Today we’re analyzing the complex world of music royalties.

We’ve looked at the basics of this market before. But today, we’re going into valuation analysis — understanding what drives returns, and how to price this stuff.

As a case study, we’ll analyze The Sterling Catalogue: An actual offering from ANote Music.

Details matter in this asset class. We’ll clear it up for you.

Let’s go 👇

Note: This free issue is sponsored by our friends at ANote Music, a European music royalties platform. International investors are welcome, but unfortunately Americans are unable to invest at this time. Regardless of where you live, you’ll find this issue informative and fair.

Table of Contents

Taking the emotion out

Music royalties have always been an asset class with a distinct emotional appeal.

If you’re a die-hard fan of an artist or band, the mere chance of acquiring a slice of their royalties may be all you need to pull the trigger.

But as music investing starts to mature beyond its origins as a niche market, it’s becoming clear that, emotion aside, the financial performance of these assets can be strong enough to justify investment on its own terms.

How ANote Music works

Founded in 2018, ANote is a Luxembourg-based company on a mission to become the global marketplace for music royalty investing.

For this asset class to grow, investors are going to need to see strong performance.

What stands out with ANote is their focus on the financial results of their offerings.

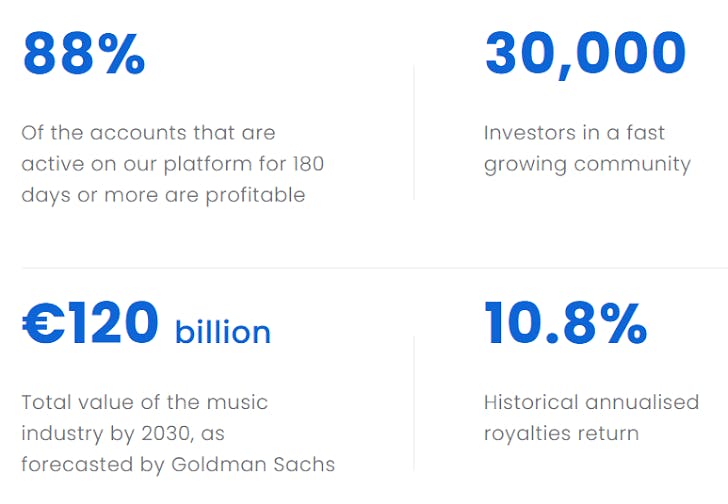

- To date, ANote has registered historical annualized yields of 10.8%

- 88% of accounts that have been on the platform for at least 180 days are profitable

ANote only lists royalty catalogues (we’ll stick with the European spelling today) with a 3-5 year track record of at least €10,000 in annual revenue.

This helps ensure the offerings aren’t too speculative for serious investors.

ANote open to almost anyone, with a min investment of about €5. (Right now they’re offering Alts readers a welcome bonus of €25 cash back on your first €250 investment with code WELCOMEVIP)

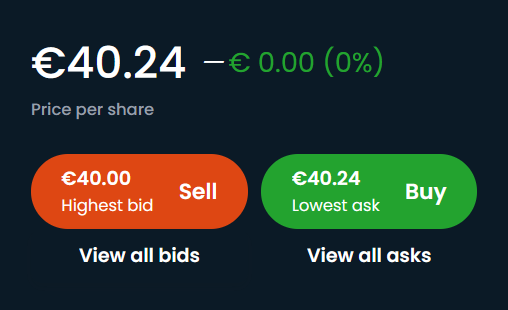

Additionally, ANote has developed a dual market structure, designed to facilitate fair valuations and ample liquidity.

The Dutch Auction model

ANote’s primary market (the market in which royalty shares are listed for the first time) has an innovative structure to balance the clashing incentives often found in alternative markets.

Sellers (artists and royalty holders) want to achieve a high sale price. But too high a sale price means that some shares might get left unsold.

Buyers (royalty investors) want to pay a low price. But if they don’t pay enough, they might not get all the shares they actually want to buy.

ANote navigates this with a Dutch Auction model (so European!)

Here’s how it works:

- Sellers set a minimum price at which they’d be willing to sell their shares.

- Buyers enter bids over a multi-day period, indicating the price and size at which they’d invest.

- Once the biding is over, the lowest price at which all shares would be sold is chosen.

