employees at a larger firm.

This creates a sticky issue for law firms that take on contingent cases — they only get paid if a case is successful, but in the meantime they still need to pay their lawyers!

You may think all lawyers are rich, and law firms are flush with cash. But that’s not quite how it works. Just like consumers have ongoing bills to pay while they’re suing a company, so do law firms!

Sound familiar? This right here is the exact problem litigation finance is designed to solve.

Contingent compensation doesn’t address the fundamental cash flow mismatch between needing to pay lawyers now and only receiving winnings from the lawsuit in the future. It just changes who experiences that mismatch.

In a nutshell, individuals who can’t go out of pocket for legal expenses basically have two options:

- Find a lawyer to work on contingency or

- Turn to a litigation funder.

But lawyers working on contingency also have their own decision to make – whether to eat the cost of litigation upfront, or work with a litigation financier to help pay the bills.

In law firm financing, investors fund law firms directly, based either on specific cases or a portfolio of similar cases. Funds are used to pay normal operating expenses while the case is ongoing. If the law firm wins on behalf of the plaintiff and earns their contingent fee, investors get repaid their initial outlay, plus an agreed-upon return.

The industry’s unique quirks

As you can see, the basics of litigation finance aren’t actually that complicated. Investors pay for the legal expenses in exchange for a cut of the winnings.

But underneath the surface hides a world of complexity. Litigation finance has its roots in courtrooms, not markets. As such, some of the features of this asset class can be quite unique.

Here’s why:

It’s both equity and debt (sort of)

It’s usually easy to tell whether a financial asset is equity or debt. Investing in, say, tequila is owning an asset, whereas investing in something like private credit is holding debt.

Legal investments, though, tend to combine features of both. It’s sort of in-between.

Litigation funding agreements are often styled as “loans,” because investors are providing capital upfront that needs to be repaid. But unlike normal loans, litigation loans have no fixed interest rate or maturity date.

Oh, and the loans are often non-recourse, meaning the lender (investor) can’t pursue the borrower (plaintiff) for repayment if the lawsuit fails (which it often does).

This all makes litigation funding look an awful lot like equity. But these agreements also tend to contain provisions associated with debt, such as financial covenants or the posting of collateral.

If the funding agreement comes under scrutiny* from the court during the lawsuit, it can really matter whether the investment is characterized as debt or equity. As we’ve discussed, there are a lot of regulations surrounding this stuff, including state laws, usury statutes, and rules governing legal ethics.

That’s not to mention the tax implications resulting from the characterization of the agreement.

Due to this hybrid nature, direct investors in legal claims risk seeing their investment recharacterized — a fancy term for when you think an agreement falls under one category (like debt), but a court disagrees, characterizing it under another category (like equity).

(* Recently, there has been a bunch of scrutiny over litigation finance agreements in the UK. They have been claiming that if the financier is taking a % of the winnings, it could be classed as a DBA (damages-based agreement) and should be regulated by the SRA. This is another reason the fixed rate from Fenchurch is a better model.)

Outcomes are black & white

A binary bet is one in which you either win or lose. It’s black & white, like flipping a coin. There is a clear winner and loser.

Litigation finance isn’t purely binary – but it’s much closer to it than other investments are.

Take stock investing, for example. When you buy & sell stocks, it’s not always easy to tell whether you “won” or “lost.” If you bought a stock and sold it when the price soared 20% in several days, that might feel like a victory. But if the stock continued to climb much higher, you lost out on a lot more money (your investment had a high opportunity cost of selling too early)

The potential outcome of most investments looks is a distribution of returns, some of which are better, and others worse. But it’s all relative; it’s all on a scale.

In contrast, litigation finance comes with one winning outcome and one losing outcome. Either your side wins the case, or they don’t.

Yes, within victory, there could be a range of returns — especially if the funding agreement specifies that an investor receives a portion of the awarded recovery. But losing the lawsuit usually means an investor gets nothing back.

Even venture capital isn’t as black & white as litigation finance. People think an “exit” is a black & white sign of success, but there are plenty of cases where a company exists and VCs lose money! A win is not necessarily a win.

In this sense litigation finance is probably most similar to the Event Contracts offered by prediction markets like Kalshi.

There’s some collection risk

When investors consider funding a case, they have to think carefully about the facts involved, the merits of all the arguments, and the potential winnings the plaintiff could be entitled to.

But there’s something else they need to consider: whether the defendant will actually pay!

Even if a court has awarded the plaintiff a sizable amount of money, investors could end up not seeing a penny.

This isn’t just a matter of solvency – companies will frequently engage in legal trickery to avoid paying large lawsuits. Consider the “Texas two-step,” in which a firm allocates legal liabilities to a separate, spinoff company, only for the new company to declare bankruptcy. Fun stuff!

This type of risk is exceedingly rare in other markets. Imagine executing a successful stock trade, only for your brokerage to refuse to wire you the money when you asked for it.

Pros and cons of litigation finance

While still small compared to mainstream asset classes, litigation finance is growing rapidly. Forecasts indicate a market growth rate of around 9% for the next 5 years, resulting from increased demand for litigation funding services and an increased supply of investor funds to provide those services.

For investors, litigation finance comes with a distinct combination of attractive features. But navigating any emerging asset class isn’t easy. Let’s look at the pros and cons.

The Pros

- High returns. Data is a bit sparse since this asset class has no centralized market. But research indicates very high returns for litigation finance investors, often over 20% annually. Yeah.

