Recently, while on a short trip to Morocco, I had the pleasure of making friends with a fantastic tour guide. While showing me around the ancient city of Fez, he asked what I do for work, and began to talk about how lending money works in Islamic countries.

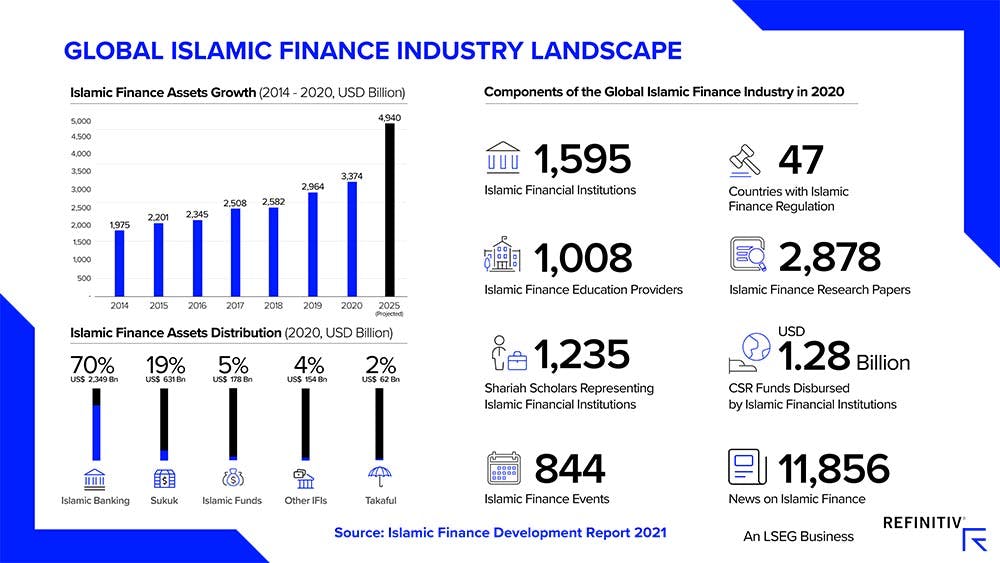

Next Saturday, Muslims worldwide celebrate Eid al-Adha, which was described to me as “like Christmas for us.” In the spirit of Eid, we are dedicating this issue to Islamic finance. It’s only been around for a cool 1,300 years, and is now a sector holding $3.2 trillion in global assets. So what exactly is it all about?

Let’s find out 👇

Table of Contents

What is Islamic Finance?

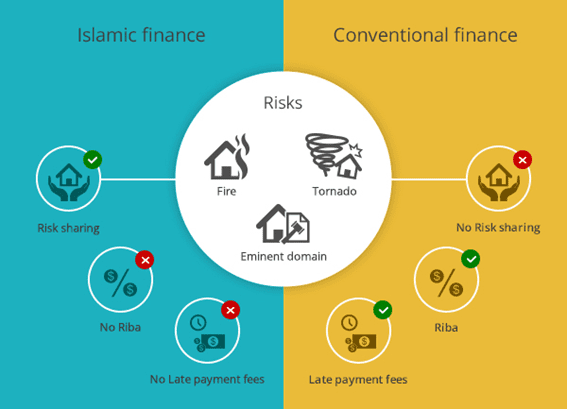

Islamic finance is a set of financial rules that adhere to Sharia law, based on the teachings of the Quran.

It views money uniquely, taking strong stances on fundamental concepts such as:

- Speculation & risk

- Fairness & justice

- Protection of the weak and vulnerable

- The connection between finance and the real economy.

This is all done as an attempt to prevent exploitation and reduce inequality.

Principles of Islamic Finance

There are a few key principles to understand:

- Gains from interest are prohibited. This is the biggest one. Lenders are not allowed to collect interest or profit from interest on loans.

- A focus on altruism. Any interest, dividends, or other returns from lending capital must be donated to charity.