- All buyers who bid equal to or over the selected price pay this new price for their shares.

This structure helps balance the seller’s desire to raise sufficient funds with the buyers’ desire for a fair price.

The Secondary Market

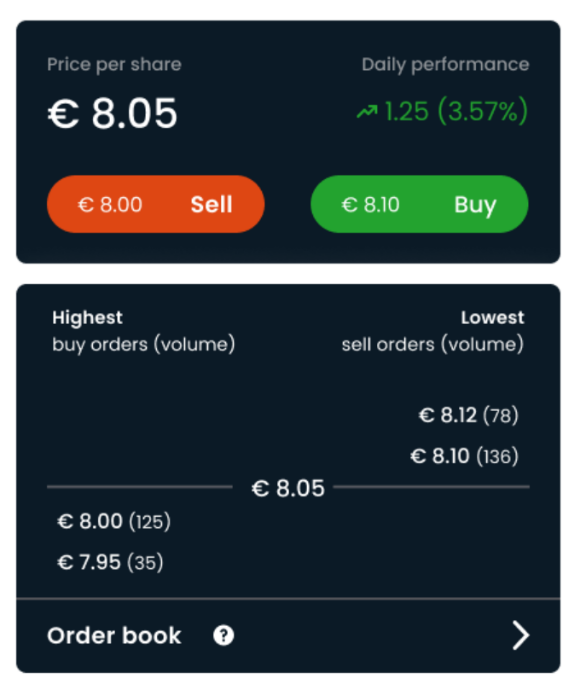

After royalty catalogues list on the primary market, they begin trading on ANote’s secondary market.

After the Dutch Auction ends, trading activity from buyers and sellers determines the market price.

So far, this approach has been successfully used to list catalogues with a total value of more than €5m, including a collection of royalties from US songwriter Brandon Lowry – better known as Sterling Fox.

Let’s take a look.

The Sterling Fox Catalogue

Sterling Fox is sort of a “behind the scenes” music producer.

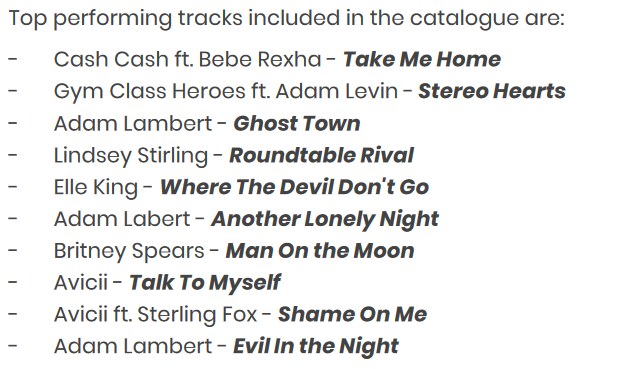

Even if you don’t know the name Sterling Fox, you’ve certainly heard the names of some of the people he’s written for, including Britney Spears, Avicii, and Adam Levine.

The Sterling Fox Catalogue on ANote consists of 100% of the international (ex-USA) songwriting royalties for over 300 songs written by Sterling Fox.

Since the catalogue’s listing on ANote in Sep 2022, it’s distributed a total of more than €75,000 in royalties, with annual returns over that time period averaging more than 10% (on an IRR basis).

Those numbers are impressive, and highlight the potential for outperformance in music royalty investing.

Still, strong performance is far from guaranteed. In particular, overpaying or a package of music royalties can easily lead to poor returns.

So, let’s assume we’re a clear-eyed thinker who only cares about the numbers, not the emotional appeal.

How do we go about valuing a music royalty investment to make sure we’re paying the right price?

The details matter in royalty investing

Before we dive into the numbers, we need to establish exactly what type of royalty we’re looking at.

This is a detail-heavy asset class, where even similar-looking investments can differ materially. So understanding the finer points is key to navigating the market.

Ultimately, royalties derive from copyright ownership (if you need a refresher on the difference between copyrights, trademarks, and patents, check out our recent issue on intellectual property).

