Today we’re exploring translation technology.

With over 7,000 languages worldwide, overcoming the language barrier is one of the oldest problems in human history.

For decades, English has been the world’s “glue,” providing the foundation for trade, tourism, and science.

But now that translation technology is getting scarily good, will this affect English’s role as the global lingua franca?

Let’s go 👇

Note: Most of this issue is free, but to read the end you’ll need the All-Access Pass 🎟️

Table of Contents

Solving the language barrier

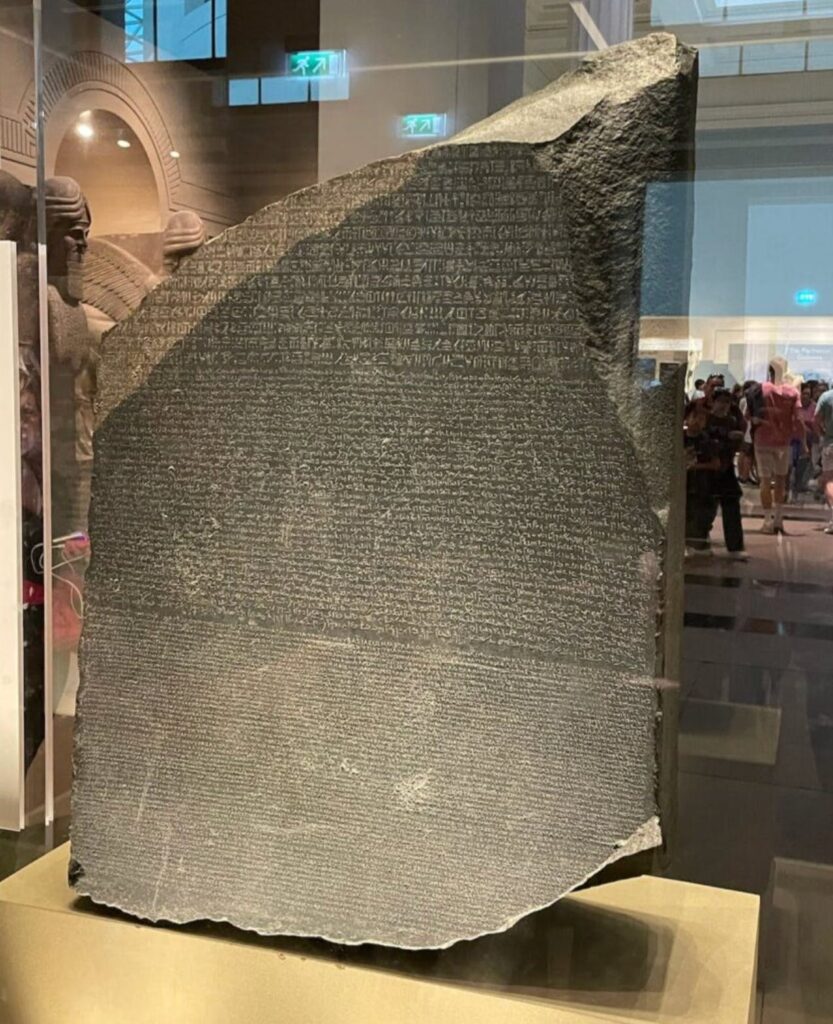

Language barriers have been a problem since writing was invented 5,400 years ago.

Logically, there are only two ways to overcome a language barrier:

- Get all parties to use a common tongue (even if it’s not their primary one), or

- Have everything translated

Translation used to be labor-intensive and costly. It just wasn’t practical for most people. So establishing common languages became the best way to break through the barrier.

But now we have some astounding recent developments in translation technology. So this dynamic may be starting to change.

And if it does, the implications for the future of language and communication are profound.

To understand how language barriers might be overcome in the future, let’s start with how they’ve been overcome in the recent past — through English.

How English became the world’s language

The world has settled on English as the common language.

