Today we’re looking at the intersection of film financing and crypto.

Note: This is Part 1 in our film financing series. You can read Part 2 on film and broadway financing here.

This issue is coupled with an extra-special podcast with award-winning actor, director, writer, and producer Anthony Hayes. Anthony’s latest feature film, Gold, featuring Zac Efron, is out now on Netflix and major streaming platforms.

In addition to acting in nearly 100 films, Anthony is the creator of RETROGRESSION, an innovative new crypto project that aims to disrupt the film financing industry.

This was a terrific podcast, have a watch! 👇

Could this mark the beginning of the end of financial dependence on studios? And how the hell have studios gotten away with shady practices for so long?

Let’s find out 🎬

Table of Contents

Why film financing is broken

Financing a movie is a hell of a task. The average feature-length film employs 550 people, including crew, staff, and actors. For blockbusters like Iron Man, it can be as high as 3,000.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed. And payroll is just the beginning of the expenses.

But the biggest issue is Hollywood’s financial model, which notoriously favors the studios over the actors and directors. This trickle-down economic model means it’s shockingly difficult to actually make money.

For every $1.00 a film makes at a cinema:

- $0.60 goes to the cinema chain (!)

- $0.20 goes to the distributor

- $0.07 goes to the sales agent

This leaves just $0.13 left for everything else. After studios recoup their costs (marketing, travel, SAG residuals), the investors get paid out. There’s often nothing left over to pay the actual filmmaker.

That’s right: Creators are the last to get financial rewards from a film.

This payment injustice isn’t limited to the directors — actors are also affected.

Take Return of the Jedi. The film grossed $450 million in 1983 ($1.3 billion today). But actor David Prowse, who played Darth Vader, never received a single residual paycheck for his work.

The system also favors men over women. In a famous example, Mark Wahlberg once made $1.5 million for a 10-day reshoot of All The Money, while his co-star Michelle Williams, who did the exact same amount of work, earned less than $1,000

Studios and shell corporations

Once studios have eaten, there’s often no pie left. Here’s why:

- Film studios create a separate corporation for each movie they produce. This corporation has a single focus: make the film.

- The corporation doesn’t have revenues, only funding (usually equity or loans) and costs.

- The corporation is set up to appear as if the movie is acting independently of the studios, paying the studio for advertisements, marketing, salaries, and distribution fees. After production you should be left with the funding, the cost of the film/tv production, and an empty bank account.

- However, the corporation essentially acts as shell that works on behalf of the studios and not the film itself.

This setup means a movie grossing hundreds of millions can look like it lost hundreds of millions. The result is a tax write-off of losses both when a movie loses money, and when it’s profitable!

The “Return of the Jedi corporation” couldn’t pay Prowse any residuals because the studio had already taken all the revenue in distribution fees.

In a nutshell, these movies corporations are set up to lose money, because that means the studios make money.

Yeah, it’s bad.

That’s not to say any of this is necessarily illegal. But the market is flat-out rigged against creatives, who in many cases never see a dime in royalty payments.

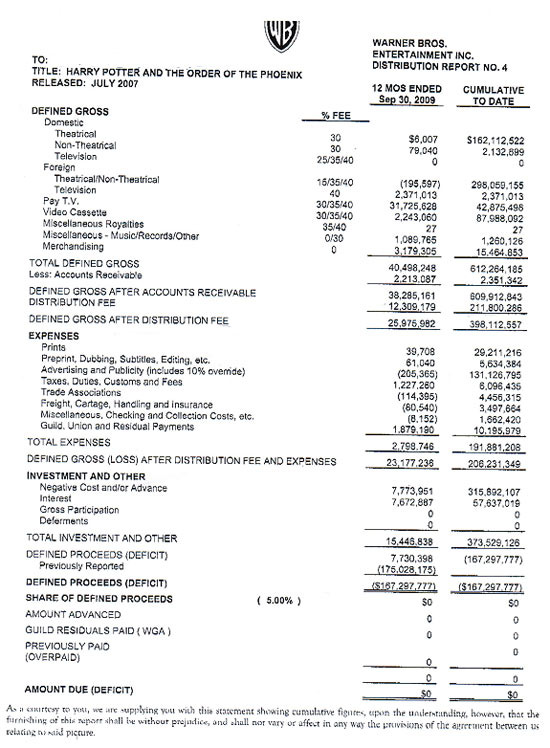

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is another example of this. The film grossed $612 million in the first month after its release, yet Warner Bros Stuios reported a $167 million loss on the film.

What kind of fuzzy math do you need to create a loss from $612 million in sales?

The P&L sheds some light:

On paper, Harry Potter was the worst investment ever. In reality, it was a golden goose.

So, where does all the money go?

Intermediaries and middlemen

Revenue flows through a long line of distributors, sales agents, and financiers that all take a cut of profits in the waterfall, often leaving nothing for the creatives.