- No derivatives. Financial instruments deemed too intangible, or not part of the “real” economy, are banned.

- Prohibited industries. Businesses are prohibited from engaging in specific enterprises, including gambling, alcohol, pork, pornography, and weapons.

- No excessive risk. Investments with a high degree of uncertainty, or gharar, are not allowed. All possible risks and relevant info must be identified to investors. Islamic finance also prohibits selling something one does not own, since it introduces the risk of its unavailability later on.

Critically, Islamic finance is not just for those who follow Islam. Given the global economy, it’s for anyone wanting to do business with any of the 80 countries participating in its economic principles.

A short history of Islamic Finance

Islamic finance dates way back to the 7th century — a full 900 years before the first incarnations of capitalism.

Since then, the most controversial topic within the community has been how to define what is known as riba.

What is riba?

Riba is the foundational concept at the heart of Islamic finance.

Riba means “increase, addition, or growth,” and usually refers to any excess value above the original amount (i.e., the increased cost of a loan over time due to interest payments.)

According to the Quran:

O believers, take not doubled and redoubled interest, and fear God so that you may prosper. Quran, verses 13-132

In the opinion of most Islamic scholars, riba is considered an unjust increase — with compound interest considered the most harmful and dangerous of ribas.

In a nutshell, Islamic law views interest payments as a relationship that vastly favors the lender. Since it doesn’t consider money an asset, but rather a tool for measuring value, it dictates that money must not be allowed to create more money.

Modern incarnations of riba

In the early 1960s, the Islamic world was transformed by oil money.

Four of the five founding members of OPEC are Islamic countries (Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia), and the need to invest serious money in a Sharia-compliant way suddenly became very important.

But it is widely agreed that modern Islamic banking began with the MGISA, or Mit-Ghamr Islamic Saving Associations. MGISA was founded in Egypt in 1963 to invest people’s savings in a manner compliant with Sharia law.

Fast-forward to today, and the rule of Islamic Sharia law still applies. Receiving or paying interest is a major sin. In fact, not only are Islamic banking institutions not allowed to charge interest, they are not allowed to offer a return on deposits.

So if they cannot collect interest, how do they make money?

How do Islamic banks make money without interest?

Non-interest banking

On the consumer side, banks get around riba by providing a “service” to earn profits, in what is known as non-interest banking.

In non-interest banking, a customer is not just a bank’s customer, but also a partner. They own assets together in a joint-ownership structure where both parties share the risks as well as the profits.

Instead of creating a loan, Islamic banks purchase assets with their customers’ money at an agreed-upon increased price, and provide a bank account that offers a profit/loss on each investment. An interest-free loan contract is then created to facilitate these mutually agreed price & repayment terms, in what’s known as a Sukuk.

This is how financing for homes, cars, and businesses works across the Muslim world. Companies like Lariba offer “riba-free financing,” where each financed asset has two rights of ownership:

- The first is the ownership of title to the property

- The other right is the right to use the property

For example, a bank can own a house but rent out the right to use the house.

Profit sharing

On the business side, equity financing of companies is both allowed and encouraged (as long as the company is not engaged in a restricted industry).

At first glance, Islamic financing of businesses looks a bit like venture capital. Banks succeed when the businesses they invest in succeed, and if the underlying business fails (or fails to grow), the banks take it on the chin.

But since borrowers give banks a share in their profits rather than paying interest, it’s more similar to a non-dilutive revenue-based financing arrangement.

Note: Revenue-based financing has been around for ages, but it has recently gained some serious steam. Dru Riley just wrote a great piece on RBF, and Tractor Ventures is a terrific example of a company doing this.

Other Islamic Finance principles

Islamic financial principles have created some philosophical issues that Islamic thinkers grapple with.

Harris Irfan, a co-founder at Deutsche Bank Islamic Finance and author of Heaven’s Bankers says:

[Islamic Finance] principles are hugely disruptive, since they are radically opposed to both Keynesian economics and monetarism. As a result, one cannot make money out of money, which means that while interest is forbidden, money also cannot be created in a fractional reserve system through the act of lending.