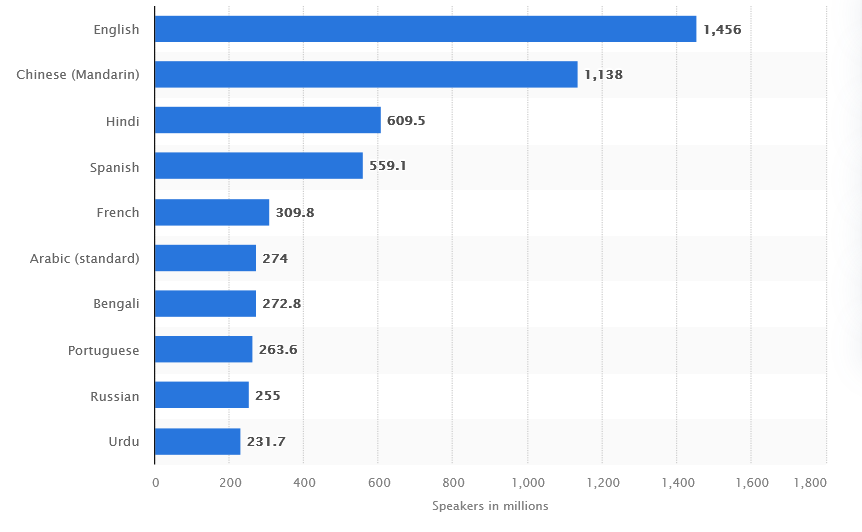

It’s the most popular language in the world, with 300 million more speakers than the next runner-up, Mandarin.

The vast majority of English speakers learn it as a second language.

English has just 400k native speakers (well behind Mandarin or Spanish) — implying that over a billion non-native speakers have learned it.

English’s dominance is best exemplified by the fact that the European Union Commission operates in English – even though Britain left in 2020, and English is only the official language in two relatively small member states (Ireland and Malta).

And English’s reach spreads far beyond government. It’s the global standard for both international business and technological innovation:

- Business: Multinational companies have basically all adopted English as their official inter-company language, regardless of where they’re based. Examples include Nokia (Finland), Airbus (France), and Samsung (Korea).

- Science: Every one of the world’s 100 most influential scientific journals is published in English. Non-English papers have significantly lower citation rates.

- Air travel: English is literally the language of the skies. It’s the official language of international air traffic control.

- Programming: The world’s most common programming languages are all English-based. (Though there are exceptions)

So how did English become the global standard?

Network effects

The value of learning a language is strongly impacted by the number of people who already speak it.

This is the economic idea of agglomeration, or network effects. It constantly pops up: Social media companies, venture capital, ski resorts, etc.

Whichever language has a slight head start in total use can quickly snowball into a global standard.

English got its head start with the rise of the British Empire, which at its peak in 1921 ruled over nearly a quarter of the world (in both land area and population).