Yes, for mega movies like Harry Potter, the lead actors make a good deal of cash. By the final installment of HP, Daniel Radcliffe was paid $25 million.

But here’s the thing — actually tracking down if they get residual checks is really difficult. There are no definitive answers on what kind of royalties the actors get, and if they do, how much.

To avoid this, TV stars have gone from being exploited during cable programming’s heyday, to demanding royalties be written into their contracts. Cast members from Friends, Seinfeld, and Everybody Loves Raymond now make millions each year on royalties.

For older shows like I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island, and The Brady Bunch, the cast never saw a single residual check.

How Netflix removed the middlemen

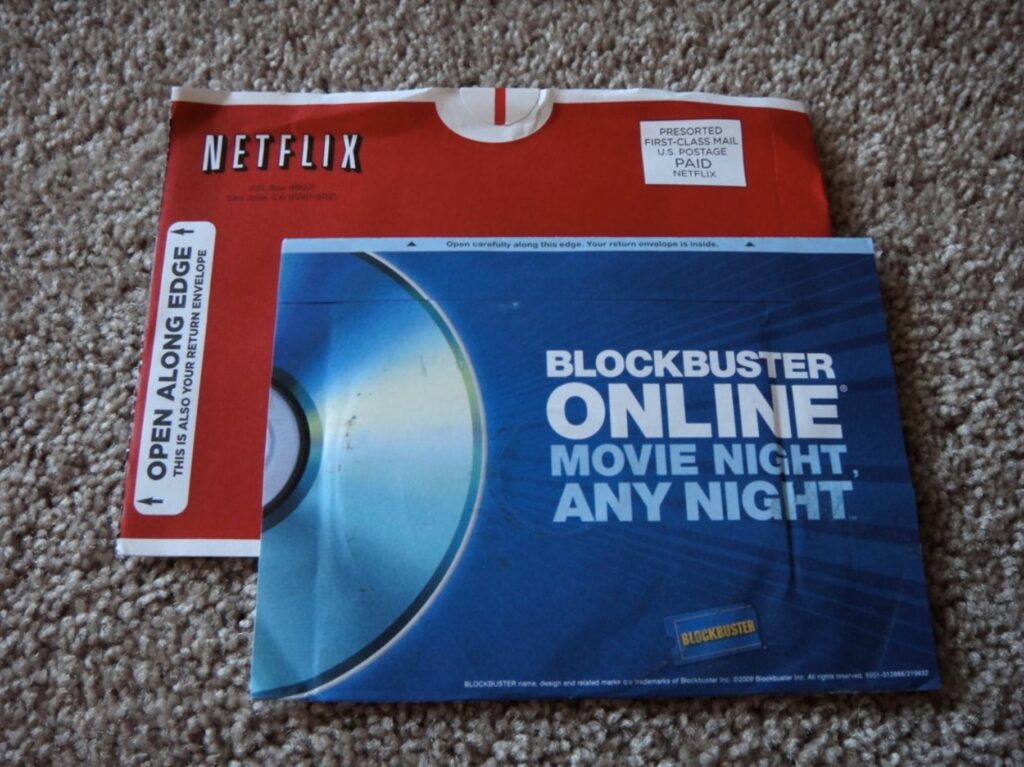

Back in 2005, Netflix’s biggest competitor was Blockbuster.

Before becoming a streaming giant, Netflix upended the video rental model by mailing customers DVDs with a prepaid return envelope.

Blockbuster countered with its own DVD-by-mail service (and did a pretty good job!) But they never stopped playing catch-up. By that time, Netflix was well on its way to developing its flagship revolutionary online streaming service. As Netflix grew, so did its content offerings, which helped usher in a Golden Age for television.

In 2013, the company opened up Netflix Studios on the heels of its first original release, Lilyhammer. The next year, House of Cards became the second Netflix original, gaining critical acclaim and forcing all major studios to take notice.

Nowadays, Netflix produces more than 150 original series, feature films, and documentaries every year. They regularly receive Oscar and Emmy Award nominations for top projects, and have a global network of studios from Albuquerque to Singapore. Most importantly, Netflix changed the way films are financed.

Before Netflix, studios performed creative accounting, ensuring they took profits to the chagrin of everyone else.

Netflix, on the other hand, works directly with producers. When Netflix buys the rights to a film, they pay the full cost of production, as well as pay producers a healthy premium (sort of like a book advance.)

The Netflix approach is great because:

- Filmmakers get a handsome advance and a guaranteed profit

- The system directly rewards filmmakers and investors

- It eliminates the need for expensive intermediaries

But it’s still not a perfect system because Netflix owns the IP.

You read that right. Netflix owns the future rights to every film they produce. All of it.

This means no matter how much money a film makes throughout its lifetime, the directors, actors, and investors get a one-time single payout. It’s like a book advance or record deal without any future royalties. Not great.