But understanding Islamic finance means understanding that the principles go deeper than just riba.

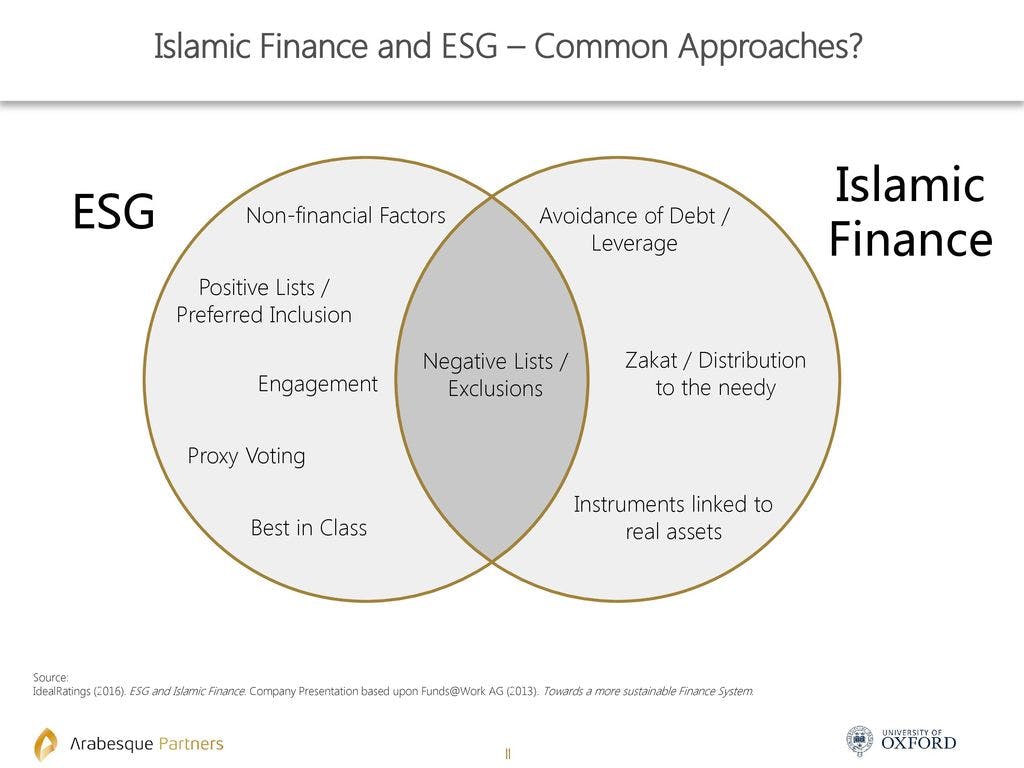

Islamic finance principles have much in common with ESG principles (which is no stranger to controversy itself). ESG investments are generally known as “socially responsible investing.”

But Islamic finance takes on the added dimensions of shared risk and profit & loss sharing. As stated above, lenders are more like partners in a venture, with both parties sharing the full risk of a potential loss.

Let’s go deeper into Islamic finance from the perspective of personal finance and corporate finance.

Islamic personal investing

There are four types of personal finance arrangements: Ijara, Murabaha, Wakala, and Musharaka