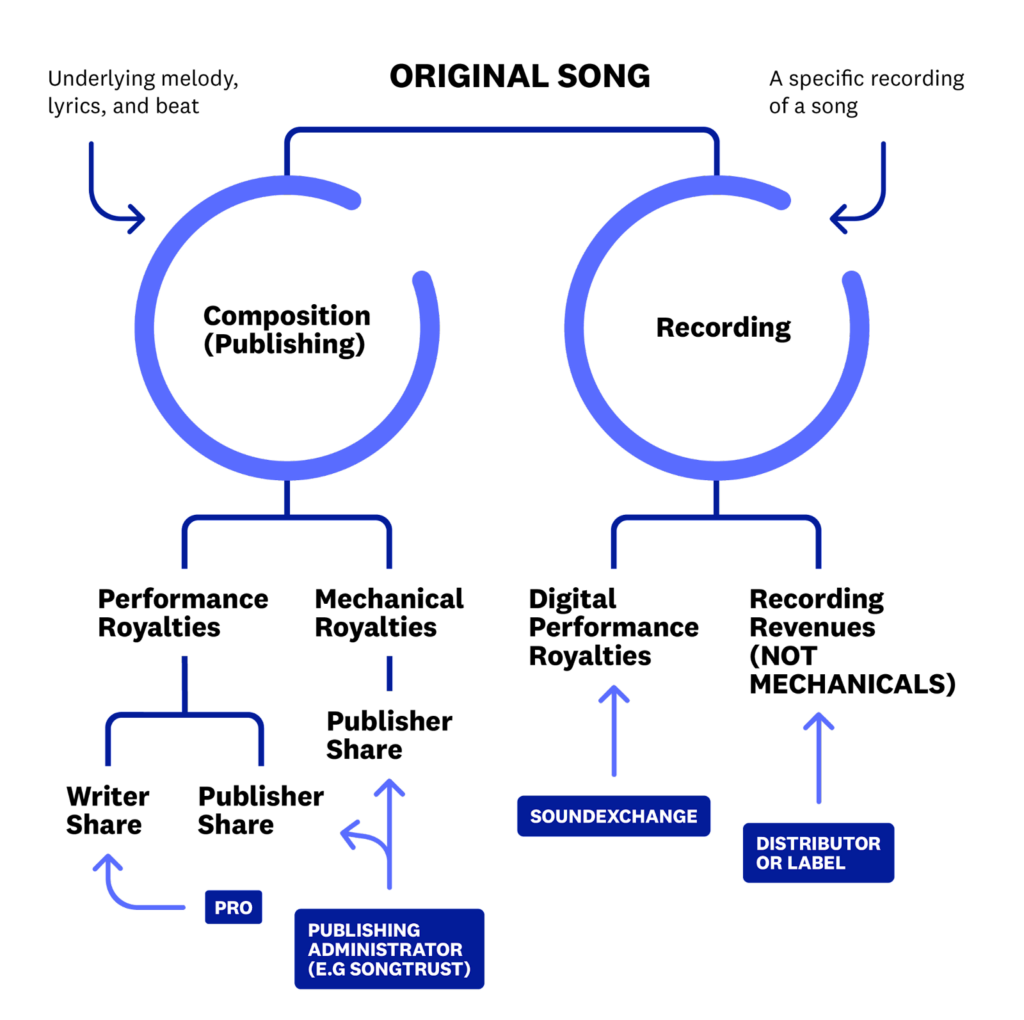

Music royalties get complicated because songs are generally covered by two separate kinds of copyright:

- Master Rights determine ownership of the specific sound of the recording. This is usually whatever party paid for its production — typically a label or recording studio.

- Publishing Rights determine ownership of the underlying musical composition (i.e., chords, melodies, lyrics). This is usually held by musicians.

Since the two copyrights can be held by different parties, each party has a claim to certain royalty streams from the same song.

Mechanical = reproduction (streaming) 💿

Publishing rights holders (songwriters and artists) earn mechanical royalties whenever a song is “reproduced.” This includes physical copies, digital mp3s, and streaming service. (Radio stations are not included.)

Performance = live songs played in public 🎤

Similarly, publishing rights can entitle you to a certain amount of performance royalties.

A “performance” occurs when a song is played in public, like on the radio, in a restaurant, or, curiously, on a streaming service (yep, double-dipping with mechanical royalties).