So the system still needs improvement. And that’s where crypto can help.

DeFilms: A new protocol

Recently, a new kind of film project has emerged – the decentralized film (also called a DeFilm). One leading project is Retrogression.

Retrogression’s founder is Anthony Hayes, who co-wrote, produced, directed, and acted in the movie Gold, starring Zac Efron.

Gold is a killer movie. It’s a tale of greed in a lonely, tense, windswept, post-apocalyptic landscape. It’s an empty-feeling movie; with just a few characters and very little dialogue. But that’s what makes it so great. Every word counts.

I cannot recommend it highly enough.

In many ways, Gold was the culmination of Hayes’s ambition to make a film true to his vision, free from the constraints of middlemen and studio red tape.

But Hayes wanted more, and he’s now turning to the blockchain to fund Retrogression. Think of it as a movie and entertainment franchise.

How did Retrogression get started?

Retrogression is Hayes’s creative vision of a dystopian future. It’s also his reaction to film studios that have historically maintained control of intellectual property by writing creatives out of future revenue streams.

Five years ago, Hayes was in the middle of one of the most exciting projects of his career. He had written a script for a crime drama titled Stingray, which he was also set to direct and act in. He assembled a cast that included Joel Edgerton, Jon Bernthal, and Maggie Gyllenhaal.

But when Stingray was weeks away from filming, the financial backers decided to pull the plug. (Which happens all the time) The studio conglomerate wasn’t satisfied with the financial projections, and the film collapsed instantly. Hayes called the experience “devastating.”

Who better to strike back at the studio model and create an alternative than someone like Hayes?

What exactly is Retrogression?

Retrogression is a film and blockchain project financed with the RTGN token. Its pre-sale launch earlier this year raised 200 ETH ($560k at today’s rate), with 90% of it put into the RTGN liquidity pool on Uniswap. Ownership of the token represents a stake in the entire Retrogression franchise.

The Retrogression ecosystem is packed with utility:

- The film, which will be produced as a trilogy of films

- A play-to-earn game in the Retrogression metaverse

- A streaming platform for indie filmmakers called The Film Crib, where both creators and fans earn $RTGN

About the film

Retrogression takes place 300 years into the future in a world devastated by global flooding. An elitist group establishes a world order, rewarding higher amounts of RTGN to people with a lower carbon footprint.

Retrogression is being developed, from the script, on the blockchain. As Anthony Hayes says, The creative things aside, which I love, the fire in my belly is about putting the power and the fiscal returns back into the hands of the creatives.

About the play-to-earn game

The Retrogression play-to-earn game is built on the Enjin blockchain for its metaverse. The video game will explore scenes from the movie, provide opportunities to earn RTGN, and collect valuable NFTs that unlock different video game levels.

The Retrogression universe comes to life by incorporating RTGN from the movie. This turns it into an actual token with utility and allows gamers to earn RTGN by playing in the metaverse.

Why Retrogression built on the blockchain

So if film financing is broken, why use crypto to solve it?

Similar to NFT music, for film creatives, crypto represents a terrific vehicle for crowdfunding projects, managing royalties, and rewarding fans. By raising money through a token, the Retrogression model further eliminates middlemen participants who stand between creator and audience.

Unlike traditional studios where profits trickle down, or even Netflix, where royalty payments are non-existent, Retrogression’s financial model allows creators to be first in the waterfall. It also reduces financing fees, elevates profit participants along the way, and continues to create revenue for the film.

Sure, Hollywood has “percentage points,” which give individuals a percentage of a film’s gross income. But again, it often comes after everyone else is paid. Smart contracts can be programmed to provide residual income for life.

Conclusion

In Gold, Zac Efron’s character is abandoned in the desert, guarding an enormous gold nugget while hoping the stranger he discovered it with (played by Hayes) returns with an excavator so they can dig it up. The desert takes its toll, with Efron’s face and lips blistered by the unrelenting sun and heat.

But Hayes recalls in disbelief how one sales agent interested in financing the film insisted that Efron appear clean-shaven. The investment never came, and those conditions from agents send creatives like Hayes into a tizzy.

Retrogression aims to disrupt business as usual, and Hayes welcomes his new role as “enemy of the studio.” By eliminating the studios from the equation and utilizing community members as investors, there are fewer hands in the jar along the way.

The waterfall is streamlined, and investors and creatives are first in line for recoupment, making it easier to finance a film and generate returns for those who bring the creativity.

In fact, where Retrogression has led, others are now following. MovieCoin allows coin holders to invest in several projects on its platform. The coin gives the holder perpetual profits from the film. It also allows creators to build a community that is given a voice to upvote certain projects and provide suggestions for future productions — a main ethos of Web3.

Hats off to Anthony Hayes for creating an entirely new filmmaking protocol.

This could truly be the start of something special.