Ijara

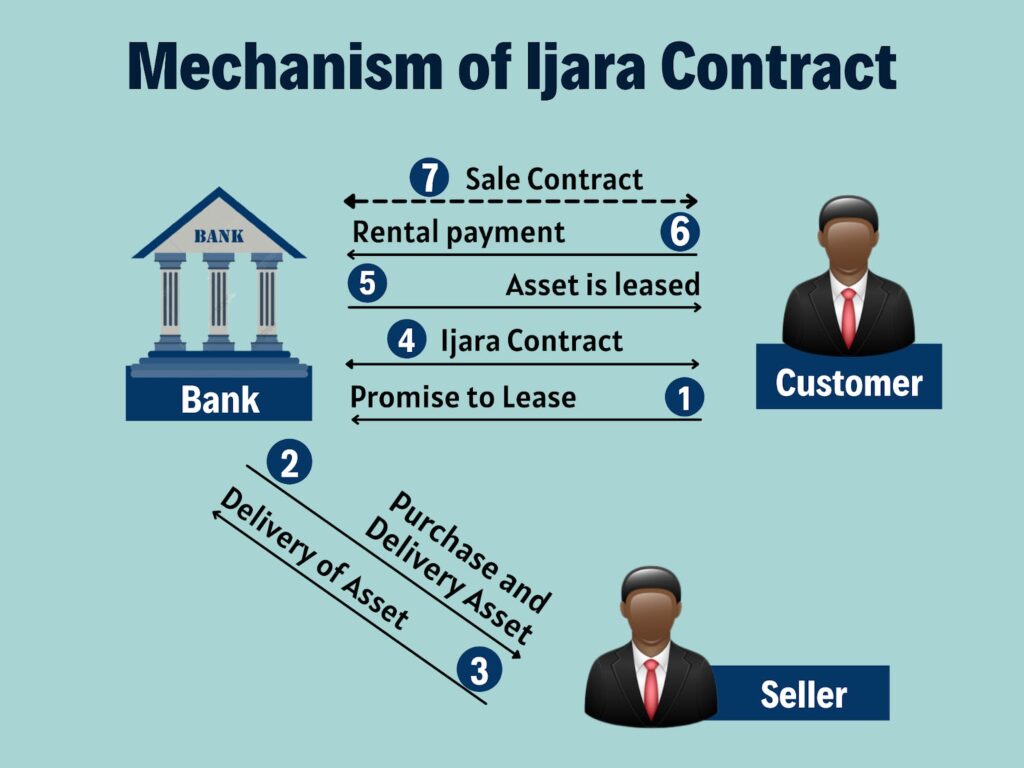

Ijara is basically a lease. A bank buys an asset outright and then promises to lease it to a customer. As opposed to creating a creditor-debtor relationship, ijara creates a lessor-lessee relationship.

Over time, the lessee makes principal repayments in a “diminishing musharaka,” similar to an amortization schedule. At the end of the lease, the lessee can buy the home outright from the lessor.

Murabaha

Similar to ijara, a murabaha loan occurs when a bank purchases an asset at a mutually agreed price that includes a markup. The lender buys the asset at the inflated price, and creates a loan for the full amount. After the last loan payment, the customer becomes the asset owner.

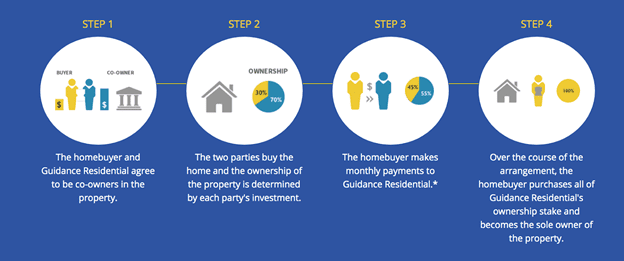

A bank buys a home and leases it out to tenants. A portion of the tenants’ monthly payments go to the bank, and a portion to an account the tenants can use if/when they wish to purchase the home.

For example, let’s say a bank and a homebuyer agree to buy a home worth $300k. For the bank to make money, they both agree that the homebuyer’s loan price is $375k (hypothetical). The $375k, and not a penny more, is what the homebuyer is responsible for paying over a 30-year amortization schedule.

In this way, no interest is paid. And until the lease ends, the homebuyer is legally considered a renter.

And here’s where it gets really interesting: At the end of the lease, the bank must allow the renters to purchase the home with their accumulated credit. Unlike with traditional home loans, however, the renters are under no obligation to buy the house! So if the renters decide not to buy the home, the bank must sell it and distribute proceeds to the previous renters.