Sync = movies and TV 🎬

Finally, publishing rights holders can also earn from sync royalties – generated when music is used in “synchronization” with visual content (stuff like movies, shows, and commercials.)

So yes, that’s three different royalty streams. But it’s not all sunshine for musicians.

Publishing-related royalties are typically split with a publishing company as well (commonly referred to as the “publisher’s share.”)

What about the master rights holders?

They can earn sync and performance royalties as well, but never mechanical ones. (if you’re researching this topic in-depth, expect to run into some esoteric legal concepts like neighboring rights).

Not only that, but each royalty type can have unique income characteristics.

Sync royalties, for instance, can be volatile, owing to the fact that these deals are often negotiated on a 1:1 basis for a fixed fee. Streaming-related royalties tend to be a bit more stable.

Certain royalties can even result in unexpected sources of income – like the money owed to mechanical royalty-holders if an artist samples their work.

Here’s the bottom line: you can’t just look at the streaming performance of a song, add up the revenue from movie sync deals, and assume that investing entitles you to all that money.

It’s critical to understand:

- What type of royalty you’re investing in

- What copyright form those royalties derive from, and

- What other parties are entitled to the revenue stream

How long is the royalty term?

Once you’ve navigated the complicated topic of royalty stream taxonomy, the next step is to figure out how long that stream lasts.

While it’s true that music copyright (both masters and publishing) in much of the world lasts for the life of the owner plus 70 years (or longer, in the case of corporate ownership), it doesn’t always mean that royalties last as long.

Some royalty deals are for the “life of rights,” but others might be subject to just a 5 or 10-year term.

A limited term limits the resale value of the royalties, meaning income generation will be the central factor in determining returns.

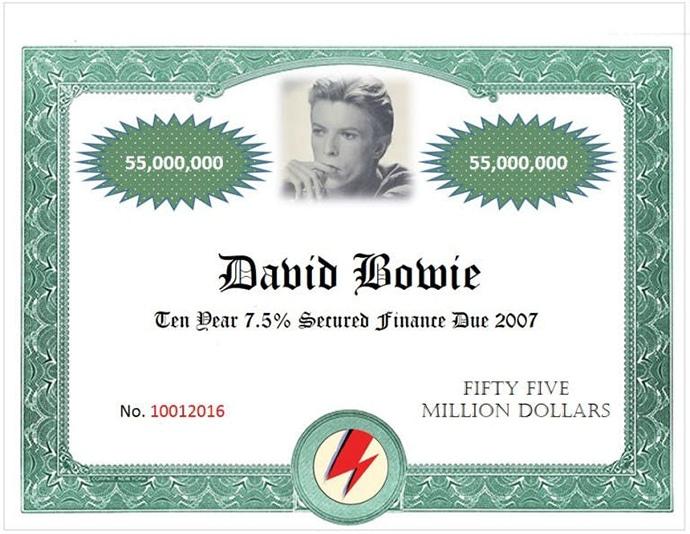

Most famously, the Bowie Bonds that helped launch the whole idea of investing in music royalties had a 10-year maturity during which they were backed by royalties – after that, the bonds were repaid and royalty rights reverted back to Bowie.

How old is the music?

Timing a music royalty investment is a delicate art.