- Uncorrelated to broader markets. Huge diversification benefits are one of the biggest draws to litigation finance. This asset class is fundamentally uncorrelated to almost any other market. Deciding the merits of a legal case has essentially nothing to do with the broader economy or other markets.

- Greater investor control. As investment markets get more and more competitive, it becomes exceedingly difficult to find an edge by studying fundamental or statistical information. It’s early days for litigation finance, which means legal expertise can still add huge value by deciding which cases to fund and which to ignore. This added room for due diligence and research can be an excellent source of alpha, something hard to achieve in other asset classes.

The Cons

- Litigation risk. Obviously, to be a successful litigation funder, you need to back winning cases. On the surface, the industry’s win rate is very high – reports indicate that litigation finance-backed cases are lost only 10-15% of the time. But when you consider that losing cases often results in a complete zeroing of the investment, it’s not hard for a higher-than-expected loss rate to start eating into returns.

- Illiquid. While the liquidity of a specific litigation finance investment will vary, in general, it’s difficult to sell these assets before maturity. This has some benefits (namely, an illiquidity premium), but can limit investor options to cash out early.

- Regulatory risk. The laws surrounding litigation finance continue to evolve. While the broad trend has been to loosen restrictions over time, that may reverse, particularly if there’s public blowback to perceived “predatory” funding practices.

Investing in litigation finance

As an emerging asset class, avenues to invest in litigation finance are limited. With that being said, several high-quality options have emerged (and one that’s really unique).

LexShares

LexShares offers accredited investors access to the commercial litigation finance space. Their team vets and underwrites these opportunities before offering them on their platform for investment.

LexShares also offers intermittent fund opportunities, which invest in a portfolio of legal cases.

Burford Capital

Burford is the only litigation finance firm to be publicly listed (NYSE:BUR), which could make them suitable for investors with liquidity concerns.

However, betting on the equity performance of a litigation finance firm may be a less direct way of gaining exposure to the fundamentals of the cases that make up the asset class.

Fenchurch Legal

Fenchurch is a specialist litigation funder based in the UK, open to investors from around the world.

Most of the litigation finance market is made up of lenders making risky unsecured loans. Fenchurch takes a different approach, offering fixed-rate secured lending directly to law firms.

Fenchurch lends to these firms to fund specific pre-trial expenses – but only those with small-ticket consumer claims. These are highly procedural affairs with strong legal precedents. The law firm wins or settles the vast majority of these cases, then repay Fenchurch from the winnings.

But here’s what’s special about Fenchurch – they only take cases backed by an insurance policy (“known as ATE”. This is a huge deal. It means even if the law firm loses the case, the insurance policy will still pay out, ensuring Fenchurch earns the same return regardless of what happens.

With this approach, Fenchurch captures the high returns associated with litigation finance, but dramatically reduces the risk by only participating in secured lending.

Fenchurch is also focused on simplifying the litigation finance process for investors. To that end, they’re currently offering two fixed-income products: a 2-year note yielding 11%, and a 3-year note paying 12%.

Join our live webinar

Join our live webinar next Friday, Nov 3 at 2pm EST.

Hear directly from Louisa Klouda and Matt Haycox, litigation finance experts and founders of Fenchurch Legal about the smarter way to invest in this space.

You’ll learn:

- The pros & cons of “normal” litigation finance.

- How to mitigate risk in litigation finance

- A smarter way to invest in this space (that nobody is talking about)

- How to get simple, fixed-income returns

Closing thoughts

Earlier in this issue, I asked if litigation finance should be considered equity or debt?

But the more I think about it, the more I realize it’s neither of these.

To me, this feels like a form of highly educated betting.

Precedent is a huge part of this world. If you understand precedent, you get a better handle on probability. Deciding which cases to finance is a bit like betting on a founder, but with less luck. It boils down to experience and understanding the law.

But this asset class can be contentious. Allowing people who are completely unrelated to a legal claim to share in the winnings makes some people deeply uncomfortable.

And there’s some justification to this argument – the law should be based on the pursuit of justice and truth, rather than profit.

And you know what? That’s exactly why litigation finance needs to exist.

Letting investors bankroll plaintiffs allows cases to be decided based on their virtues in court. The alternative is for such cases to never be brought in the first place! (or to end early thanks to rapidly mounting legal bills)

The legal world is starting to understand that finance has a part to play here. Historically there. have been restrictions on this practice.

But the pro-litigation financing argument has been gaining favor among judges and regulators. Now, restrictions are being relaxed.

Like so much else in law, movements happen gradually, then suddenly. Litigation finance is no different. ⚖️

Further reading

- I don’t agree with all of the takes in this NYSBA piece, but it comes out swinging

- This Milken piece is a much better, condensed version of the ethics around litigation finance.

- Litigation finance has a fixed-rate model nobody is talking about. Learn more at our webinar next Friday

- In this case, a litigation finance investor got in trouble due to disagreements about whether the investments were ultra-high-interest loans (illegal) or a purchase of future receivables (closer to equity, and legal)

That’s a wrap!

Thanks to Brian Flaherty for researching the first draft of this issue. And of course to Louisa Klouda and Matt Haycox from Fenchurch who, in typical legal fashion, marked up our draft with about five hundred footnotes 😀

What do you think? Are you intrigued by this world? What questions do you have about this stuff? (Louisa and Matt will answer in the webinar). Do you work in law? What did we miss?

Let us know, we love hearing from readers.

Until next time, Stefan

Disclosures

- This issue was sponsored by Fenchurch

- Neither the author nor our ALTS 1 Fund holds any interest in any companies mentioned in this issue

- This issue contains an affiliate link to Kalshi