If this all seems like a form of hidden interest, in many ways it is. Islamic finance has developed some creative workarounds for riba. But consider how important it is for Muslims to have avenues that ensure they are faithful to governing laws.

Wakala

Under a wakala agreement, a customer allows a bank to act as its agent, allowing the bank to invest money for them in Sharia-compliant trading activities — which is crucial for their retirement.

These Sharia-compliant activities go deeper than riba. Remember, any money received in the form of interest must be donated to charity.

The donor must make clear that the donation money is interest money and not zakat (annual religious charitable payment) or sadaqah (voluntary charity). The charity that you donate to cannot just go and build more mosques; it must use the money to directly relieve hardship and poverty.

Musharaka

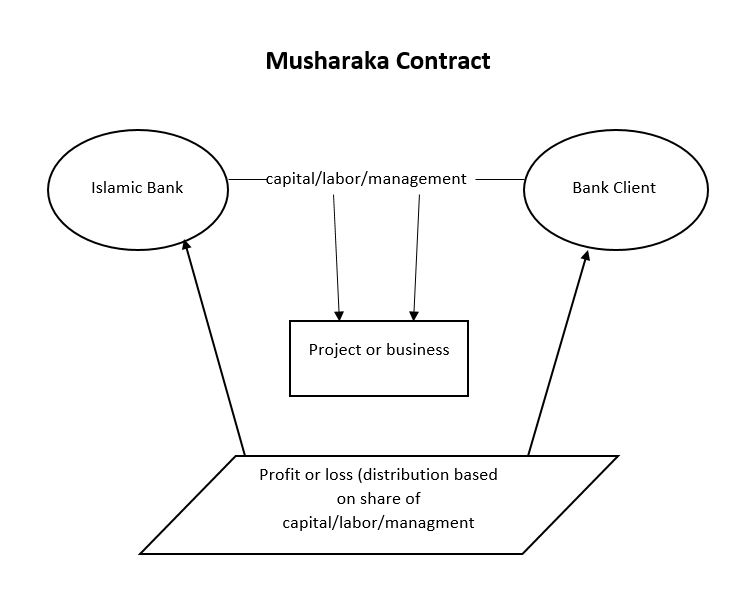

Musharaka is another joint venture where the customer and bank contribute funding an investment and agree to share the returns. The risk proportions are decided in advance.

This is the scheme Islamic finance advocates are often most excited about. Musharaka is essentially a form of revenue-based financing, which can be especially useful in underdeveloped countries. It’s also considered the purest form of Islamic finance.

Under musharaka, small businesses can work without worrying about interest repayments leading to crushing debt, and everyone has skin in the game.

Islamic corporate investing

Deutsche Bank, Citibank, and HSBC started their Islamic divisions in the 1990s, but the rise of Islamic banks on Main Street is a rising trend. 25 Islamic financial institutions now operate in the US, including American Islamic Finance House and UIF.

But how do these institutions decide what industries to invest in? (Or what not to invest in?)

We know industries like pork, arms manufacturing, and gambling are a big no-no. But some industries are a gray area. Media is a perfect example. Investing in a news company might be permissible, but a movie production company wouldn’t be if a “significant portion” of their output is considered inappropriate.

There are also financial prohibitions. Non-Islamic financial services companies are out, and all companies must meet certain criteria concerning interest-bearing debt. Most scholars have accepted that companies need less than 1/3rd of their market cap in interest-bearing debt to be compliant.

Parallels with ESG

Given the recent hype & capital flows into ESG, there is some push to “ride the wave” and align Islamic financing with ESG.

There is already some overlap between ESG investing and Islamic finance. But ESG investing typically comes from a starting point of inclusivity, while Islamic financing often does not.