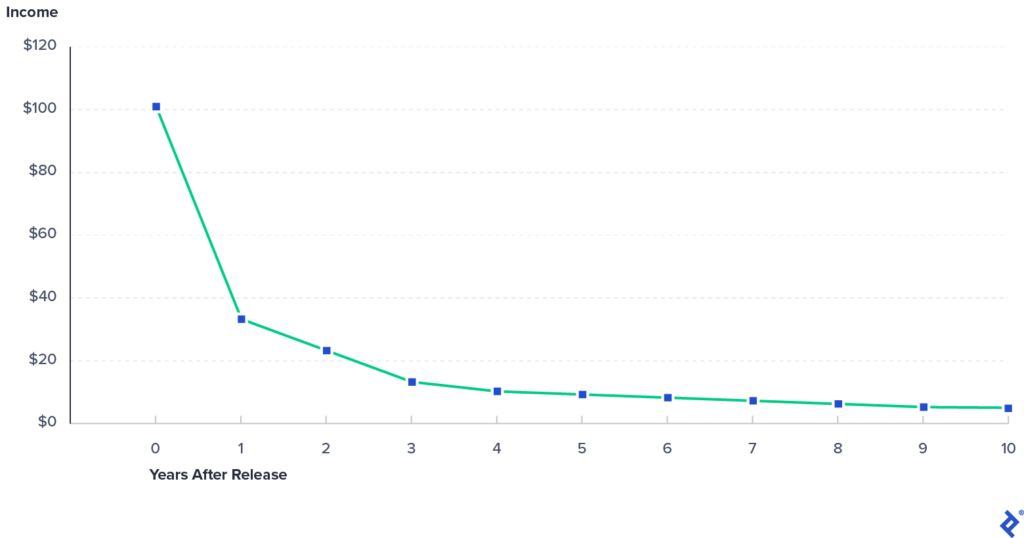

Generally, the first three years are the highest earning years for a song. That makes sense – when a new pop song comes out, it’s all over the radio and fans are constantly streaming it, etc.

But earnings start to fall afterwards. Eventually, around four or five years after release, you’ll see some stabilization.

The benefit to investing in a mature song is that you can get a pretty good idea of how much you’ll earn since you have access to all sorts of historical data.

But while newly-released songs might not have any data to support their popularity, they also bring the greatest growth potential.

The risk-reward dynamics here are pretty similar to equity markets, where investors have to pick between fast-moving startups and slow-growing established players.

Still, the dynamics of the internet mean that even old songs can find their way back into the limelight.

When Netflix used Kate Bush’s 1985 song “Running Up That Hill” in their hit show Stranger Things, it became a global streaming sensation, generating millions of dollars in extra royalties.

Valuing the Sterling Fox Catalogue

It’s time to get into the nitty-gritty – How to come up with a realistic valuation for a potential royalty investment.

Discounted cash flow analysis: The main tool

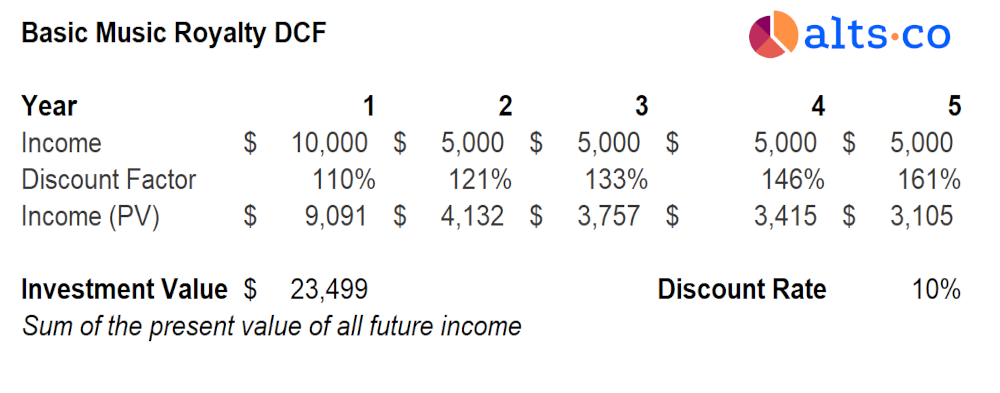

The classic valuation approach you’ll find all over the industry is the discounted cash flow analysis (DCF).

The basic idea is to treat an investment as nothing more than a stream of future income payments.

Since a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow (due to the possibility of earning interest), we’ll need to discount all that income to its present value.

Which discount rate to use is a work of art. Riskier projects calling for a higher rate. Let’s assume a discount rate of 10%.

Discount your income, add it all up, and you get an estimate of what that investment should be worth right now.

For instance, let’s say we’re thinking about investing in a royalty deal with a five-year life that’s nearing stabilization.

In year one, we expect an income of $10k, followed by $5k for each of the four years after that. Since the royalty term will expire, we don’t expect to be able to resell our investment.

If we think the song has a decent chance of being a flop, we need a higher rate of return to induce us to invest.

Supposing we increase our discount rate to 15%, we get a new value of $21,109.

Now, using the DCF approach for music royalty investing requires some caution:

- For new songs, limited historical financials can make it exceedingly difficult to accurately predict popularity and income stream. (Again this is why ANote only lists catalogues with a 3-5 year track record of earning revenue)

- If you’re not an industry insider, you’ll need to try and forecast streaming figures and understand royalty splits in an industry that’s not always transparent.