Languages in the same family are easier to learn

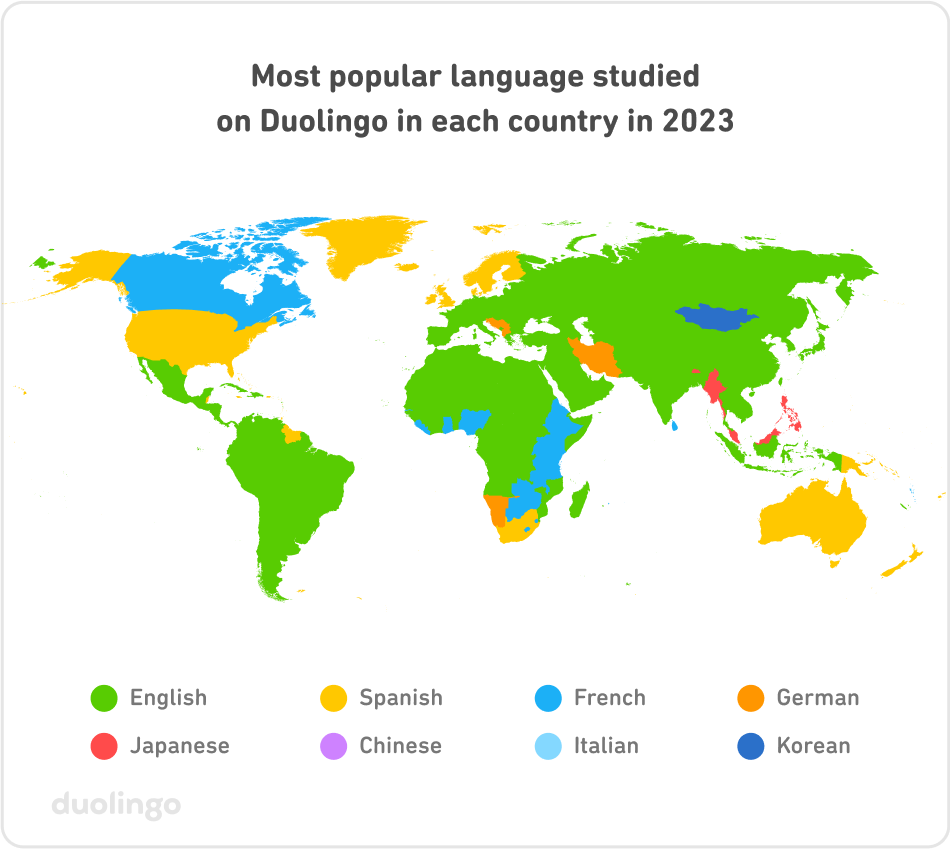

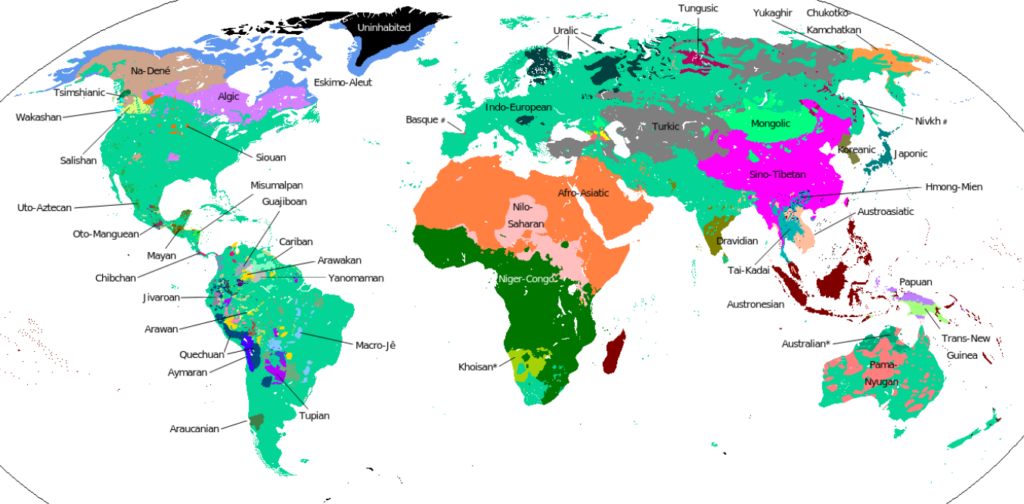

One underrated fact about English is that it’s an Indo-European language.

Languages in the same family tend to have similar alphabets and structures, making them easier to learn as a secondary language. Today, about half the world speaks a language in this Indo-European family.

This is why Mandarin is unlikely to replace English as a global language. As a member of the Sino-Tibetan language family, Mandarin is fundamentally harder for Indo-European speakers to learn.

But there is one area where English is less dominant than you might expect — media.

Is English’s grip on media weakening?

English is considered the language of the internet. But in reality, the online world is actually pretty multilingual.

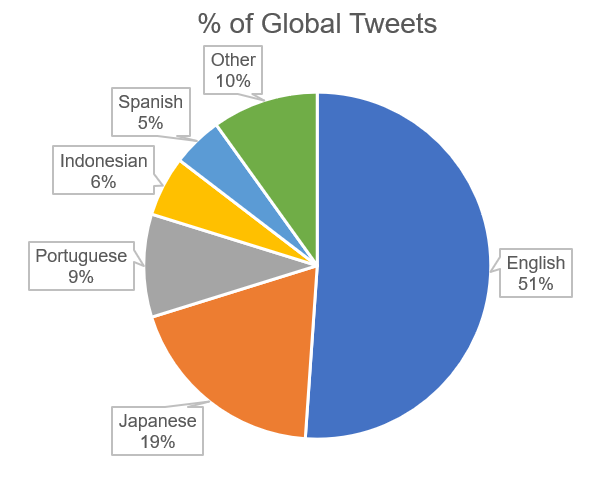

Studies of the top languages on Twitter find that only half of tweets are in English. A plurality, sure. But not exactly total dominance.