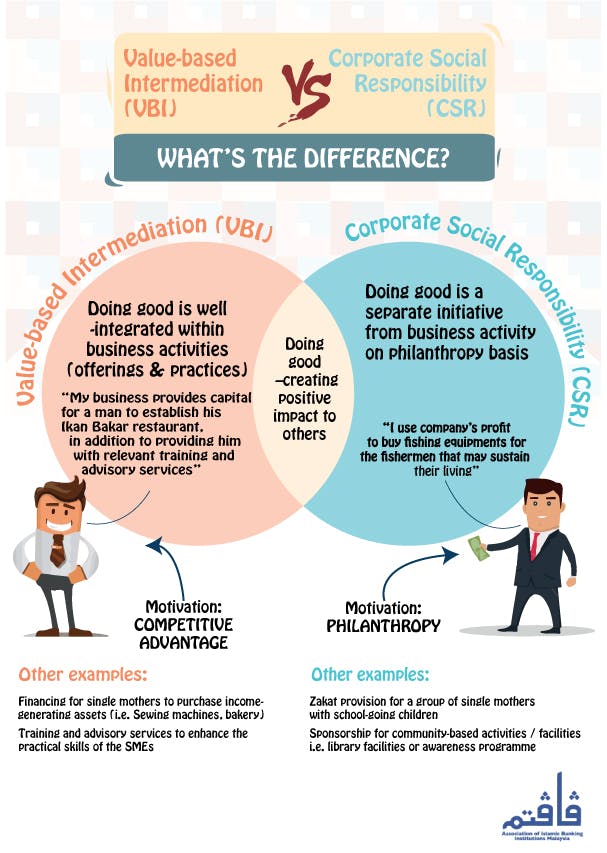

To help navigate this, Bank Negara Malaysia has developed an investment framework called Value-Based Intermediation, or VBI.

VBI promotes real economic activities that result in positive social and environmental outcomes. VBI is Sharia compliant and also integrates more ESG components.

Harris Irfan notes:

There has been some discussion in recent years that Islamic banks should take a more active role in emphasizing positive filters — especially ESG-related. To date, they have been slow to respond in this area, with the exception of the Malaysians.

Criticisms of Islamic Finance

Islamic finance certainly faces its challenges.

On one hand, Sharia law’s rules against investments in derivatives prevent excessive risk-taking. This is a reason why Islamic banks survived 2007 relatively unscathed (though they were still exposed to declines in real asset prices and went into recession anyway.)

However, because loans are joint ventures, far more time & money is spent on customer due diligence. These costs are ultimately borne by both parties, resulting in higher costs for everyone than traditional interest-bearing instruments.

Others point out that the convenient riba workarounds aren’t so convenient after all, and just create unnecessary steps that achieve basically the same thing as interest would.

But perhaps the biggest problem is that riskier projects can’t get funding if they don’t meet traditional benchmarks. Any VC will tell you that being too conservative with your investments is a slippery slope towards mediocrity. Some of the Islamic world’s best & brightest feel they have no other choice but to look elsewhere for financing.

An important example of this is student loans.

Islamic finance and student loans

Access to student loans is especially difficult for Muslim students.

Aside from housing, college is the biggest expense most people ever have. Student loan debt in America is now $1.75 trillion — nearly twice the size of credit card debt. But it is forbidden for Islamic students to take on interest-bearing loans, and Islamic financial institutions offer almost no solutions for this.

Currently, Muslim students are encouraged to apply for grants from organizations such as the (extremely well-funded) Islamic Development Bank. However, these education grants are limited to students practicing Islam.

In addition, if Muslim students cannot get any scholarships, they are encouraged to simply delay entry into university instead of taking on loans. This means qualified Muslim students often put off higher education until they’re in a position to afford to pay for it outright. Given that even public colleges in the US now average over $10,000 per year, this isn’t a viable approach.

So why haven’t Islamic financial institutions stepped up to meet the demand with Sharia-compliant loans?

Well, it’s not as simple as you’d think. Remember, Islamic loans are joint ventures between banks and borrowers. Financing an education is different from financing a home; there is no underlying “asset” here. The banks would essentially need to subjectively quantify career paths based on a cost-benefit analysis. Yikes.