- Finally, DCF analyses can be sensitive to their exit value if you plan on eventually liquidating the investment. Accurately predicting resale value years in advance, of course, isn’t easy.

With that said, the DCF approach can certainly be powerful, especially if you have some historical data to work with.

Let’s see how this approach pairs with the Sterling Fox Catalogue.

Applying the DCF to Sterling Fox

As we’d expect, when the songs were new, the Sterling Fox catalogue generated a higher income of around €60k/year.

These days, royalties appear to be closer to €30-40k/year.

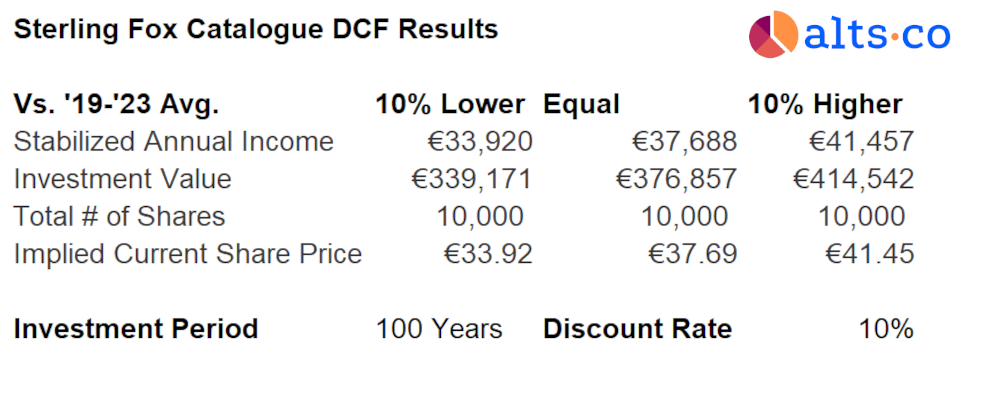

To conduct our DCF analysis, let’s scale up 2023’s incomplete earnings to a full year, by adding the average of the last three quarters and drop years 2016-2018 as a “pre-stabilization” period.

(Of course, there’s always discretion when making decisions like this, so feel free to adjust this analysis to suit your preferences).

Since this is a “life of rights” catalogue, we have to make a decision over the holding period.

To mimic holding this asset perpetually, we’ll calculate our DCF up to a 100-year period. After 100 years, a discount rate makes future income inconsequential.

For a basic analysis, let’s average our 2019-2023 stabilization period earnings, which comes out to €37,688

We’ll also incorporate two other situations, in which earnings are 10% higher than expected and 10% lower.

Here’s what the numbers come out to with a 10% discount rate:

How does this stack up to the current trading price? Surprisingly close! It’s about €40/share at the time of this writing.

Of course, this analysis can be extended and improved in a number of ways.

But here are some preliminary conclusions:

- Even if we expect long-term income to be in line with the 10% higher figure, we still might not have enough margin of safety to invest.

- However, if we adjust to an 8% discount rate, the current price actually looks pretty good (about €7 undervalued at the middle range) – so it depends on our risk perception.

- True long-term stabilization for music may not be super-realistic – this analysis could be redone assuming that income gradually falls to zero over a multi-decade period, with no resale value.

Remember, if you want to invest in the Sterling Fox Catalogue or any of ANote’s other offerings, I’d advise you move quickly and take advantage of their limited time welcome offer: €25 cash back on your first €250 investment with code WELCOMEVIP.

Invest in the Sterling Fox Catalogue →

Disclosures from Alts

- This issue was sponsored by ANote Music

- The ALTS 1 Fund holds no interest in any companies mentioned in this issue.

- This issue contains no affiliate links

This issue is a sponsored deep dive, meaning Alts has been paid to write an independent analysis of ANote and their associated markets. ANote has agreed to offer an unconstrained look at its business, offerings, and operations. ANote is also a sponsor of Alts, but our research is neutral and unbiased. This should not be considered financial, legal, tax, or investment advice, but rather an independent analysis to help readers make their own investment decisions. All opinions expressed here are ours, and ours alone. We hope you find it informative and fair.