Moreover, foreign-language media has been having something of a renaissance in recent years, including:

- Films and shows like Money Heist and Parasite,

- Musical artists like Bad Bunny and BTS.

- Anime is now reaching a more mainstream audience through apps like Crunchyroll.

It’s an economic solution because it’s dominant in practical areas like coding, research, and communicating with foreign travelers. But it’s less dominant in cultural domains.

In fact, culture is becoming tailored for a global audience, undermining the old assumption that international consumers must adapt to English:

The rise of moviegoers in China has created an incentive for Hollywood to make movies that appeal to Chinese audiences as well as Western ones… You get a lot of movies…which dominated the Chinese box office but barely registered in the US. -Conor Sen, Bloomberg (2018)

English’s dominance is mostly about economics

To get things done, the world needs to overcome language barriers.

We need a tool, and English is simply the most cost-effective tool to do so.

But here’s the thing — if English is really nothing more than a cost-effective solution to overcome language barriers, it’s liable to be replaced by an even better solution.

And in recent years, one viable alternative to global English domination has emerged: universal translation technology.

A quick history of machine translation

Machine translation has been around for a while, but it’s only recently that computers have been able to translate anywhere close to human level.

The ultimate goal is a universal translator, a device commonly found in sci-fi that allows instantaneous communication across any language barrier.

How far has machine translation come, and how far is there left to go?

The ‘rules-based’ approach

One of the earliest attempts at machine translation was done by SYSTRAN, founded in California in 1968.

In another example of how America’s national security industry launched Silicon Valley, SYSTRAN’s earliest customer was the US military, who wanted to translate Russian documents.

SYSTRAN was an early innovator of the rules-based approach to machine translation.

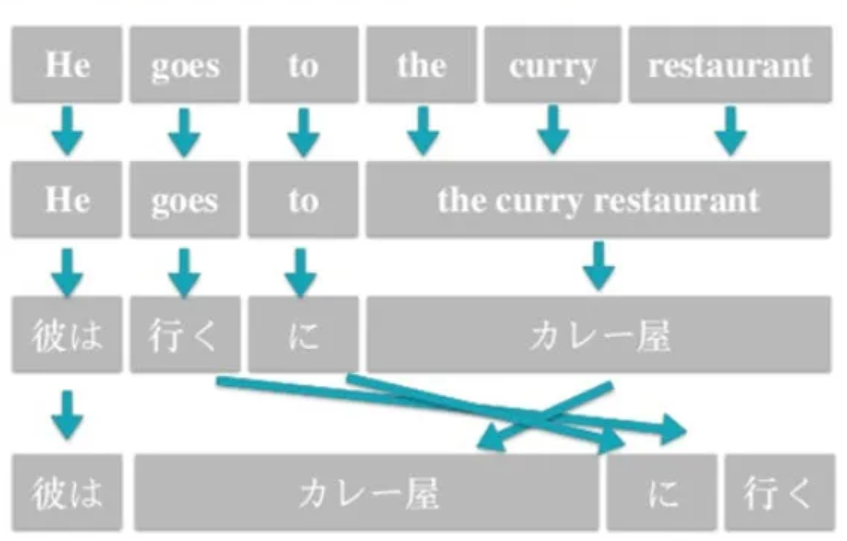

It’s a three-step process:

- Deconstruct the sentence into individual words (and their role in the sentence)

- Translate each word into the target language, one by one

- Reconstruct the sentence using the rules of the target language

Sounds good in theory, right?

Unfortunately language is too messy for this rules-based approach to work well.

- First, words can have multiple definitions. “Book” can translate to libro or reservar in Spanish, depending on the context.

- Second, rules-based systems struggle with ambiguity that doesn’t align with the rules of a language (which is often the case with speaking transcriptions).

Rules-based approach was considered cutting-edge until someone realized that translation is less about linguistics, and more about statistics.

Statistical Machine Translation (SMT)

The ideas behind statistical machine translation (SMT) were known as far back as the 50s, but it wasn’t until IBM started experimenting with stats in the 80s that people began taking the approach seriously.

Statistical approaches are more contextual than rules-based ones, working to understand context and phrases.

As the name implies, these translations are based on statistical probabilities, with likelihoods generated by learning from underlying data sets.