There is a movement in the UK to provide halal loans for Muslim students. Some universities offer inflation-based loans, where students are responsible for paying back the “original” loan with an equivalent inflationary value (right now — bad deal). Naturally, there is some debate on whether inflation-based loans are considered riba.

Conclusion

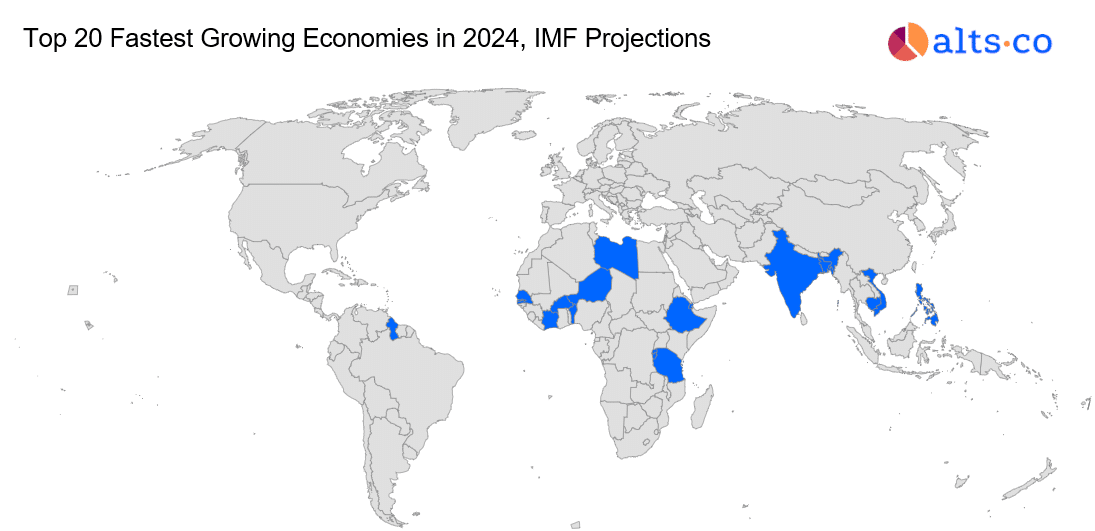

Over the past 50 years, Islamic finance has taken off to meet the needs of a more complex, globalized economy. The industry is growing rapidly today (experts expect 10-12% growth over the next 3 years) and is definitely one to pay attention to.

Islamic finance has always existed for the Muslim community, where money is treated as a medium of exchange, not a commodity. But new financial products have been created to meet the needs of investors steadfast in following the Quran.

I’m torn on some aspects of Islamic finance. Derivatives & excessive risk-taking brought down the global economy in 2008, and rent-to-buy innovations in America mostly seem to work in favor of Blackrock. But I’m not sure if removing interest from the equation solves anything here.

Arguably, Islamic finance’s most compelling features (a focus on charity, and creating wealth through joint ownership agreements) have resonated outside the Islamic community. For better or worse, many perceive current systems as broken, and are increasingly seeking new financial ideas that provide an alternative. Crypto is a perfect example.

But I do think it’s noteworthy that some features of Islamic finance are quite similar to the ones crypto & DeFi promised to bring to the world — and of this writing many of crypto’s promises are rapidly falling apart. I certainly don’t think crypto is down for the count, but it’s interesting that some tenets of the world’s newest financial system have already been baked into the world’s oldest…

Anyways, there’s no question that Islamic finance still has plenty of room for innovation and improvement. Finance has changed a great deal since the Quran, and has in some ways struggled to deal with an increasingly complex financial world.

However, its primary function has always been to comply with the word of God in all financial transactions.

I’m not saying Islamic Finance has all the answers. Far from it! But if we’re going to improve the systems we have, it’s important to understand how other systems work — especially one that dates back as far as Islamic finance.