Despite some drawbacks, SMT is very powerful. For years, this was the technology powering Google Translate.

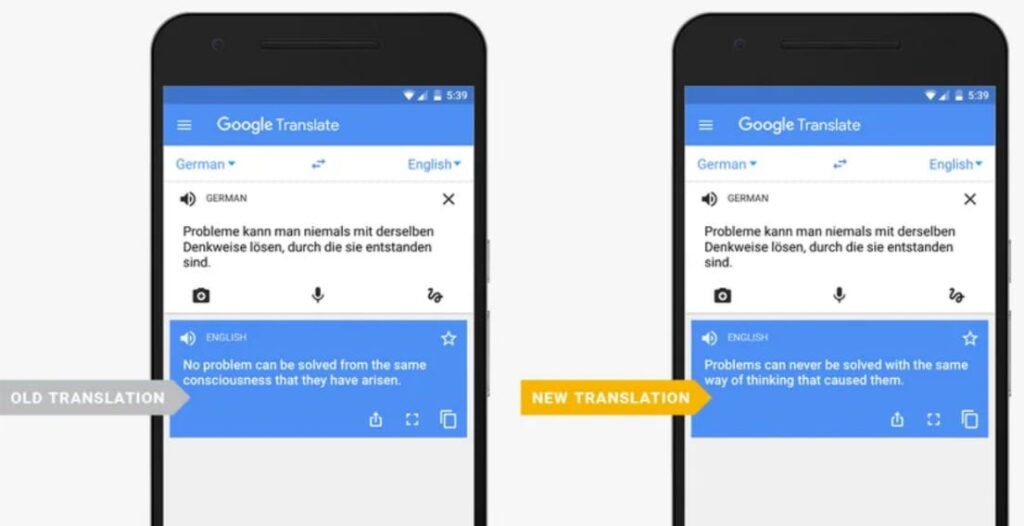

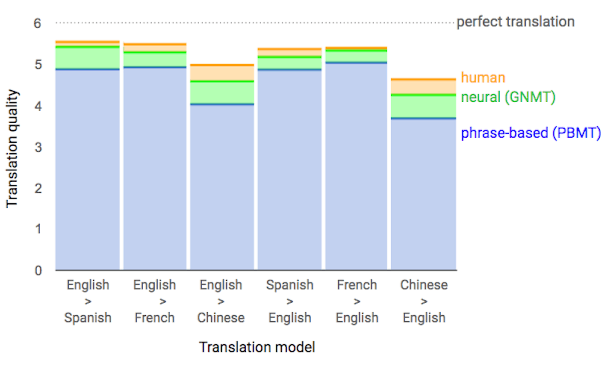

But in 2016, Google swapped statistical models for an even better approach: neural machine translation.

The modern standard: Neural machine translation (NMT)

In translation, context is everything.

Just as SMT started translating phrases instead of words, NMT started translating not just phrases, but entire sentences.

NMT models have come closer to matching human performance in translation than any other technology.

NMT models have also opened the door to a fascinating new capability: being able to translate between language pairs, for which the model has no bilingual training data! (This is called zero-shot translation).

Google’s old SMT model had an ”intermediary” translation to English. But this seriously hampered its accuracy, and NMT models don’t need it.

Here’s how zero-shot translation works:

- An NMT model learns to translate between a primary pair with plenty of data (like Korean to English).

- The model also learns to translate between a secondary pair, (like English to Japanese).

- Having fine-tuned its parameters, the model can spontaneously translate between Korean and Japanese — despite never having seen any Korean-to-Japanese translation.

Similarly, NMTs have enabled the possibility of doing direct speech-to-speech translation, without first having to transcribe audio into text.

Google and Meta have both successfully experimented with this approach, which could help retain non-linguistic aspects of conversations (like timing, pauses, and laughter) during real-time translations.

The future of translation

English has historically been used as a common language to overcome language barriers.

But now, translation technology is finally good enough to be a cost-effective replacement for English.

So, what does this mean for English? What does the future of translation look like? And what companies are building that future?

The most exciting translation companies

Unsurprisingly, Big Tech is still the biggest player in translation, with Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta all boasting expansive research in the space.

But here are some startups around the world to pay attention to: